Clara Schumann’s songs offer rich territory for thinking about how she put her stamp on the genre at a pivotal point in its development. What individuates her approach, and what it means to study and perform her songs, are questions that Joe Davies (JD), Harald Krebs (HK), Stephen Rodgers (SR), Susan Wollenberg (SW), and Susan Youens (SY), contributors to the recently published essay collection Clara Schumann Studies

Entering the Expressive Worlds of Schumann’s Songs

JD: From your experience of teaching, performing, and writing about Schumann’s songs, what aspects of her approach do you find most fascinating?

SY: One aspect of her expressivity that I find especially enchanting is her use of gesture; her music seems to model the very emotion she seeks to make resound in our minds and ears. For example, at the beginning of “Sie liebten

HK: As my chapter in CSS makes clear, I am excited about Schumann’s approach to declamation. My analysis of declamation in “Sie liebten sich beide” (the song that Susan Youens mentions above), with performance illustrations, is available here (starting at 7:52). I am also particularly impressed by her expressive harmonic language. Steve’s work on cadence highlights one important aspect of this; another is her distinctive use of dissonance (as in the opening measures of “Volkslied” and “Die stille Lotosblume”).

SR: Schumann’s harmonic language, mentioned by Harald, is something that fascinates me. Her sense of harmonic motion is extraordinary; she knows just when to inject a little dissonance into a phrase, and also when to avoid a strong cadence for expressive effect. I also love the expansiveness of her melodies. They tend to move in four-bar spans, but those spans often connect seamlessly with each other, creating a long-breathed continuity. I just finished a book about her songs (The Songs of Clara Schumann, forthcoming from Cambridge University Press). In it, I write about the breadth of her themes, which I see as a real hallmark of her songwriting style. It’s partly this expansiveness that makes her melodies such a delight to sing – even if it requires real breath control!

Favorites

JD: Of Schumann’s songs, which do you find yourself returning to, and for what reasons?

HK: I enjoy her songs with virtuosic piano parts – “Am Strande,” “Lorelei,” and “Er ist gekommen in Sturm und Regen.” There aren’t so many Lieder by great piano virtuosos in which the latter pull out all the stops and create piano parts that are pianistically demanding while being wonderfully expressive (some of Liszt’s Lieder would be additional examples). The swirling pattern of “Am Strande” is a delight for the fingers, but is also, more importantly, a vivid evocation of a stormy sea. Clara’s “Die Lorelei” immediately throws us into an “Erlkönig”-like mood of impending disaster, instead of dwelling on the vague sadness mentioned in the first stanza–a unique approach. The rising sixteenth-note “gusts” in “Er ist gekommen” so effectively conjure up the meteorological and emotional storms. The change to a gentler (and technically easier) accompaniment pattern in the final section perfectly corresponds to the change in season and state of mind.

Here is a performance of “

Another favorite of mine – of the more contemplative kind – is “Der Mond kommt still gegangen,” whose finesse of declamation is particularly impressive (as I describe in my chapter in CSS).

SR: “Der Mond kommt still gegangen” is also a favorite of mine; it’s the perfect example of Schumann’s ability to write music that looks straightforward at first glance (the song isn’t terribly chromatic, and it moves in the same regular, four-bar chunks I mentioned earlier) but is nonetheless full of subtlety and expressive force.

Those two things – subtlety and force – might seem like opposites, but so often it’s the smallest details in her songs that bring me to my knees. “Der Mond kommt still gegangen” has some great examples, like the chromatic chord progression and phrase stretching on the words “Liebchens Haus” (beloved’s house), which Harald discusses so beautifully in his chapter. But those kinds of moments are all over her songs. Take (as just one more example) the final cadence of “Die gute nacht, die ich dir sage,” which gently smudges the boundary between the dominant and tonic chords, creating a sense of haziness and distance that is perfect for this song.

Here is a performance of “Der Mond kommt still gegangen” by Barbara Bonney and Vladimir Ashkenazy:

SY: Schumann’s ability to surprise me with some either softly subtle or proclamatory maneuver was among the first traits I noticed: when I first encountered her songs, I would constantly catch my breath, taken off-guard by something she did. Being a Schubert-lover, I was floored by her homage to “Erlkönig” in her “Lorelei,” with pounding triplets that make the ancestry obvious. How I wish I could have heard her play this! The octave leap at “wildem Weh” is the sung equivalent of a scream of terror – and how brilliant is that! And there is no piano introduction: we are catapulted into panic and fear.

In fact, she makes both beginnings and endings matters to ponder, as my brilliant colleagues on this blog have pointed out in their works. “Die stille Lotosblume” begins with two blurred chords portending – what? At the “close” of the longer piano postlude, we “end” with the second of those chords, a non-resolving dominant harmony – Schumann’s analogue to the question, “O flower, white flower, can you understand [the white swan’s] song?” The poet, symbolized since ancient times by the figure of a swan, encircles the exquisite lotus flower and sings to it, wondering if it can understand. One can hear this several ways: as the Romantic poet serenading the symbol of the Orient with a possible chasm of perception separating the two or, in still larger terms, as the mysteries of Eros and Art given sounding form.

