Florence B. Price’s proclivity for incorporating her personal experiences into her music is amply documented. Sometimes it is manifest in compositions that reflect on Price’s perspectives on the African American condition – works such as “Songs to the Dark Virgin” and “Judgment Day,” the fantasies nègres, and the Third Symphony, which Price described in a letter as “a cross section of present-day Negro life and thought with its heritage of that which is past, paralleled or influenced by concepts of the present day” (22 Oct. 1940). We see it also in occasionally quirky compositions such as My Neighbor’s Radio and Mosquitos in Convention, and in others whose titles, music, and/or text solicit autobiographical interpretation (for example, “Bewilderment” and the Song of Hope).

And it is evident in more abstract works such as Clouds, whose stylistic eclecticism shows the African American woman delving freely into idioms that white musicians considered the prerogative of white folk, not Black, with a freedom that parallels the consummate freedom of clouds themselves – a freedom that belies the racism and sexism that Price faced every day of her life. These and numerous other works impart too much of Price’s music a quality that is more than personal – it is confessional.

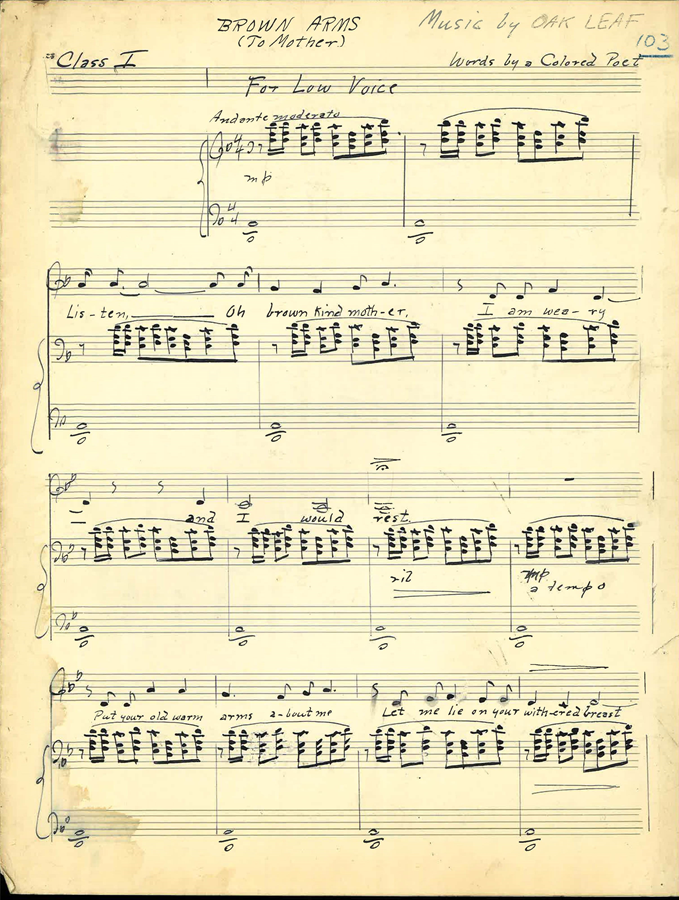

That confessional character is evident in the two songs that occasion this post. The earlier of these is “Brown Arms (To Mother)” (1931–32); the later, “To My Little Son” (ca. 1950). Because Price wrote only one securely dateable song before “Brown Arms (To Mother)” – “The Moon Bridge” (1930) – and only one securely dateable song after “To My Little Son” – the spiritual “Weary Traveler” (1951) – the two songs hold de facto inaugural and valedictory positions in her song oeuvre – positions that are profoundly poetic, as we shall see. Let’s examine these in reverse order.

