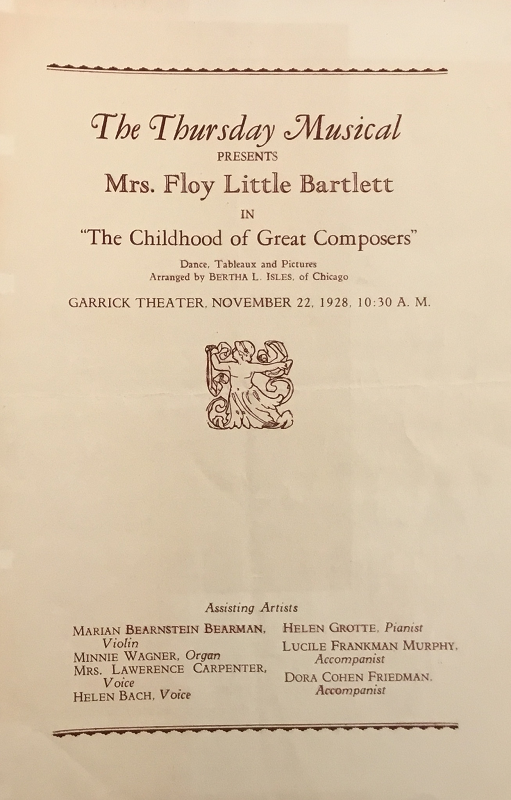

On 22 November 1928, Minneapolis’s Thursday Musical presented the program, “The Childhood of the Great Composers.” The city’s largest women’s music club hosted the event. Called “a new form of entertainment” by the Star Tribune, in order to raise money for its scholarship fund, the concert featured composer Floy Little Bartlett (1883-1956) telling composers’ stories with costumed children playing the composers and other characters. A series of tableaux depicted episodes from four famous lives, including Bach copying music by moonlight and Handel discovered playing music in the attic. Little Mozart was depicted with his violin, and Mendelssohn and his sister Fanny imagined Shakespeare’s fairies. Thursday Musical members performed music by each composer, and the entire event climaxed with child fairies dancing to the Scherzo from Mendelssohn’s music for A Midsummer Night’s Dream.

