Trauma marks the voice. Psychiatrist Erwin Randolph Parson talks about survivors’ trauma-voice in therapy, saying a voice “tells more about what really happened, and what has been broken and shattered inside than ordinary words ever can” (Parson 1999, 20). I ground my analyses of popular songs in this concept, showing how vocal timbre can powerfully convey symptoms of trauma in a way that lyrics alone just cannot. Sexual assault is unfortunately extremely common, especially in the music industry, and often leads to traumatic responses in the body. Katie Bain observes that, based on a 2021 survey by Midia and Tunecore, “nearly two-thirds of female music creators identified sexual harassment or objectification as a major issue.” Mark Savage agrees: “harassment [is] rife in the music industry because it present[s] a ‘very informal working environment, with late nights and alcohol consumption at gigs’ as well as ‘working one-on-one in a studio environment, and places with no windows’.”

Many women have written and performed songs about their experiences with sexual violence, and, I argue, they use vocal timbre to express the subsequent trauma that it causes. In this series, I describe three distinct ways that singers portray dissociation through their vocal timbre. First, in this post, I will show how consistent breathiness portrays derealization (or a disconnect from the world) in “Me and a Gun” by Tori Amos. In Part 2, I will examine how reverb portrays depersonalization (or a disconnect from the body), and how heavy vocal distortion portrays a dissociative disconnect from reality.

Dissociation, Depersonalization, and Derealization

In the most recent edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, or DSM-5, trauma is defined as “exposure to actual or threatened death, serious injury, or sexual violence” (2013, 271). Trauma rewires the brain and body, causing survivors to go into fight/flight/freeze mode on a regular basis, even when they are not actually in danger. When our bodies react in these ways, our brain cuts off functioning to the prefrontal cortex, where logical reasoning is processed, and reacts to seemingly mundane stimuli as if your life was in immense danger.

Dissociation, a consequence of the freeze trauma response, is “a defense mechanism in which conflicting impulses are kept apart or threatening ideas and feelings are separated from the rest of the psyche” (APA Dictionary). In other words, it’s when we separate from our body and reality in order to separate ourselves from the event (or something reminding us of the event). Everyone experiences moments in which their minds disconnect from what is going on around us. Think about spacing out during a boring lecture or daydreaming in the backseat of a long car ride. In these everyday situations, dissociation is natural, safe, and often pleasurable. In fact, people often seek out activities and creative outlets designed to elicit these mild dissociative experiences (trance music, meditation, e.g.). However, at more extreme levels, dissociation can be incredibly uncomfortable and, at times, even dangerous.

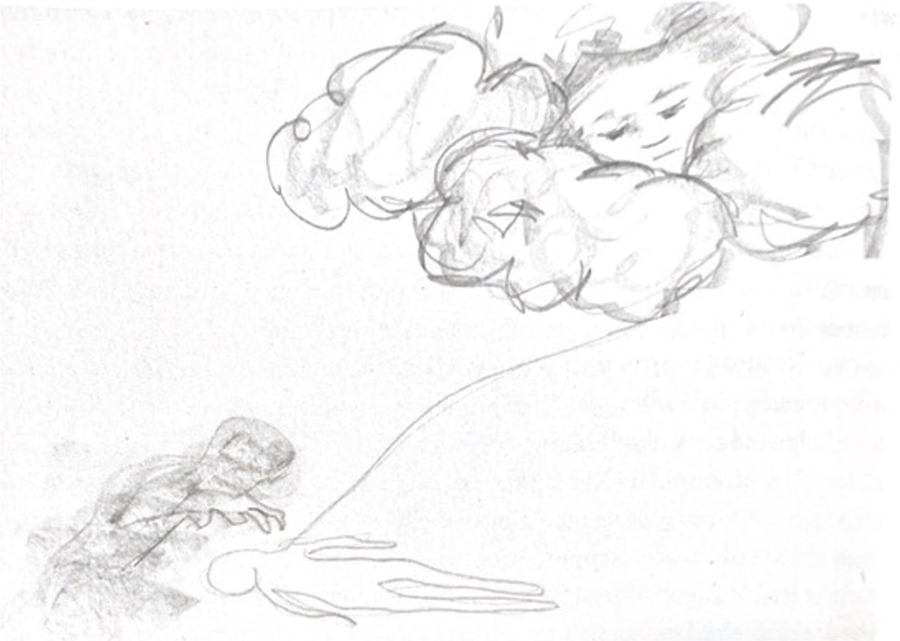

Many victims have explained how dissociation is more than just feeling numb, and results in feeling completely separated from one’s body, and/or from reality all together. For example, many survivors experience their assault, and sexual experiences after the assault, from a bird’s eye view. Marilyn, a patient of Bessel van der Kolk, provides the powerful drawing below of what she felt when her father was sexually assaulting her. Marilyn’s drawing not only provides a clear representation of how it feels to watch from a bird’s-eye view – with her face up in the corner watching down on the abuse – but also shows the disconnection from her own body and Self through the absence of clear features (such as a face, hair, hands, etc.) on the body at the bottom of the page. She draws herself as an abstract being, as if her body doesn’t belong to her; like it’s not real.

