As the Western Canon expands to include more diverse composers that truly reflect the world we live in, previously unpublished works have taken center stage. Perhaps you are familiar with the incomparable Florence Price, whose works have been brought back to life in concert halls around the world. Or maybe you read guest blogger Judy Tsou’s post on the manuscript “Birth,” an unpublished song by American composer Amy Beach. What is it that draws us to unpublished manuscripts? It is natural to ask why composers like Amy Beach chose to not publish certain pieces.

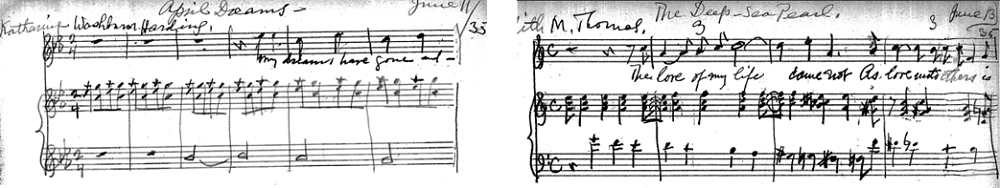

While completing my dissertation on the entire art song corpus of Amy Beach in 2022, I ran into the issue of actually creating the corpus. Multiple lists existed, yet each presented a different total number. I realized that the unpublished songs were causing the discrepancy, and (virtually) visited two archives. The vast majority of manuscripts and diaries are housed at The University of New Hampshire and the University of Missouri at Kansas City. As I looked at all the unpublished songs, two caught my attention: “April Dreams” and “The Deep-Sea Pearl.”

Before I influence your opinion too much, I’d like you to listen to one of Amy Beach’s most popular songs from her Three Browning Songs, “Ah, Love but a Day!,” in a beautiful recording by soprano Kate Royal, with pianist Malcolm Martineau. In comparison, here are MIDI recreations of “April Dreams” and “The Deep-Sea Pearl.” Something is clearly different – there is more crunch, dissonance, angst. Neither of these songs sound like the Amy Beach most of us know and love. But why do they sound so different?

“April Dreams” and “The Deep-Sea Pearl” were composed on 11 and 13 June 1935, respectively. As no other songs were composed around these dates, we can reasonably assume they were meant to be a pair. These dates may hold the key to understanding why they sound so different compared to Beach’s other songs. Almost exactly twenty-five years earlier, on 28 June 1910, Amy Beach’s husband Dr. Henry Harris Aubrey Beach passed away. His death impacted both Amy Beach’s emotional state and her work. Not only did Amy Beach lose her partner as a husband, but she also lost the man who held the control and power in deciding her musical path. He prevented her from performing and touring as a pianist and dictated which compositions deserved her attention. She set multiple songs to his texts and dedicated others to him, and the two often performed her new songs at the end of a day.

The text and music of these two unpublished songs give insight into what Beach may have been experiencing as she approached the 25th anniversary of her husband’s passing. In both songs, there is a common theme of yearning or loss that stands in opposition to what the narrator wants. Musically, the yearning and opposition is represented through tonality and accompaniment patterns. Let’s take a closer look at both songs. As was her practice in the large majority of songs she wrote after the death of her husband, the poems are by women.

APRIL DREAMS

Written by Katherine W. Harding, the text for “April Dreams” describes the yearning feelings of a dream forgotten when one wakes up. Dreams, elusive and ethereal in nature, are constantly out of the grasp of the speaker – they need them to come back. In the second stanza, the wind is described in explicit detail. It kisses crocuses, which can symbolize new beginnings and imply that the speaker’s dreams will return. However, the speaker ends the poem by acknowledging the dreams are so far away, perhaps too far away, and shall not return.