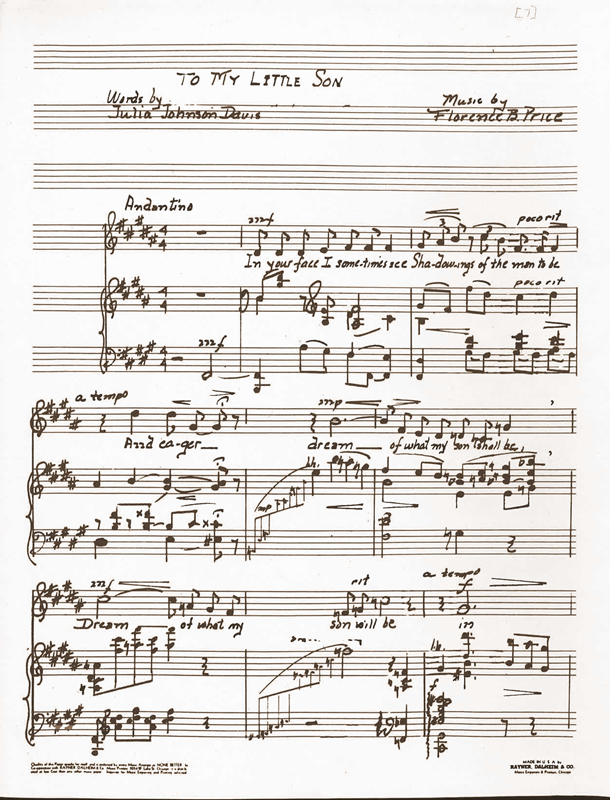

“To My Little Son”

“To My Little Son” has been a part of the musical world ever since it was first published in an edition by Rae Linda Brown in 2010, including regular performances as well as a wonderful WSF post by Stephen Rodgers. Rather than attempting to add to those interpretive insights, this post will offer a few supplemental and corrective facts and situate the song within the larger context of Price’s song output, with special reference to “Brown Arms (To Mother).”

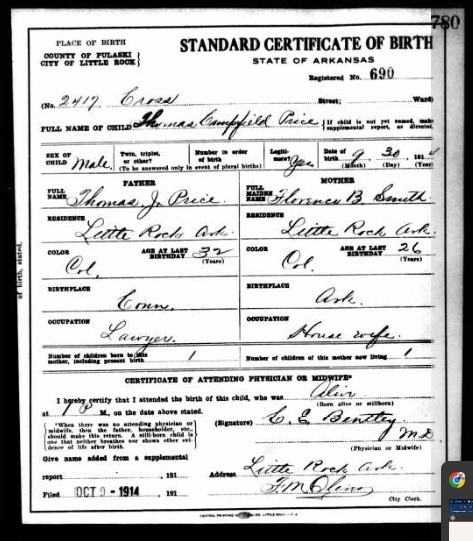

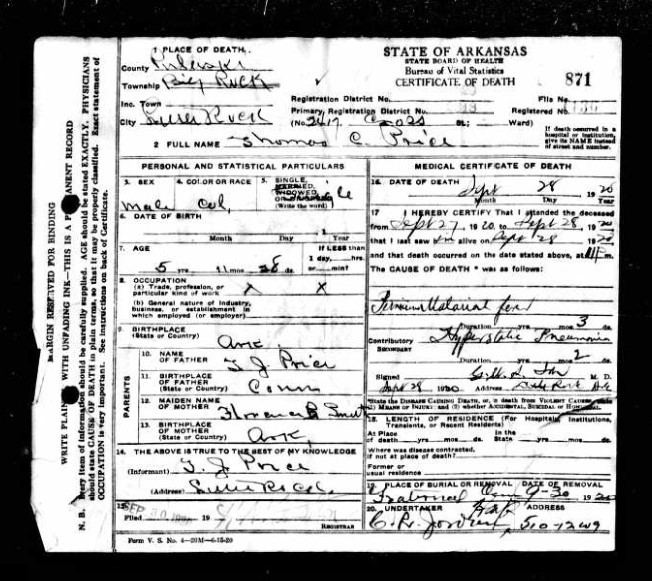

Crucial to understanding the relationship between these two songs is the chronological position of “To My Little Son” in Price’s oeuvre. Dr. Brown avers that the song was written “immediately” after the birth of the composer’s firstborn son, Tommy, whom she describes as having died “while an infant” (118). The child was born on 30 September 1914 and died in 1920, two days before his sixth birthday:

But “To My Little Son” was not written ca. 1920; in fact, all the evidence suggests that Price composed it ca. 1950 – i.e., near the end of her career, not at its beginning: first, the paper on which the autograph is written was printed by the Chicago firm of Rainer, Dalheim & Co. Price did not use this paper-type before the mid-1930s; second, the musical script in the autograph of “To My Little Son” is far removed from that of the surviving manuscripts of Price’s youth, but consistent with that of the late 1940s and early 50s; and third, the harmonic technique of “To My Little Son” is significantly more advanced than that of Price’s other surviving compositions before 1926 – and yet, these complexities notwithstanding, the song as a whole possesses a tone of indescribable tenderness perfectly in keeping with the simplicity of something a parent would sing to a young child.