Her abuser is also shown as an abstract being, though his representation does, importantly, have a clearly drawn hand emerging from his darkness. This specific phenomenon, feeling literally detached from one’s body, is a specific type of dissociation called depersonalization, while a disconnection from your surroundings, including others, (or from your external reality) is called derealization. To put it simply, depersonalization is a disconnect from yourself, while derealization is a disconnect from the world around you, and they are both distinct forms of dissociation.

Though traumatic responses have been medicalized, and they do impede on survivors’ everyday lives, Sarah E. Wright (2020) maintains that trauma, unfortunately, is a normal occurrence and that our brains are merely doing what they can to keep us safe during and after a severely stressful event. My work draws upon this idea in order to emphasize the fact that these responses are common in people, generally, and especially within the music industry. Additionally, she emphasizes that “repeated storytelling promotes the activation of standard memory systems while the [traumatic] memory is told, encouraging it to be stored where other memories are stored and organizing it in its appropriate place in time” (192). Put simply, storytelling (like musicians do in their songs) can be extremely helpful in helping trauma survivors ease the intense emotions attached to their memories of the trauma, therefore helping the brain to categorize them in a way that helps the brain not to overreact to mundane stimuli.

“Me and a Gun” by Tori Amos (1992)

So how can we hear dissociation in the voice? What kinds of sounds come to mind to portray such immense numbness and separation from oneself? The song “Me and a Gun” by Tori Amos offers a moving example of breathiness and derealization. Amos released her album, Little Earthquakes, on January 6, 1992, after Anita Hill famously testified to Congress against her former supervisor, the now-Supreme-Court-Justice Clarence Thomas. Hill explained that he had sexually harassed her while they worked together for the Department of Education. The case sparked national controversy because sexual harassment and assault was brought into the public discourse against a national figure, and especially someone associated with the law.

Amos has discussed how this case inspired songs on Little Earthquakes, including “Me and a Gun.” In this song Amos records her thoughts during and after her experience of being raped at knifepoint [which she changes to a gun in the song]. She starts by discussing the period directly after the event, when she’s “still up and driving” at 5:00 a.m. because she “can’t go home, obviously.” As she sings about the actual assault, she starts to separate herself from the event, lyrically, as she dreams of seeing Barbados and Carolina, places that are literally far away.

About “Me and a Gun,” Amos wrote,

In ‘Me and a Gun,’ I’m the girl who’s raped. That is the ground that I covered. I did not cover the rapist’s point of view. (…) My having lived and survived this experience in real life wasn’t the only reason that I could write and perform from that perspective. I could do it because I could walk back into that violated space and sing it from that space without wavering. (Amos 2005, 10, my emphasis)

She explains that she can “walk back into that violated space,” describing that she is not only able to contemplate this experience and her feelings about it, but is able to embody her experience and “sing it from that space without wavering.”

