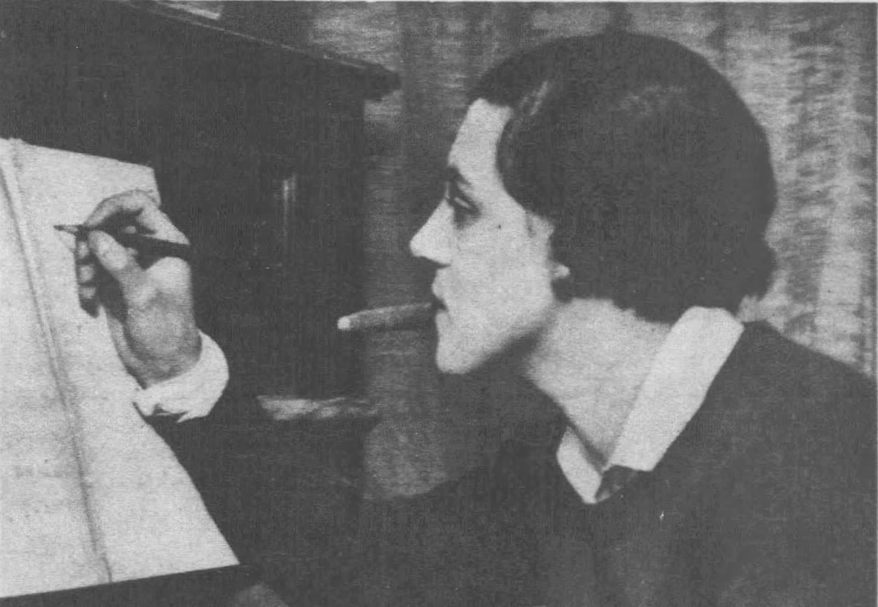

Although the theatrical weekly Variety didn’t print this remarkable photo, the editors found it newsworthy enough to describe it to their American readers in a short notice about “England’s youngest woman composer,” Vivien Lambelet. In their words, “she is wearing trousers on her crossed legs, a man’s shirt, collar and tie under a man’s pullover – and between her lips is a full-sized newly lit cigar!” (1 Dec. 1931).

For the possible stories it contains, this photograph is worth at least 1000 words. There is more than one way to read this striking image of a cigar-smoking female composer: is she mimicking a male composer she admires? Is she possibly emulating Ethel Smyth to make a political statement, or a statement about her sexuality? In other words, were her motivations personal, or professional? One reading doesn’t exclude another.

The Professional

Vivienne Ada Maurice Lambelet (1903–63) had a musical career that moved between two worlds, popular and classical. To navigate these different worlds, she identified herself variously as Vivienne and, for her publications, as Vivien, but she also employed the pseudonyms Eileen Hillyer and Raife Growenor.

She was the daughter of a British mother, Katie Buckton, and a Greek father, Napoleon Lambelet, a successful composer of songs and popular operettas in London. His father had been an eminent pianist and his father’s father a composer, making Vivien Lambelet at least a fourth-generation professional musician. Newspaper accounts identified her variously as a soprano, a mezzo-soprano, a pianist, a playwright, and an actress on stage and in films. She also composed and published at least 28 songs and some works for piano, as well as at least a few orchestral works.

Presumably, Lambelet began her music studies with her father, but her first acknowledged lessons were in Brussels, some years after the First World War (she was 15 when it ended), with the Belgian composers Arthur De Greef and Joseph Jongen. By fall of 1925 Lambelet had begun to record as a singer, popular songs like “When You and I Were Seventeen,” and “It’s a Man, Every Time, It’s a Man.” She also recorded under the name Eileen Hillyer. A recording Lambelet made in 1928 with Jack Padbury and his Cosmo Club Six – one of six she made with them – captures her light clear voice.

But Lambelet wasn’t just pursuing a career in popular music. Her early recordings coincided with a recital she gave at Wigmore Hall in 1925, as both a singer and composer. Among her own works was Les Quatre Saisons, for a reciter and small orchestra. The critic – with an acerbity that British critics had long cultivated – commented only, “Her ‘Seasons’ were remarkable for nothing, save that they came and went.” But he elaborated, wanting to point out her primary shortcoming: her Four Seasons “was all too obviously influenced by two other women composers, very successful ballad-writers in their time [possibly Liza Lehmann and Amy Woodforde-Finden]. No woman who wishes to compose should submit to feminine influence in her work.”

