In my previous post I discussed cover songs as a form of translation. Issues included whether a translation was free or literal, how meanings shifted with the gender of the singer, and the ability for translations to occur within a language in addition to between different languages. The examples all drew on young women covering Beatles’ songs. In this post I want to pursue the parallels between covering and translating to discuss a particular sub-category of covers; that is, covers that are original enough to generate their own covers, comparing them to the practice of translations of translations.

Rather than drawing again on Beatles songs, I turn instead to covers of Rolling Stones’ songs. This is the result of having received an unexpected and serendipitous response to my previous post from my brother-in-law, Edward Goetz, a life-long fan of The Rolling Stones. Answering my playlist with one of his own, he pulled together a remarkable set of covers by women of early Stones’ hits. In no ranked order, he countered my list with this eclectic set:

1. “Paint It Black” – Ciara (2015)

2. “You Got the Silver” – Susan Tedeschi (2005)

3. “Angie” – Tori Amos (1992)

4. “Tumblin’ Dice” – Linda Ronstadt (1977)

5. “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction” – P. J. Harvey and Björk (1994)

6. “No Expectations” – Della Mae (2015)

7. “Salt of the Earth” – Bettye Lavette (2010)

8. “Wild Horses” – Alicia Keys (2005)

9. “Play with Fire” – Ruth Copeland (1971)

Two preliminary points: Rolling Stones’ songs have not generated nearly as many covers as songs by The Beatles (something I documented six years ago); and many fewer women have covered them. According to the numbers now available on Secondhandsongs.com, the top two songs in terms of covers by men and women are “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction” (388, of which 39 are by women), and “Paint It Black” (305, with 28 by women). Because of lyrics that are sexist, racist, or otherwise problematic for women singers, few have tackled “Brown Sugar,” “Get Off of My Cloud,” “Lady Jane,” “Out of Time,” “Start Me Up,” and “Street Fighting Man.” Secondhandsongs currently lists no women who have recorded “Heart of Stone.” With lines like “There’s been so many girls that I’ve known / I’ve made so many cry, and still I wonder why,” this is not particularly surprising. Many of the women who have covered Stones’ songs have done so in the last twenty years. “Bitch” was first covered by a trio of women in 2011.

And yet, some women have successfully flipped the gender for one aggressively misogynistic song, “Under My Thumb,” as Tina Turner did. While Mick Jagger could boast that “the girl who once had me down” had straightened out now that he had her under his thumb, Turner reversed the direction of domination. Among other changes, she replaced “it’s a squirmin’ dog who’s just had her day,” singing instead about “the squirming worm who’s just had his day.” When she recorded this in 1975, she sang in the past tense about “the guy who once pushed me around,” but that was pure fantasy. She was still in the last throes of her abusive relationship with Ike Turner.

Covers of Covers

This cover of Turner’s raises directly the phenomenon of covers that refer more directly to an earlier cover than to the original recording. We’ll return to Turner’s recording. But first, to make clear my point, the classic example of a cover song that is so persuasive, so powerful that it eclipses the original is Aretha Franklin’s recording of Otis Redding’s song “Respect.” Most subsequent recordings of “Respect” are of Franklin’s cover rather than of Redding. She translated a song about domestic respect (the husband expects his wife to show him his “propers” in exchange for the money he brings home) into a feminist and racial anthem, a mid-1960s political cry for respect. In the nine months that Otis lived after Aretha put her stamp on his song, he embraced her changes, including her most memorable innovation, the spelling out of the central word, letter-by-letter: “r-e-s-p-e-c-t.” He died in a plane crash the day after this performance was filmed on 9 December 1967.

Redding figures prominently in another example. The ability of a cover song to reshape the live performances of the original performers – the performances of the original songwriters – shows up unequivocally in the Stones’ “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction.” As soon as it was issued on 6 June 1965, Redding seized on it, issuing his adaptation three months later on 15 September. Mick Jagger and Keith Richards had conceived of their song as a critique of modern consumer society. In verse one, they describe listening to ads on a car radio, getting “useless information / supposed to fire my imagination.” Verse two shifts to watching ads on television for laundry detergent and cigarettes. Only in verse three does sexual satisfaction arise, when “some girl” turns him down.

Otis Redding, instead, downplayed the aspects of consumerism, omitting the references to white shirts and cigarettes, saying only that the voice on the radio was trying to “mess up my imagination.” He omitted the second verse entirely, and instead emphasized the sexual connotation of “satisfaction.” Redding added verses at the end to plead his need for sexual satisfaction “earlier in the morning,” “later in the evening,” and “in the midnight hour.”

Guitarist Ronnie Woods eventually confessed that Redding’s cover shaped all of their subsequent live performances (McPherson). Indeed, Jagger took several elements: the “man on the radio” was not trying to “fire” his imagination, but to “mess” with it; gone is verse two; and near the end, he sings Otis’s lines about needing satisfaction “early in the morning,” and “early in the evening.” Here is a live performance from 1981 in Hampton.

Redding’s influence can also be heard in their 1969 performance in Madison Square Gardens, and still again in Glastonbury in 2013, when, after the lines about early morning and early evening, Jagger continued, ad-libbing “you got to do it like a Otis Redding.”

Taking a quite different approach to this song, the half-sung, half-spoken cover of “Satisfaction” by P. J. Harvey and Björk (1994) owes much to Devo’s automaton-like rendition (1978), recited as much as sung. Both omit a crucial element of the song, Keith Richards’ most distinctive guitar riff, substituting generic rhythmic guitar strumming. Harvey and Björk start slowly, softly, laconically, without melody, then gradually dial up the tempo, volume, and intensity, finishing where Devo starts.