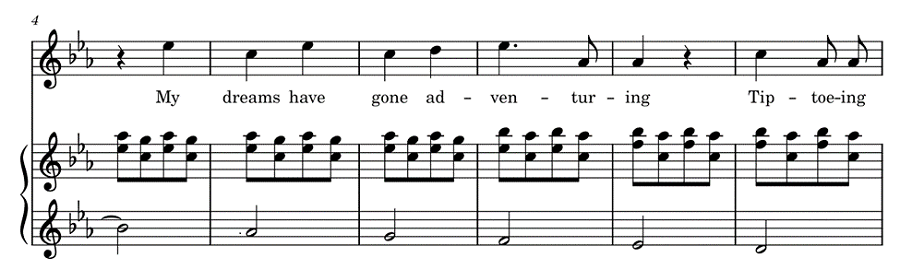

My dreams have gone adventuring

Tip-toeing down the lea

I wish a little April wind

Would blow them back to me.

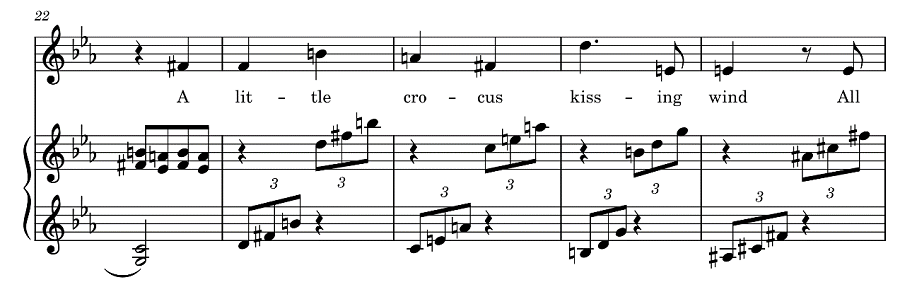

A little crocus kissing wind

All full of fluting song

And scent of drowsy, waking buds

That have been sleeping long.

O wind blow back the wanderers

Wherever they may be

My little dreams adventuring

So far away from me!

Turning our attention to the musical setting, the piano introduction establishes the intangibility of the dreams through tonal ambiguity. Rocking eighth notes in the right hand alternate between fourths and fifths (Eb-Ab, C-G). Separate, they sound hollow and empty; combined, they could form an AbM7 chord or a Cmadd6, both dissonant and yearning for resolution. These rocking notes continue throughout the entire first stanza as a descending bass line begins (and never ends).

In the second stanza, there is a brief moment of hope in the text that is reflected in the music. A new accompaniment pattern emerges as sweeping arpeggios, this time ascending. We hear a glimmer of true tonality with G Major entering, yet it is quickly swept away with chromaticism. Underneath all of this hope, the descending bassline continues; it serves as a reminder that the dreams are far away.

Both accompanimental patterns return in the final stanza, with a single line repeated from the first stanza: the dreams adventuring. This time, however, this line is set to the ascending triplet accompaniment figure. The hopefulness of this ascending figure is ironically placed against the dreams being far away from the narrator. As the song reaches its conclusion, tonal resolution is avoided as there is no clear cadence or satisfying ending to the song. Just as the song lacked resolution musically and poetically, Amy Beach seemingly lacked resolution in regard to her husband’s death.

THE DEEP-SEA PEARL

“The Deep-Sea Pearl,” while not about dreams, presents a more apparent connection to the loss of Dr. Henry Beach. Central to understanding Edith M. Thomas’s poem is the symbol of a pearl, often found hidden in oysters and associated with purity, wisdom, and feminine beauty among other things. Following the opening lines that establish their love as non-conventional, the poem continues in a darker tone: from the pain of a wound grew the pearl, representing the complex balance between love and pain. In the final verse, the narrator states that, no matter what, the pearl will remain sealed and contained at the bottom of the Deep Sea, a treasure forever inaccessible. Emotional conflict is felt throughout the poem as the relationship and its aftermath are both bittersweet for the narrator.

