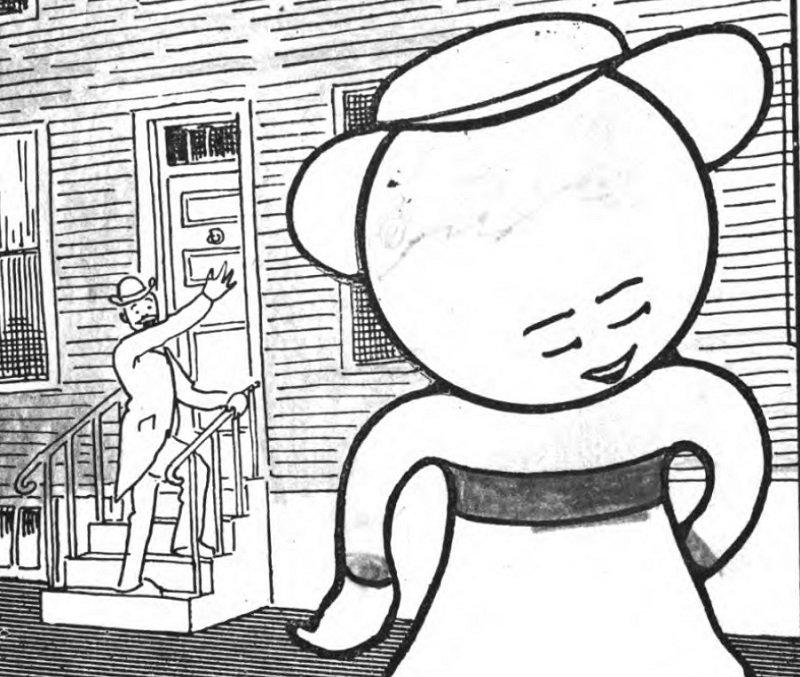

Long before actress Gwyneth Paltrow adopted the word to market personal care products, “Goops” were the creation of writer and artist Gelett Burgess (1866–1951). The peculiar circular-headed hairless creatures first appeared in the late 1890s in his Lark Journal, an avant-garde magazine that mixed humor and original typography. The goops’ creator became so famous for the poem, “The Purple Cow,” published in the first issue, that people frequently recited it to him, so he penned a sequel threatening in rhyme to kill whoever quoted it.

Burgess was also the originator of the ungainly word, “blurb.” “Goops,” or the “muse of nonsense,” stemmed from Burgess’s absurdist aesthetic. He wrote that, “The artist must first know the anatomy of the human figure to the minutest detail. The Goop is the result of carefully excluding every effect of this knowledge

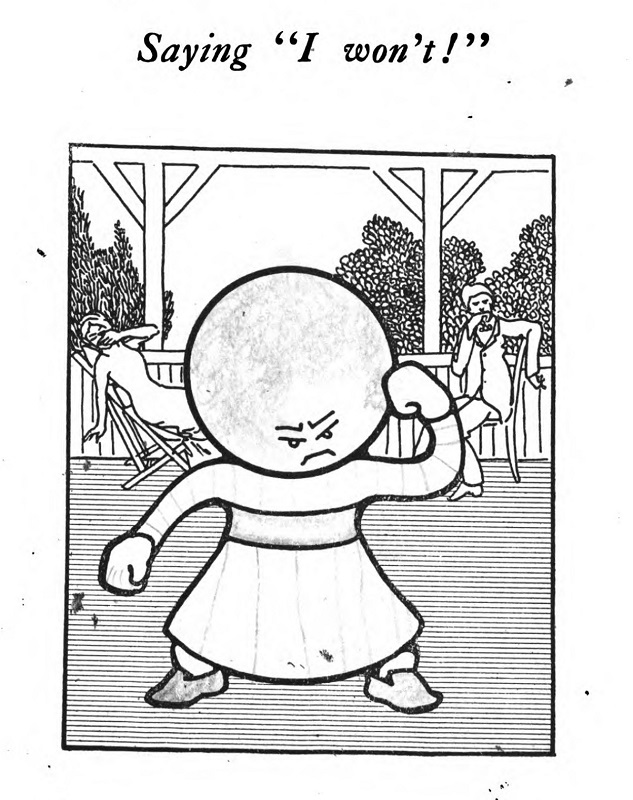

“I won’t!” says young Amelia Pratt;

“I won’t do this!” “I won’t do that!”