Small spaces / tiny cells

JD: Much of Schumann’s music, particularly her piano miniatures, conveys the sense of “multum in parvo” (much in a small space) – in what ways is this true of her songs?

SY: I will fuse your “multum in parvo” with my amazement at how many song conventions and formal structures she varies in complex ways. One of my current favorite songs is “Auf einem grünen Hügel,” which seems at first bone-simple: the hunting-horn motif symbolic of memory (think “Der Lindenbaum”), the spare texture, the perfect folk-like art song (“im Volkston”). But she complicates the matter by measure 5 with a plangent suspension in the piano’s inner voice and even more by the gasping, off-beat rhythms of measures 7–8 (we stumble in grief). Each of the three stanzas begins with translucent, bleak simplicity and proceeds through gathering complexity to the end, especially the final stanza, with its added last phrase darkened by a Neapolitan sixth (Schumann’s phrasing is masterful).

SW: I didn’t in CSS write on her songs, though I have written on one elsewhere that in all the lively discourse so far has only I think been mentioned by name (as being on a recent recording) – “Liebst du um Schönheit.” And something you said in your introduction, Joe, is pertinent here – about her individual “voice.”

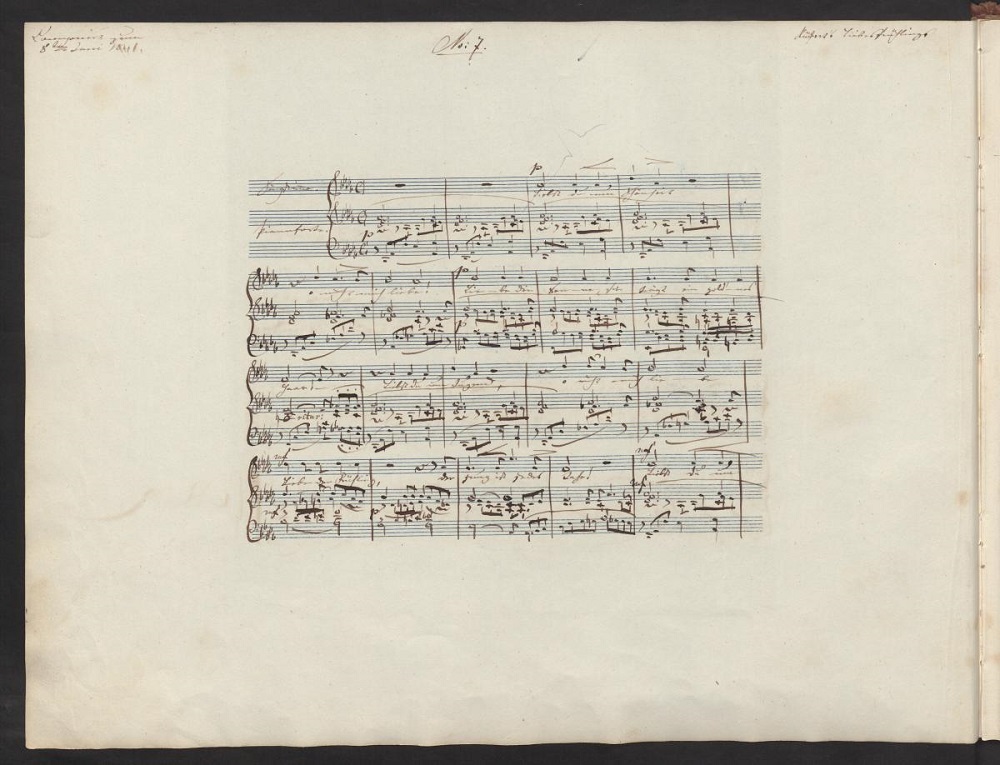

in the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin – PK.

That song – which I find perfect on its own terms – did seem to me to link with her own psychological background – to put it simply, a mixture of uncertainty and confidence. Also, I wrote on Clara and Robert Schumann’s studies of Bach, for CSS, and I think Clara Schumann responded to Bach partly because – and this is seen in “Liebst du um Schönheit,” she too can weave a whole piece from a tiny “cell” – so with utter economy of material, and what you’ve called here “multum in parvo.”

Here is a performance of “Liebst du um Schönheit” by Barbara Bonney and Ashkenazy:

I also respond – at the opposite end of the spectrum from Harald’s liking for virtuoso accompaniment, though he also values the less obviously virtuosic writing too – to her apparent simplicity of expression in a song such as “Liebst du,” and I would agree with Steve that we can find subtlety often of a harmonic kind in such a song. It can be just one chromatic note that introduces a disturbance which may unfold in what follows.

Notes

See an earlier WSF post about Clara.

The autograph

Harald Krebs, “A Way with Words: Expressive Declamation in Clara Schumann’s Songs,” in Clara Schumann Studies, ed. Joe Davies (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2021), 75–94.

Stephen Rodgers, “Softened, Smudged, Erased: Punctuation and Continuity in Clara Schumann’s Lieder,” in Clara Schumann Studies, 57–74.

Susan Wollenberg, “Clara Schumann’s ‘Liebst du um Schönheit’ and the Integrity of a Composer’s Vision,” in Women and the Nineteenth-Century Lied, ed. Aisling Kenny and Wollenberg (Farnham: Ashgate, 2015), 123–39.