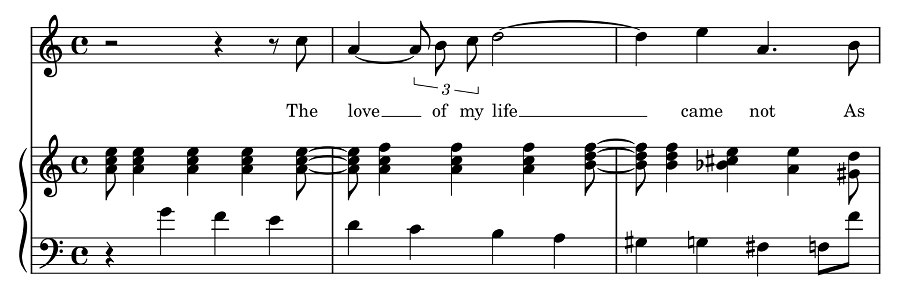

The love of my life came not

As love unto others is cast;

For mine was a secret wound —

But the wound grew a pearl, at last.

The divers may come and go,

The tides, they arise and fall;

The pearl in its shell lies sealed,

And the Deep Sea covers all.

Opening in A minor, the song begins by creating a sonic image of the Deep Sea. As many before her had done, Beach associated the minor mode with sadness and saved its use as a home key for particular pieces. Similar to “April Dreams,” a descending bass line in A minor is present throughout the song, representing the depths of the Deep Sea. The syncopated block chords are reminiscent of the rocking waves of the ocean. When the pearl is introduced in the text, a C# is sustained in the left hand of the piano, suggesting that A Major may represent the pearl.

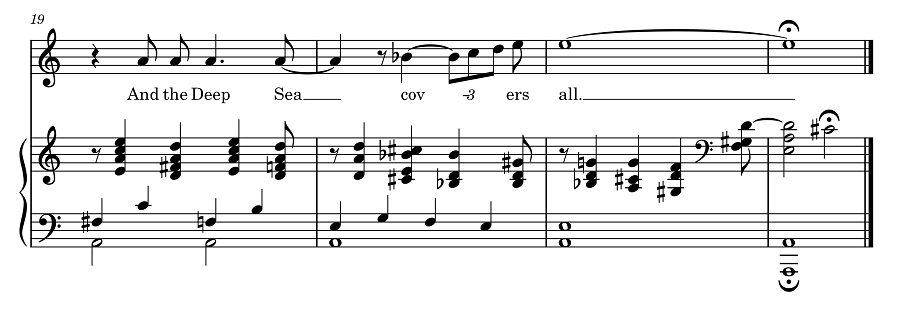

The musical setting of the second stanza sounds similar to that of the first stanza, with the descending bass line and syncopated block chords returning. However, the ending of the second stanza demonstrates the bittersweet theme of the poem perfectly. The pedal point of the tonic A is heard over and over again while the chromatic crunchy chords descend into the final harmonies. Unlike “April Dreams,” there is some sense of resolution in this song. A suspension over the pedal A resolves to a Picardy third. Our suspicions are confirmed that A major represents the pearl, hidden in the murky minor Deep Sea.

Returning to our original question about why Amy Beach elected not to publish these songs: though we will never know for certain, these songs were clearly personal for her, perhaps too personal. In a 1918 article titled “To the Girl Who Wants to Compose,” she reflected on a composer’s connection to their work. “It may be not only the creation of an art-form, but a veritable autobiography, whether conscious or unconscious.” Beach’s songs tell us more about her personal life than many of us initially realized. With over 120 songs composed, there is still much more to learn about Amy Beach and her songs, published and unpublished.

Notes

Mrs. H. H. A. Beach, “To the Girl Who Wants to Compose,” Etude 36/11 (November 1918): 695.

Adrienne Fried Block, Amy Beach: Passionate Victorian (NY: Oxford University Press, 1998).

Megan Lyons, “Unsung: A Corpus Study on the Art Songs of Amy Beach,” Ph.D. diss. (University of Connecticut, May 2022).

Great Performances, “The Lost Manuscripts of Composer Florence Price,” Season 49 (Episode 23).

Guest Blogger: Megan Lyons

Megan Lyons is currently an Assistant Professor of Music Theory at Furman University. Her research areas include music theory pedagogy, the songs of Amy Beach, and Joni Mitchell’s use of alternate guitar tunings. She has presented her research on Mitchell at national and international conferences, and currently serves as founder and co-chair of SMT-Pod, a venue that implements an Open Collaborative Peer Review Process to give authority to authors and maximize productive collaboration among peers.