Within a year Lambelet began to publish her own songs, including a domestic set of Six Nursery Rhymes, but also an ambitious piece for piano on an exceedingly masculine topic, her “Spanish Intermezzo: To the Memory of a Toreador.” The music publishers Augener & Co. respected this work sufficiently to issue it also in an arrangement for orchestra, piano and harmonium. In 1926 she gave a second recital in Wigmore, singing in five languages, including modern Greek. According to a more generous reviewer, her voice “had no grandeur or ecstasy, but so neat and sensible a performance possessed real artistic merit.” Plus, he noted, she had a cold. Another reviewer detailed some of her repertoire: Respighi, five French songs, a set of Irish songs by Herbert Hughes. We can glean others from the details of her many radio shows (“wireless programmes”) from the preceding months: a mix of classical and light classical (Mendelssohn, Kreisler) and folk, African-American spirituals in arrangements by William Arms Fisher (“Deep River,” and “Every Time I Feel the Spirit”).

While she sang with dance bands and orchestras, she also was the top voice of a female vocal duo in 1926; two years later she had her own group, the “Vivienne Lambelet Trio.” Later in 1928 and into the next year, this group evidently added accompaniment and became known as the Baraldi Trio, with Ernest Baraldi on piano and a violinist or two as needed. She was usually identified as one of the two sopranos, but occasionally the listing specified that she was the middle voice (soprano II) of the three women. Among their recordings is this lovely one of Edward Elgar’s beautiful part song, “The Snow,” op. 26 no. 1. A score is available, which is helpful for picking out the middle voice.

Her Baraldi commitments ended when she returned to school. Lambelet won a scholarship for excellence in composition at Trinity College of Music, London, in fall 1930. Perhaps the music she wrote for the play, “A Wisp of Lace” (1930), factored into this decision. (In a 1936 revival she took this play on tour with several eminent actors and musicians, including Raymond Newell, Webster Booth, Gustave Ferrari, and conductor Albert Coates.) At Trinity she composed a short tone-poem, A Summer Afternoon (1931), which impressed her teachers for its “orchestral qualities.”

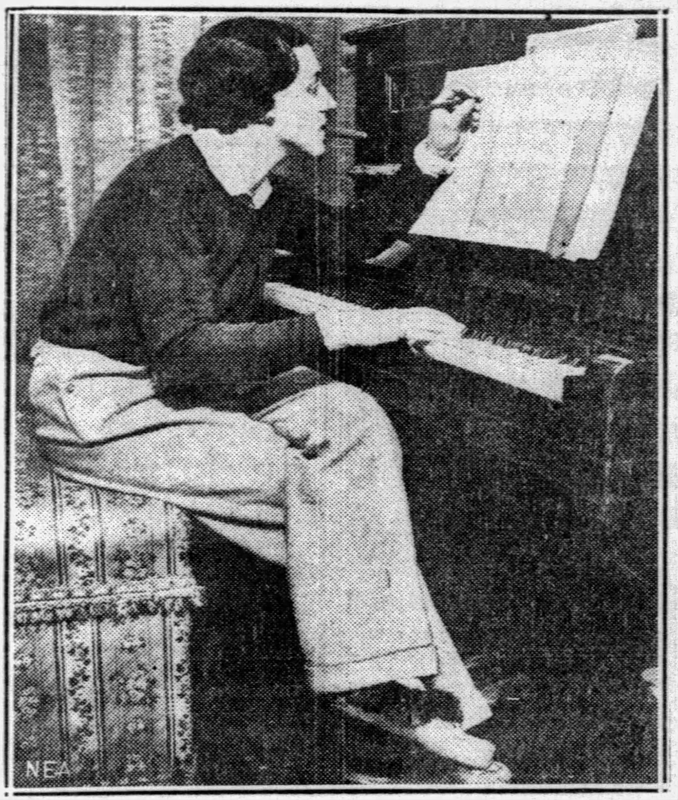

It was while finishing this composition, and also one called Phantasmagoria, that she had the provocative photo taken of her at the keyboard, smoking a cigar, wearing trousers and a pullover. According to the New York Daily News, John Barbirolli conducted the London Symphony Orchestra in a performance of A Summer Afternoon and Phantasmagoria: Symphony in A Flat, but the review in a local London newspaper mentioned only the first of these and identified the ensemble not as the LSO but as a Trinity College student orchestra in a concert on 5 Dec. 1931.

Despite Lambelet being completely unknown to North American audiences, newspapers printed this photo from coast to coast, usually with some version of this caption: “Puff, puff, puff – and another bar is completed! … That’s the way Vivien Lambelet, youngest London composer, finds she works best – with a black cigar between her teeth. Note the gray flannel trousers and the mannish jersey sweater, too.”