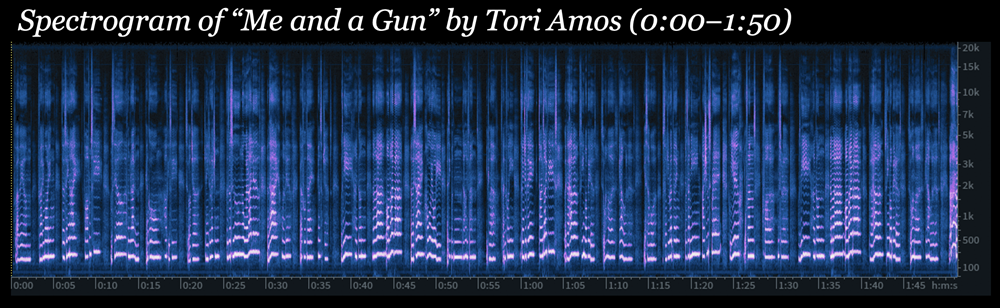

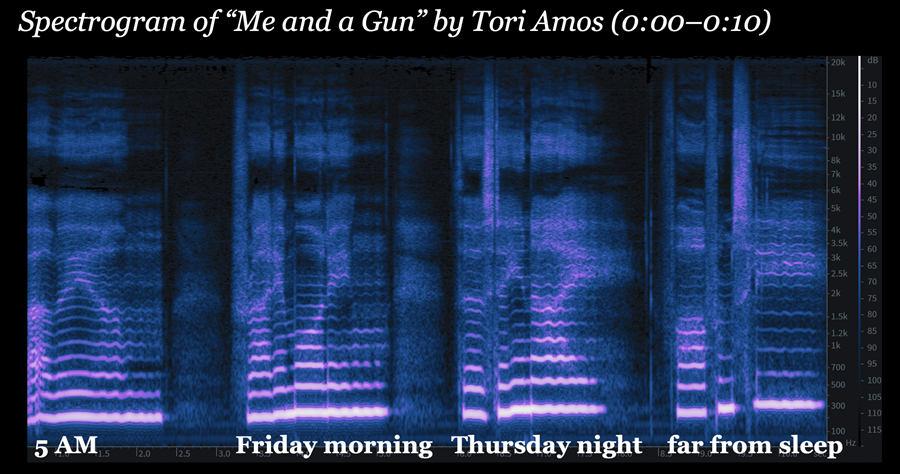

Vocally, Amos performs this song with eerie consistency in pitch, style, and volume, and without any accompaniment, which lets her voice alone truly carry her story. Here is a spectrogram of the first minute and fifty seconds of “Me and a Gun” to show, graphically, how consistent Amos keeps her breathy voice. Additionally, I include a zoomed-in spectrogram, which shows the fuzzy bands associated with a breathy sound.

Breathy tone is produced when the vocal muscle tone is very lax, as described by Victoria Malawey and Kate Heidemann, among others. Heleen Grooten (2023) notes that in states of low arousal “the [vocal] muscle tone is ‘hypotonic’ or slack; the voice becomes monotonous, flat, and often a little lower; speech is softer and slower.” (Grooten 2023, 36). Additionally, the vocal folds are literally more disconnected when producing breathy phonation. Because of the disconnection and low energy used to produce a breathy sound, and because these sounds are produced by people who are literally in low arousal states (such as dissociation), Tori Amos’s breathy consistency sonically portrays her intense numbness and disconnection from the world around her.

Amos decision to sing this song a cappella also adds to the eeriness of the song’s expression. It supports her portrayal of derealization, because there is literally nothing supporting her voice. She is disconnected from any other musical accompaniment, which conveys her disconnection from her surroundings. This is especially pertinent because Amos often accompanies herself on the keyboard, so she is separated even from her customary musical cloak. She sounds as if she’s in a tiny space all by herself, disconnected from anything else. As you listen, try to embody the sounds she creates with her voice.

In the second part of this post, I will consider how reverb affects meaning in “Dog Teeth” by Nicole Dollanganger and how heavy vocal distortion shapes the message of “Gatekeeper” by Jessie Reyez.

Notes

The banner photo is of Tori Amos by Adamantios. It was taken in 2007 before a concert in Berlin.

Amos, Tori and Ann Powers. 2005. Piece by Piece. Portland, OR: Broadway Books.

Bain, Katie. 2021. “Women Making Music Study: Sexual Harassment is ‘By Far The Most Widely Cited Problem.’” Billboard, March 25, 2021.

Cox, Arnie. 2017. Music & Embodied Cognition: Listening, Moving, Feeling, & Thinking. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders: DSM-5. 2013. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing.

Duguay, Michèle. 2022. “Analyzing Vocal Placement in Recorded Virtual Space.” Music Theory Online 28, no. 4 (December).

Harper, Faith G. 2017. Unf*ck Your Brain: Using Science to Get Over Anxiety, Depression, Anger, Freak-Outs, and Triggers. Portland, OR: Microcosm Publishing.

Heidemann, Kate. 2016. “A System for Describing Vocal Timbre.” Music Theory Online 22, no. 1 (March).

Koriath, Emily Jaworski, ed. 2023. Trauma and the Voice: A Guide for Singers, Teachers, and Other Practitioners. Washington D.C.: Rowman & Littlefield.

Kreiman, Jody and Diana Sidtis. 2011. Foundations of Voice Studies: An Interdisciplinary Approach to Voice Production and Perception. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell.

Malawey, Victoria. 2020. A Blaze of Light in Every Word: Analyzing the Popular Singing Voice. New York: Oxford University Press.

Mapes, Jillian. 2019. “The Chorus of #MeToo, and the Women Who Turned Trauma Into Songs.” Pitchfork, October 23, 2019.

Parson, Erwin Randolph. 1999. “The Voice in Dissociation: A Group Model for Helping Victims Integrate Trauma Representational Memory.” Journal of Contemporary Psychology 29, no. 1, 1999 (March): 19−38.

Porges, Stephen W. 2011. The Polyvagal Theory: Neurophysical Foundations of Emotions, Attachment, Communication, Self-Regulation. New York: W.W. Norton & Compan, Inc.

Savage, Mark. 2019. “Musicians ‘face high levels of sexual harassment.’” BBC, October 23, 2019.

van der Kolk, Bessel. 2014. The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma. New York: Penguin Books.

Wallmark, Zachary. 2022. Nothing but Noise: Timbre and Musical Meaning at the Edge. New York: Oxford University Press.

Wright, Sarah E. 2020. Redefining Trauma: Understanding and Coping with a Cortisoaked Brain. New York: Routledge.