Now isn’t “won’t” the naughtiest word

That anyone has ever heard?

Now isn’t that the rudest way

A Goop could answer? I should say!

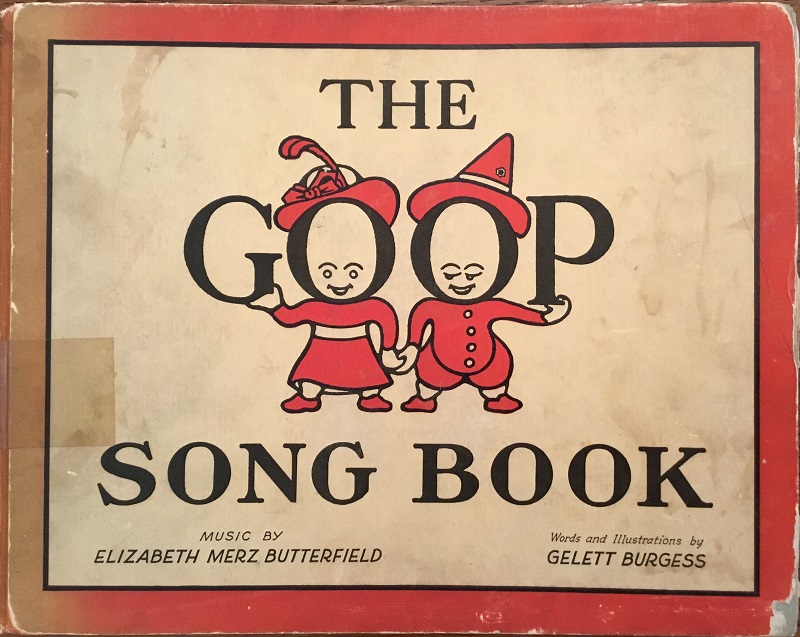

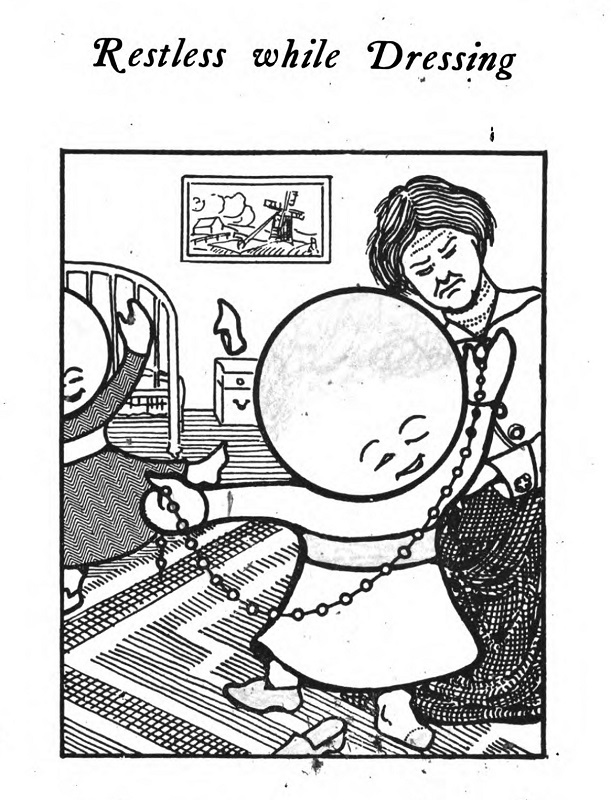

Viewed as a means to teach children good behavior by presenting its opposite, Burgess’s creations came to pay the bills, and he published numerous goops books in the first half of the twentieth century. Composer Elizabeth Merz Butterfield (1896–1947) may have read them as a child or shared them with her own offspring. She started composing by writing “whimsical little songs” for her four children. The ten songs in her Goop Song Book are based on poems from Burgess’s The Goop Directory of Juvenile Offenders Famous for Their Misdeeds and Serving as a Salutary Example for All Virtuous Children (1913). They were dedicated to her son Jimmy, who inspired her to set them to music, though he may have grown up by the time they were published in 1941.