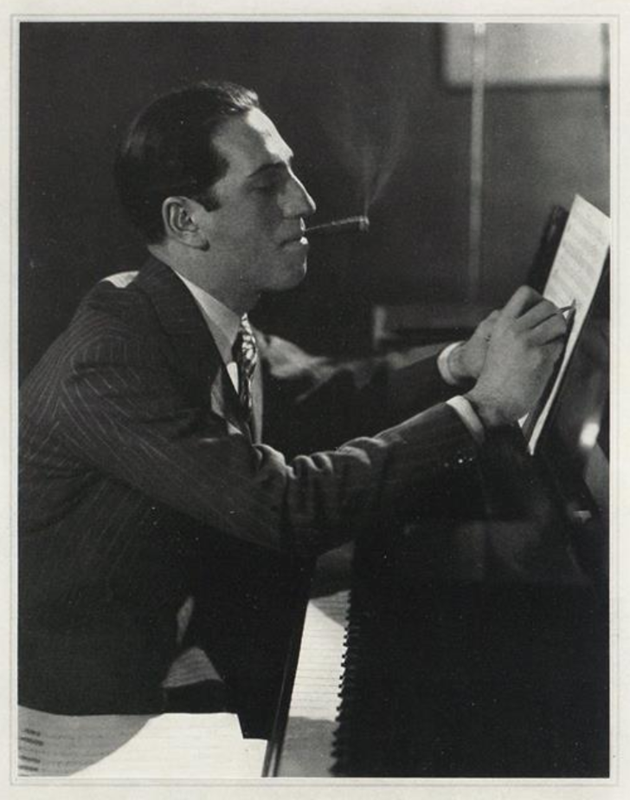

This photograph of Lambelet suggests a particular male influence. It bears a distinct resemblance to Edward Steichen’s photo of Gershwin for the January 1929 issue of Vanity Fair. The original had the perspective flipped, but perhaps under the influence of Steichen’s image, American newspapers often reversed it. Whether or not a critic recognized the nod to Gershwin, the “mannish” clothing and her masculine pose spoke for themselves, as did her two unfeminine acts – smoking and composing. Whatever the musical style of Phantasmagoria – the score seems not to have survived – the influence of Gershwin’s music in her song “Straws in My Hair” (Ricordi, 1934) is unmistakable (as it is in “Searching the World for Love”).

The Personal

By the 1920s in London, female cross-dressing did not necessarily indicate that a woman dressed as a man was a lesbian. Yet the details of Lambelet’s life in her last decades suggest that her masculine pose had personal as well as musical meaning. After two attempts at marriage – one actually took place – Lambelet settled down with a woman who was also an artistic collaborator.

Marriage attempt #1: Lambelet first agreed to marry Morgan Davies (1906-71), a Welsh singer who would soon become principal baritone at Covent Garden. They announced their engagement on 3 Sept. 1936. In late July they had sung together in a comic opera program on BBC Radio, and, just three days later, he proposed. Those impetuous plans fizzled soon after they were announced.

Marriage attempt #2: six months later, on 17 March 1937, she married Jay Johnston (1898-1967). An American from St. Louis, he had been an actor in Broadway musicals in the 1920s. He was 39 and she 33, neither previously married. According to a press release, “Miss Vivien Lambelet, the composer and singer … was married yesterday at Marylebone Register Office to Mr. Wensley Walter Johnston (known as J. Johnston), a United States author.” Together, they collaborated on a BBC radio play called “The Silent Melody” (1938); she, the author, hid behind the nom-de-plume, Raife Growenor. Credit for the radio version is given to Giorgio R. Foa and Wensley Johnston. The review in the Sunday Mercury (12 June 1938) notes that “as a singer of negro songs [Lambelet] has broadcast regularly since the beginning of broadcasting.”

The union didn’t last more than a year, if that. No census or civil register ever records them living together. By the beginning of the war he had returned to Missouri. There is no indication they divorced; he never remarried.

By the end of her first year of marriage, Lambelet had begun a close friendship with Barbara Rubien (born Courlander), a writer and pianist. Together they sailed to New York on 11 March 1938 on the ocean liner Manhattan, Lambelet travelling as Mrs. Vivien Wensley Johnston. They then lived together until about 1951, first in London (1939) but through the war and after in a large 17th-century house named Faggs Barn. Located in Steyning near the southern coast of West Sussex, it still stands.

During these years they occasionally performed as a piano duo, and they wrote and published four songs together. They also copyrighted several co-written songs in 1938 in New York, but evidently never published them. Among their joint efforts was “Wayfarer’s Song,” the theme song of the award-winning British film noire The Glass Mountain (1949), for which Nino Rota composed the score. For this song, Rubien used the pseudonym Elizabeth Anthony, a name she also favored as a writer of murder mysteries.