There was at least one known performance of “To My Little Son” during Price’s lifetime, and this was likely part of a series of performances. The performers were African American contralto Carol Brice (1918–85) and her brother, Jonathan Brice (1911 or 1912–98). The known performance, part of the Brice siblings’ 1950–51 tour, was given on 2 November 1950 at Knoxville College (Tennessee), an historically Black Liberal Arts college. It was part of a series of performances they gave at other Black churches, colleges, and high schools.

But if “To My Little Son” can no longer be accepted as dating from around the birth of little Tommy Price, its revised dating only increases the song’s poetry – for the year of its probable composition, 1950, was the thirtieth anniversary of Tommy’s death. With this milestone in mind, it seems likely that Price, reflecting on the future manhood that neither she nor her son got to see, engaged as a composer in what Stephen Rodgers aptly termed the “time travel” of the poem itself, looking back over a distance of thirty years into a future that, as it turned out, never happened, and responding musically to its beauty:

To My Little Son (1924), by Julia Davis Johnson

In your face I sometimes see / Shadowings of the man to be, / And eager, dream of what my son / Will be in twenty years and one.

But when you are to manhood grown, / And all your manhood ways are known / Then shall I, wistful, try to trace The child you once were in your face?

“Brown Arms (To Mother)”

Florence Price lost her mother not to death, but to racism. If Florence Irene Smith, née Gulliver (1859–1948), ever had any doubts about the circumstances she would face in the Jim Crow South, they were dispelled by 1895, when she and Price’s father, Dr. James H. Smith, sued the White and Black River Valley Railway for discrimination, in the amount of $5,000 (slightly more than $184,000 today). But her resistance to the boundaries she faced as a Black woman came to a new head after the death of Dr. Smith in 1910. In March 1911, after settling her husband’s considerable debts (including a property dispute that eventually made its way to the Arkansas Supreme Court), the composer’s mother decided (in the words of Rae Linda Brown) that “she could take no more of being Negro, and worse, a southern Negro” (Brown, 317). She moved first back to her native Indiana and then to Pennsylvania, where she married a retired white florist in 1925 and spent the rest of her life passing as white, a decision that compelled her to destroy all evidence of her Black past and to sever all relations with her daughter.

We do not know for certain how Florence Price felt about her mother’s unimaginably painful decision, which occurred as she was concluding her career teaching at Atlanta University and looking forward to her marriage to Thomas Jewell Price (1881–1942). But we may imagine that the pain of that decision’s consequences had been greatly amplified by the early 1930s. By that time, the Price marriage had fallen apart (the divorce became final in January 1931), and the composer’s second marriage, to Pusey Dell Arnett, an insurance salesman thirteen years her senior, would soon enough end in separation. The composer was now in her early forties. In the throes of divorce, when many adult children can draw comfort from their parents, and the mother-daughter bond in particular often provides much-needed stability, Florence Price was a mother of two and herself effectively a motherless child.

Of these circumstances was born the song “Brown Arms (To Mother).” Price submitted it in Class I (“songs with words”) to either the 1931 or 1932 Rodman Wanamaker Contest in Musical Composition for Composers of the Negro Race. Although it neither won nor placed in the contest and remained generally unknown until January 2014, it stands as a bona fide masterpiece of song. Although its text was anonymized in accordance with the rules of the competition, it was written by John H. Owens of Flagstaff, Arizona, and published in several periodicals, among them the May, 1930 issue of The Crisis (information kindly provided by Douglas Shadle):

Listen, Oh brown kind mother, / I am weary, and I would rest. / Put your old warm arms about me, / Let me lie on your withered breast.

I am very sick of cities, / of faces cold and strange; / I long for your sun-washed spaces, / blue skies and wind-swept range.

I am sick of the huddled houses / And the selfish hearts of men. / Put your warm kind arms about me. / Let me lie on your heart again.