Butterfield spent much of her musical life in women’s circles, and so like many other women composers, she is largely unknown. In 1924 she joined the National League of American Pen Women, an organization that included professional female composers. Butterfield also became a charter member of the Pen Women’s spinoff, the short-lived Society of American Women Composers, which boasted Amy Beach as its first president. In the 1930s Butterfield joined forces with soprano Myrtle Lindbeck to perform her songs, and the two appeared before women’s clubs and civic groups for many years. Butterfield’s “Home” won the Pen Women’s 1934 song contest, receiving the prize of its publication by Clayton F. Summy. “Home” was also performed at a Pen Women’s concert held for First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt at the White House.

Butterfield’s output included theatrical and choral music and chamber works, presumably for her sister, a Juilliard-trained violinist, though only her songs were published. For much of her life, Butterfield lived in Jamestown, New York. She had a long time association with the nearby Chautauqua Institution, where she helped organize events for other women composers. In the summer of 1934, Butterfield took composition lessons there from the vacationing Arnold Schoenberg.

Butterfield, whose sentimental and patriotic songs were her most frequently performed works, seems like an unlikely composer for the ironic Goop stories. Yet she was known for her interest in art for children, and her children’s songs were reviewed in the Music Educator’s Journal. One of Butterfield’s song books was translated into Japanese and used in Japanese schools. For two years after Butterfield’s death at age 51, the Chautauqua Society she founded after she moved to the Washington, DC, area awarded a “Butterfield Prize” to the resident Chautauqua composer who produced the best music for children’s voices.