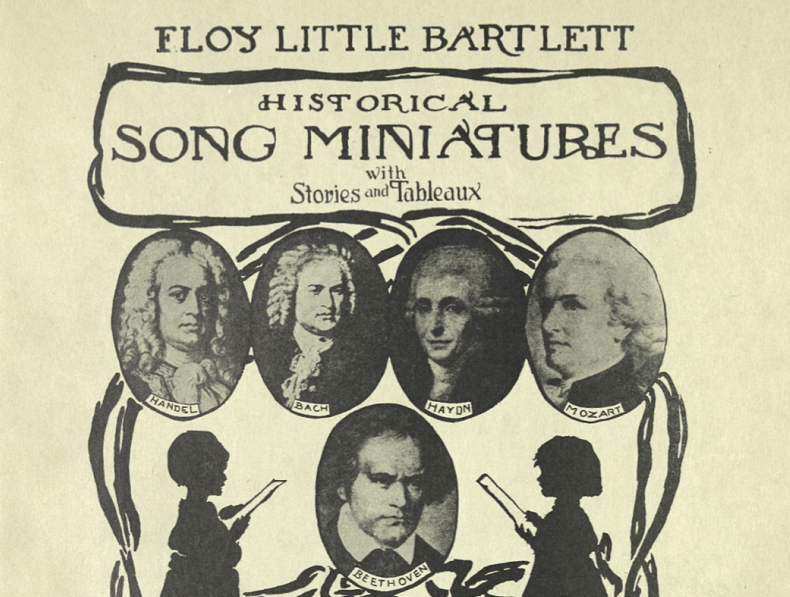

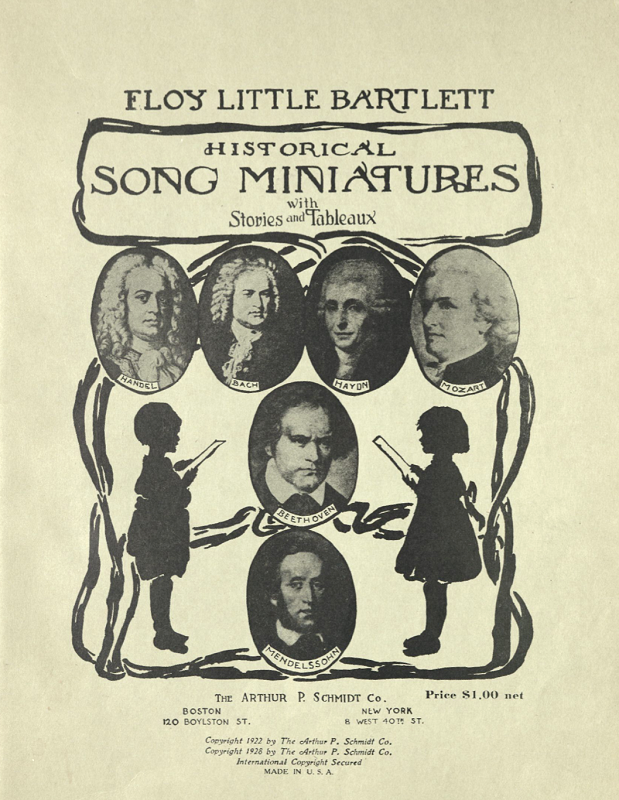

The elaborate spectacle was inspired by Bartlett’s Historical Song Miniatures, stories of the four composers and Haydn and Beethoven told in brief songs based on their music. Scores for Bartlett’s compositions are now difficult to find, but there must still be a few copies in the Twin Cities, as choral conductor Philip Brunelle featured them in his YouTube series in 2021.

Bartlett’s goal of “cultivating a taste for good music in children” was also that of many women’s organizations, which sponsored music appreciation programs and worked to enhance the status of canonic European composers. The General Federation of Women’s Clubs, which helped to promote Bartlett’s music, mounted a campaign against jazz in the early 1920s and organized memory contests for young people to learn melodies by European composers. They hoped to turn young people away from the kind of popular songs that in recent years had become easily available on radio. Although she was a violinist by training, Bartlett primarily produced songs for or about children. In “A Boy’s Philosophy,” a little boy complains about how he dreads winter due to scratchy long underwear. Bartlett’s choral setting of Eugene Field’s popular poem, Wynken, Blinken, and Nod, was sung by two thousand – 2000! – Ocean City school children. Several of Bartlett’s songs were performed by Kitty Cheatham, who, often dressed as an eighteenth-century shepherdess, gave regular Christmas and Easter programs for children in New York City into the 1920s.

Cheatham often provided lyrics for well-known classical melodies, so she may have given Bartlett the idea for songs telling the stories of composers’ lives set to their own music. Bartlett cleverly wove a work by the featured composer into each song, such as Beethoven’s Minuet in G, Mendelssohn’s Nocturne, and “The Heavens are Telling” from Haydn’s The Creation. Her rhymed texts provide the composers’ biographies. Several songs end grimly, if factually, with their composers’ death dates. Mozart, despite his “works beyond compare” died “in Vienna, lonely, poor, and in despair.” Nonetheless, the reviewer for the Musical Courier believed that children would be delighted, finding the set “not only unique in its conception but also decidedly musical and instructive.” Though recognizing Bartlett’s pedagogical intent, a stuffy review of the Thursday Musical’s program found it all too juvenile for the “veterans of our major music society.” In 1932 Philip Page penned a more congenial treatment of Bartlett’s songs for a London newspaper, reprinting several of her lyrics and declaring that “Young America is being brought up in the way it should go.” The amused critic joked that Sir Thomas Beecham should conduct massed choirs in her song about Handel at the next Handel Festival.