Those words are a confession of profound pain at maternal abandonment – but for Price, the poetry of song resided in the music as well as the words. And indeed, while the text of “Brown Arms (To Mother)” gives no more than a plea and the hope that a mother-daughter reunion will someday occur, Price’s wide-ranging music offers a glimpse of the feeling of that reunion itself. It begins with a direct entreaty to the lyric persona’s mother to hear the ensuing plea (this in a bleak D modal minor over a drone bass). But then it sets aside those “weary” tones as the lyric persona (Price), who had moved from Arkansas to the nation’s second largest city just a few years earlier, turns to a more chromatically complex section in lamenting that she is “very sick of cities” and longs for the “blue skies and wind-swept range” (an image graphically depicted in the piano part at 1’19” in the recording).

The opening drone, and the weariness it depicts, returns in m. 28 (1’42”), but Price – new to the crowded conditions of the urban north, and facing the disappointment and heartbreak of a failed marriage – confides that she is “sick of the huddled houses and the selfish hearts of men.” She longs for her mother’s embrace, to “lie on [her] heart again.” At this moment (2’10”), as the singer – the abandoned daughter – envisions the feeling of that maternal embrace, the music abandons the tone of isolation of the text; instead, it turns to something akin to joy as the work shifts to D major in the final section – suggesting the maternal embrace and a resolution of the gloom and abandonment with which the song began.

A Postlude

When Thomas Campfield Price was born in 1914, Florence Price in all likelihood could not share the news directly with Irene Gulliver Smith, for by that time the racism of their world had compelled her mother to leave her family and renounce her race. Neither could Price turn to her mother for support in time of grief when her little son died in 1920 – a vicious redoubling, surely, of the trauma and sorrows that an unaccepting white world had already placed before her. Her sole remaining source of support in time of sorrow was her husband, Thomas Jewell Price – but by 1931 that support, too, was gone from her.

Fortunately, by the 1930s Florence Price had discovered the joy and solace that musical composition had brought her – so she turned to song at the 20th anniversary of her mother’s departure, gifting the musical world with “Brown Arms (To Mother).” And by 1950, at the 30th anniversary of Tommy’s death, she knew that she had become a genuinely accomplished composer. She thus turned to song again at this occasion, pouring her complex emotions into “To My Little Son” and passing it to Carol and Jonathan Brice to share with the world of music lovers, many of whom had “little sons” of their own. After composing her beautiful and moving homage to her son, she returned to song one last time at age 62 to create a new, and biographically apt, setting of the ancestral spiritual “Weary Traveler.”

The point is clear enough: for Florence Price, confessional composer, the intimacy and expressive beauty of song offered a particularly effective outlet for exploring and coming to terms with loss. Although the white world around her persisted in the dehumanizing oppression that had led her mother to renounce both her race and her family, the Black community, represented here by Carol and Jonathan Brice and the audiences at the Black civic institutions where “To My Little Son” was performed, lifted up Florence Price as a composer. As that community listened to Price’s musical voice, collectively they became the “brown kind mother,” offering her the embrace of “warm kind arms” for which she had cried out nineteen years earlier.

Notes

Florence Price’s letter of 22 Oct. 1940 to Frederick Schwass was quoted in Rae Linda Brown, The Heart of a Woman: The Life and Music of Florence B. Price (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2020), 318.

“Brown Arms (To Mother)” is available in Florence B. Price, Seven Songs on Texts of African American Poets, ed. John Michael Cooper (Fayetteville, AR: ClarNan Editions, 2024). The autograph manuscript is in University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, Special Collections, shelfmark MC 988b Box 1C, folder 32.

“To My Little Son” was published in an edition by Rae Linda Brown in 2010 (Fayetteville, AR: Classical Vocal Reprints). The autograph manuscript is in University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, Special Collections, shelfmark MC 988a Box 13, folder 37.

The sources for the birth and death certificates for Thomas Price are Arkansas Department of Vital Records. Birth Certificates and Death Certificates, Little Rock, Arkansas.

WSF recently published a playlist of songs by Florence Price.

This post has been updated to correctly identify the poet of the poem “To Mother.”

Guest Blogger: John Michael Cooper

I am Professor of Music at Southwestern University in Georgetown, Texas, and the main contributing editor of Hildegard Publishing Company’s Margaret Bonds Signature Series, which is currently slated to include 34 more editions of previously unpublished music. I have also edited and published 60 previously unpublished works by Florence B. Price (G. Schirmer). My recent book Margaret Bonds: “The Montgomery Variations” and Du Bois “Credo” appeared with the New Cambridge Music Handbooks Series (2023), and Margaret Bonds. Composers across Cultures, is currently in press with Oxford University Press. You can learn more about me here.