This brings us back to Tina Turner’s recording of “Under My Thumb.” It can’t be compared to the influence of Franklin’s “Respect” or Redding’s “Satisfaction.” Veronica Falls (2011) and Courtney Love (2013) very much cover the Stones’ original, retaining the original words, and thus accept that they are women singing about subjugating another woman. And while Shemekia Copeland (2020) sings about a man under her thumb, she otherwise stays faithful to the Stones’ wording.

However, one woman clearly follows Turner’s lead. In 2015, Kim Carnes recorded a synth-pop version of the song, using Turner’s words, including the change of pronouns, the “squirming worm,” and the omission of the last verses. Much else is similar, including the tempo and the characteristic rasp of their voices. While Carnes had been performing “Under My Thumb” in this manner since the early 1980s, at the time she made this recording, remarkably, she was nearly 70 years old.

Translations of Translations

Covers of covers might be compared to paintings based on prints or photographs, or indeed, on other paintings (Picasso from Velazquez, Roy Lichtenstein from Picasso, numerous pop artists from Lichtenstein). They are interpretations of interpretations, translations of translations, which, indeed, are an age-old phenomenon. In 1695 Mark Micklethwait translated Olivaires of Castile, explaining on the title page that it was “Translated out of the Spanish into the Italian Tongue, by Francesco Portonari: And from the Italian made English.” But the Spanish publication was a translation from French, which was itself a translation from Latin. English was at least the fifth language in a chain of retellings (Orr, 146).

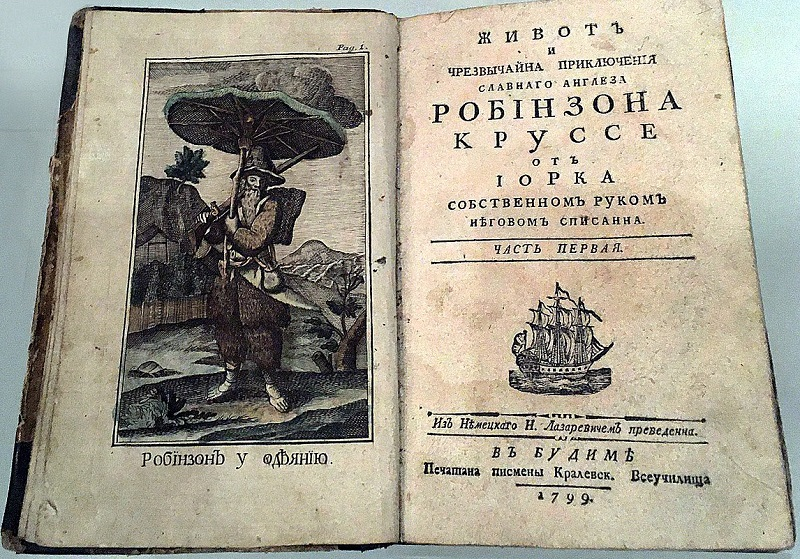

In the 18th and 19th centuries, Russian translations of English and Spanish novels were made not from English and Spanish, but from French. Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe, Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels, and Cervantes’ Don Quixote all followed this path. By the time Don Quixote was first translated directly from Spanish into Russian in 1838, there had been at least four versions derived from French (Watt, 224). Eventually Russian translations then became the sources of new versions of books in other Soviet languages. The Soviet Latvian translation of Robinson Crusoe from 1946 used as its source a Soviet Russian translation made in 1935, a version made in part to purge all of Defoe’s religious expressions (Tyulenev and Nuriev, 163).

Biblical translations from Hebrew and Aramaic into Greek, Greek into Latin, Latin into other languages, have frequently been translations of translations. Before Martin Luther published his German translation of the New Testament directly from the Greek in 1522, eighteen Bibles had been published in German starting in 1466, all of them translations from Latin (Bluhm, 111). Today there are numerous “modernizations” and “updates” to the language of the King James Version.

The vast majority of cover songs responds directly to the original song. Similarly, most books translated more than once are the immediate sources of all subsequent translations. Covers of covers, like translations of translations, are a sign that the original is in some way culturally significant, though in ways the first writer/composer never imagined. An artistic response capable of generating its own cover(s) changes the original in some significant way, creating a new message. Ultimately, the transformations of Franklin, Turner and others succeed as much for ideological reasons as musical.

Notes

Thanks for the prompt, Ed!

The practice I am discussing differs importantly from that known as “hijacking,” the practice in the 1950s of white musicians co-opting songs of Black musicians. See Michael Coyle, “Hijacked Hits and Antic Authenticity: Cover Songs, Race, and Postwar Marketing,” in Rock Over the Edge: Transformations in Popular Music Culture, ed. Roger Beebe, Denise Fulbrook, Ben Saunders (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2002), 133-58.

Heinz Bluhm, “‘Fyve Sundry Interpreters’: The Sources of the First Printed English Bible,” Huntington Library Quarterly 39/2 (1976): 107-116.

Ian McPherson, “Track Talk: Satisfaction” (2012).

Leah Orr, Novel Ventures: Fiction and Print Culture in England, 1690-1730 (Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Press, 2017).

Sergey Tyulenev and Vitaly Nuriev, “‘Sewing Up’ the Soviet-cultural System: Translation in the Multilingual USSR,” in Transnational Russian Studies, ed. Andy Byford (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2020): 155-68, 163

Ian Watt, Myths of Modern Individualism: Faust, Don Quixote, Don Juan, Robinson Crusoe (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996), 224.