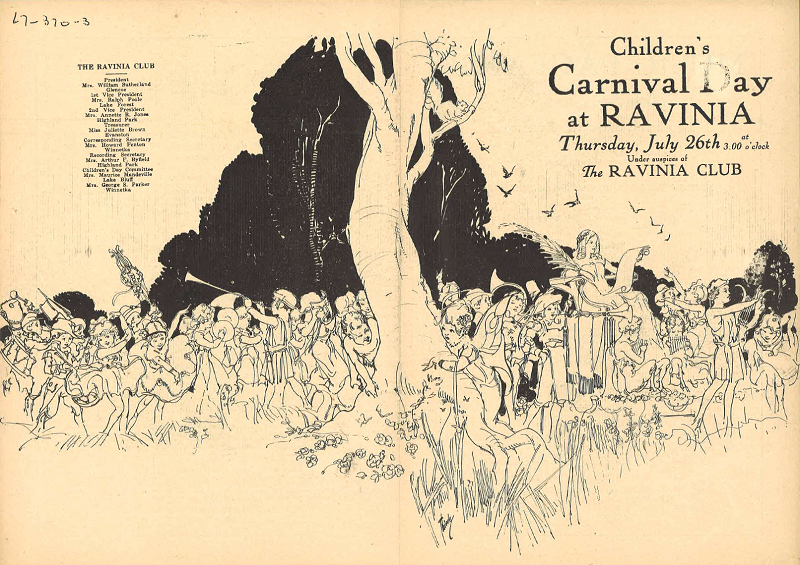

Bartlett’s Historical Miniatures were heard in numerous settings. She presented them to various women’s clubs, according to the Musical Leader, “in the happy manner of one enthusiastic over her work.” One newspaper photo showed her, violin in hand, in a dress from the time of Bach. In 1928, the Nevin Club of Corsicana, Texas, performed Bartlett’s songs at the Carnegie Public Library in a program honoring local “junior musicians.” The children of the Juvenile Fortnightly Musical Club of Springfield, Ohio, also acted out the songs in 1934. The Historical Miniatures were also heard at the Chicago Symphony’s summer concerts held at Ravinia Park in Chicago’s northern suburbs. Bartlett was a member of the women’s auxiliary for these concerts, the Ravinia Club. She served as president of the committee that organized its children’s day, helping to furnish free “educational entertainment” for thousands of children on Thursday afternoons. The suggested tableaux that Bartlett published with the second edition of her songs, intended to be created within a gigantic golden picture frame, were devised by Betha Iles, director of the Academy of Dramatic Education, and were but one of several children’s pageants she arranged for Ravinia.

Despite the performances of her Historical Miniatures, Bartlett came to be better known for The Busy Book (1931), a volume of stories, connect-the-dot pictures, crossword puzzles, and other amusements for children taking car trips or confined to bed during illness. Bartlett marketed her book by supervising children’s games at Marshall Field’s department store in Chicago, and by appearing in a “Busy Time” radio program. Although the Historical Miniatures were mostly forgotten, the General Federation of Women’s Clubs still preserves copies of Bartlett’s songs in their sheet music collection. For several decades they were available for loan to clubs working to enhance the musical knowledge of their communities; they helped in women’s efforts to maintain the European canon as a dominant part of American culture.

Selected Bibliography

Collection on the Thursday Musical, James K. Hosmer Special Collections, Minneapolis Central Library.

Sheet Music Collection, Women’s History and Resource Center, General Federation of Women’s Clubs, Washington, DC.

“Floy Little Bartlett.” In Musical Iowana, 1838-1938: A Century of Music in Iowa, 87-88. [Des Moines]: Iowa Federation of Music Clubs, 1938.

The Musical Leader 43 (23 Feb. 1922): 196.

“New Music.” Musical Courier 85/8 (31 Aug. 1922): 34.

Page, Philip. “Truth for the Young.” The Evening Standard. 24 July 1932.

“Thursday Musical.” Minneapolis Star Tribune. 23 Nov. 1928.