While living with Rubien, Lambelet composed “Ah, Do Not Be So Sweet” (1946), to a poem by Mary Webb that is poignant for the insecurity of the love it depicts. She urges her lover to be less sweet, less kind, less dear, because this will help her endure their separations. In the third and final verse, their love is portrayed as one better hidden from the “heavy-handed world,” a world better kept apart:

Ah, do not be so dear!

The heavy-handed world, if it should hear

And watch us jealously,

Would steal upon our love’s secure retreat

And rob our treasury.

Let us be wise, then; do not be too sweet,

Too dear, too kind to me!

The full text of Mary Webb’s poem is available. Gershwin-like passages emerge only now and then in Lambelet’s affecting setting. This is her voice.

In the early 1950s, Lambelet and Rubien moved six miles west to Sullington, living for several years several miles apart. After she and Rubien went their separate ways, Lambelet evidently composed no more. When she died, she left her assets, valued at 5287 pounds to a neighbor in Sullington, Katherine Harrild, a married woman living alone.

Ephemeral Fame

This is not a post I have had on my list of WSF essays that I hope one day to write. But the instant I saw Lambelet’s cigar-smoking photo, I read it as an allusion to Steichen’s photo. And so, I wondered: who is this woman I know nothing about? And what, if any, was her connection to Gershwin? Moreover, as I grapple with the most-successful-and-mostly-forgotten woman singer-songwriter of the 20th century, Carrie Jacobs-Bond, the question of forgotten celebrity is very much on my mind.

For someone who published as many songs as Lambelet did, who also wrote scripts and music for radio plays, and who was a radio celebrity, it has been unexpectedly challenging to piece together her career. Among the few songs that have been recorded since she died, there is “Faint Heart” (one of her first songs), “Ribbons,” and “Memory” (one of her last). Many thanks to Myrsini Margariti, soprano, and Effie Agrafioti, piano, and to Danae Eleni for their efforts to revive these undeservedly overlooked songs.

Notes

A complete list of her published songs is available in my Database of Women Song Composers, 1890 to 1930.

The photo of Vivien Lambelet, dated 14 Nov. 1931, first appeared in the London Sunday Express, 15 Nov. 1931. It was then described in Variety 104/12 (1 Dec. 1931): 49. American and Canadian newspapers quickly ran the photo. It is now included in the Popperfoto collection administered by Getty Images. The banner photo for this post is cropped from the New York Daily News (6 Dec. 1931). The date of Barbirolli’s performance of Lambelet’s orchestral work is recorded in the London Daily Telegraph (7 Dec. 1931).

On Lambelet’s early studies with Arthur De Greef: London Daily Mirror (29 June 1934). On her 1925 and 1926 recitals see Daily Telegraph (10 July 1925); Musical Times 67/1006 (1 Dec. 1926), 1125; and The Era (27 Oct. 1926). On her scholarship at Trinity College and her orchestral compositions: Musical Times 71/1051 (1 Sept. 1930), 843; and Musical Times 73/1067 (1 Jan. 1932), 66. The press release announcing her engagement to Morgan Davies appeared first in the Nottingham Journal (3 Sept. 1936); her wedding to Jay Johnston appeared in the Lancashire Evening Post and other papers on 18 March 1937.

Lambelet and Rubien are identified as a two-piano act in the Sheerness Guardian and East Kent Advertiser (6 May 1939). Information about the Atlantic crossing of Lambelet and Rubien in 1938 is from the National Archives; Kew, Surrey, England; BT27 Board of Trade: Commercial and Statistical Department and Successors: Outwards Passenger Lists; Reference Number: Series BT27-231779; accessed on Ancestry.com. They returned together on the Aquitania on 5 July 1938: The National Archives in Washington, DC; London, England, UK; Board of Trade: Commercial and Statistical Department and Successors: Inwards Passenger Lists; Class: Bt26; Piece: 1163; Item: 21

For the purposes of the annual electoral registers, Lambelet always identified herself as Vivien Johnston. Information about where she and Rubien lived is in the National Archives; Kew, London, England; 1939 Register; Reference: Rg 101/253c; and in West Sussex Record Office; Chichester, West Sussex, England; West Sussex Electoral Registers; Reference: WDC/CL73/1/130. Regarding Lambelet’s last will and testament, there is the Principal Probate Registry, Calendar of the Grants of Probate and Letters of Administration made in the Probate Registries of the High Court of Justice in England. London, England © Crown copyright. All accessed on Ancestry.com.