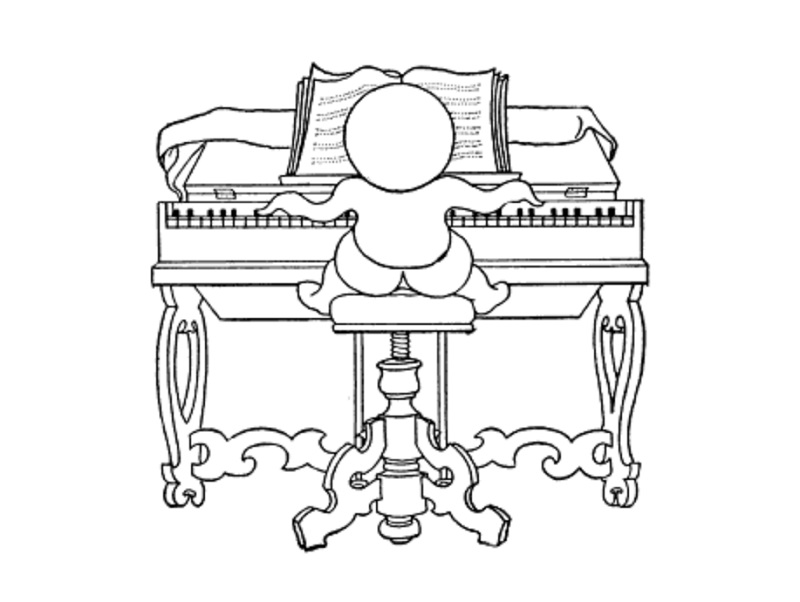

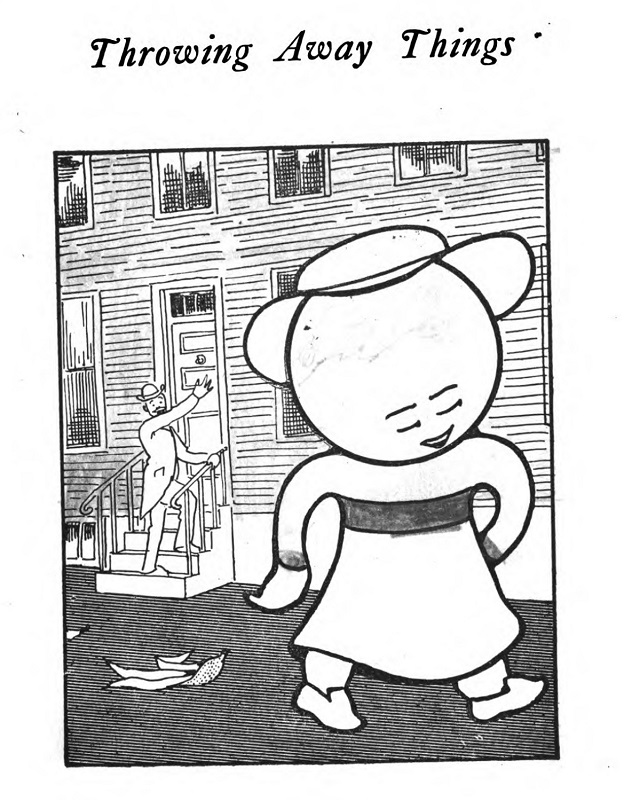

Published alongside the corresponding poem and image from The Goop Directory, Butterfield’s goop songs open with brief introductions and feature uncomplicated piano accompaniments. Like Burgess’s black and white line drawings, the music’s largely diatonic simplicity somewhat belies the wayward character of the creatures it depicts. Yet Butterfield provides subtle hints of musical rebelliousness. For example, when she set the poem for rude Amelia Pratt, the crucial word “won’t!” leaps emphatically to a higher note far above the main melody. The tune for Uriah Stead, who procrastinates going to bed, seems unable to act, stuck on just two or three notes over chromatically descending chords in the bass. For the poem about Midget and Bridget Hopper, who fidget while being dressed, the melody in both voice and piano restlessly hops down the notes of the triad and then bounds an octave up. The mock seriousness of “Nancy Beal,” who discards her banana peels in front of people’s doorsteps, climaxes with an unexpected fortissimo diminished chord to express the horror at her “shocking trick.”

Perhaps the children for whom Butterfield’s songs were intended would have missed the of humor her musical depictions of Burgess’s goops, but reviewer Lilla Belle Pitts found that her tunes “fit them to perfection.”

Notes

Evans, Brad. “Gelett Burgess and the Flight from Reality.” In Ephemeral Bibelots: How an International Fad Buried American Modernism

Kappel, Elisabeth. “Elizabeth Merz Butterfield.” In Arnold Schönbergs Schülerinnen – biographisch-musikalische Studien, 574–80. Stuttgart: J.B. Metzler, 2019.

“Mrs. Butterfield, Talented Composer, Dies at Buffalo.” Jamestown (N.Y.) Post-Journal (April 8, 1947).

Pitts, Lilla Belle. “Piano and Song Books.” Music Educator’s Journal 28, no. 4 (Feb. 1942): 44.

Stein, Sadie. “Disgusting Lives.” The Paris Review, March 11, 2014.

Wenke, John. “Gelett Burgess (30 January 1866–18 September 1951).” In American Humorists, 1800–1950, 68–76. Ed. S. Trachtenberg. Dictionary of Literary Biography, vol. 11. Detroit: Gale Research, 1982.

Wilson Kimber, Marian. “Women Composers at the White House: The National League of American Pen Women and Phyllis Fergus’s Advocacy for Women in American Music.” Journal of the Society for American Music 12, no. 4 (2018): 477–507.

Illustrations:

Goop playing piano is from Gelett Burgess, Goops and How to Be Them: A Manual of Manners for Polite Infants Inculcating Many Juvenile Virtues Both by Precept and Example, with Ninety Drawings (1900).

The 3 pictures of individual goops are from:

The Goop Directory of Juvenile Offenders Famous for Their Misdeeds and Serving as a Salutary Example for All Virtuous Children (1913).

Photo of Elizabeth Merz Butterfield, from Find a Grave, accessed 15 Jan. 2022, memorial page for Elizabeth Langworthy “Betty” Merz Butterfield (22 Jan. 1896 – 7 April 1947), Find a Grave Memorial ID 68662941, Chautauqua Cemetery, Chautauqua, NY; maintained by LeAnn Childs (contributor 47029761).