This past month, the British ensemble Fieri Consort have released their album, The Excellence of Women: Casulana and Strozzi (Fieri Records, 2024), which supplements the premiere recording of Maddalena Casulana’s Primo libro de madrigali a cinque voci and a handful of her four-voice madrigals, with some select madrigals, duets, and solo song by Barbara Strozzi. The album’s programme extends a concert given by the group for International Women’s Day 2022, which was broadcast live by the BBC and relayed to the European Broadcasting Network.

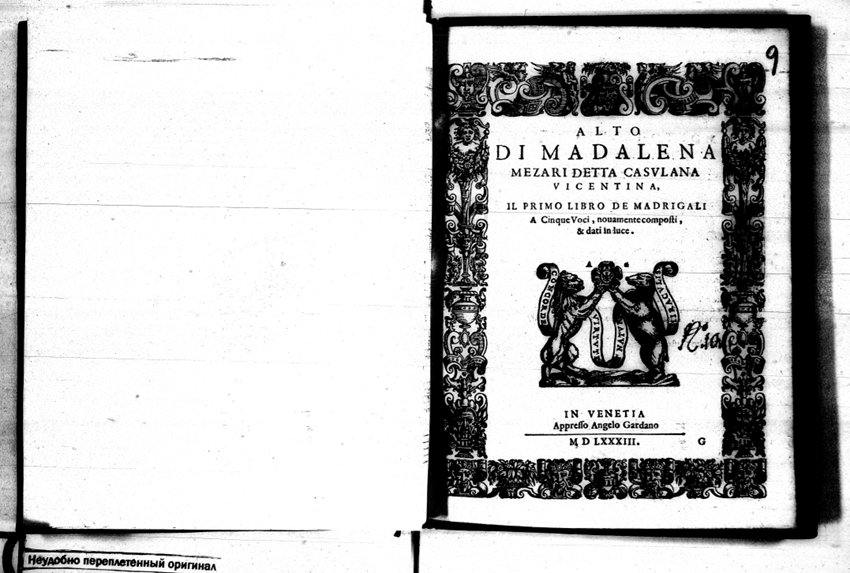

The months leading up to that broadcast, and this recording, were a whirlwind of discovery, plotting, secret negotiations, and finally the Big Reveal – when the UK’s Observer newspaper splashed the news on the front page: that I had located the lost Alto partbook of Casulana’s five-voice madrigals in the Russian State Library. The five partbooks of these madrigals had previously been held by the Gdańsk Library of the Polish Academy of Sciences, but the Canto and Alto partbooks went missing in the aftermath of looting during World War II. So for the first time in the modern era, we would be able to perform, hear, and study the music Casulana wrote in in the genre that was her own time’s standard of excellence.

Who was Maddalena Casulana?

The most widely known fact about Maddalena Casulana is that she was the first woman to publish an entire book of music under her own name. Her Primo libro de madrigali a quattro voci appeared in 1568 (only its Canto and Tenore partbooks survive). Its dedication to Princess Isabella de’ Medici Orsini is often quoted for its unabashed criticism of those who would detract from women’s musical skills:

“These first fruits of mine, flawed as they are … show the world (to the degree that is granted to me in this profession of music) the foolish error of men, who believe themselves the masters of high intellectual gifts, which – it seems to them – cannot be equally common among women.”

Casulana’s male peers (mostly) held her in very high regard, and she clearly moved in the most esteemed musical circles across Europe: there are traces of her in Florence, Milan, Venice, Paris, and Munich.

Yet, Casulana remains a mysterious figure, and the details of her life are scarce. Happily, Professor Catherine Deutsch of the Université de Lorraine is currently writing a monograph on Casulana (with Cambridge University Press). And she has begun to fill in some vital details. We know from the research Deutsch has presented at conferences that Casulana had at least two husbands, and two children; that she was a war refugee in the 1550s; and that she had to litigate her first husband’s family for her dowry after he left her destitute. Deutsch hopes in the fulness of time to be able to help answer the pressing question of how Casulana obtained her musical education – how, in fact, did she get to be such a skilful composer?

Why are Casulana’s five-voice madrigals so important?

Just on the merit of doubling the number of available pieces by a groundbreaking composer, the completion of Casulana’s First Book of Five-Voice Madrigals is hugely important to musicians and musicologists. But the discovery also allows us to understand Casulana much better as a composer. Until the Alto part of the five-voice madrigals was rediscovered, our assessment of her was based solely on her four-voice madrigals, of which one book, the Secondo libro de madrigali a quattro voci of 1570, is preserved complete.

Casulana’s four-voice madrigals are, in themselves, beautifully wrought. Many of them give the appearance of being solo song, composed out into four parts for the purpose of publication (virtually all music published in the 16th century was issued in partbook format, with the individual voice parts published in separate booklets). We know that Casulana was a lutenist and a singer, so we can safely assume that at least some of these works were for her own use as a performer.

However, by 1570, the four-voice madrigal was losing its cachet as a compositional genre: musicians who were eager to display their technical skill were turning to the five-voice madrigal as better evidence of their prowess. Following the lead of the mid-century maestro, Cipriano de Rore, the big beasts of the late 16th-century madrigal – Luzzasco Luzzaschi, Giaches De Wert, Marc’Antonio Ingegneri, Luca Marenzio, Carlo Gesualdo, Orlando di Lasso, Filippo de Monte – all published most in the five-voice format, again regardless of how the music was originally conceived in performance.

Having Casulana’s five-voice madrigals completed allows us to compare her style directly with that of these composers, much as her patrons and audiences, in the refined salons (or ridotti) of the north Italian academies would have done. And clearly Casulana was as skilled as any of her peers in harmonic and melodic invention, and in creating settings that honor the conceit and structure of her texts.

Casulana’s five-voice madrigals were published in 1583, but some of them may date as far back as the 1560s. The cycle “Aura, che mormorando al bosco intorno” has four sections, the third of which (in four voices only) first appears in her 1570 book. In this early work, we can hear that Casulana has already developed a mastery of scale and long-range harmonic structures. On the other hand, many of the five-voice works are miniatures lasting barely two minutes in performance, yet each finely crafted to match music to text.

Casulana was not afraid to place herself visibly in the highest ranks of compositional achievement. Her four-voice madrigal “O notte, o cielo, o mare ,o piaggie, o monti” quotes Cipriano de Rore’s famous “O sonno, o della queta umid’ombrosa” in its opening bars (compare Fieri’ Consort’s rendition by soprano and viol with Musica Secreta’s recording of De Rore’s madrigal with the same instrumentation).

Casulana’s five-voice “Come esser puote Amore,” uses Nicola Vicentino’s chromatic genus (banning melodic major thirds in any voice) after the first phrase to create a contrast that heightens the conflicted feelings of the poet. And her use of winding chromatic harmonies in “Dolce e vaghi augelletti” is never without a lightness of touch that prevents the music from moving forward (when we were recording this piece in October 2022, one of the singers said, “Oh, like Gesualdo … but better.”)

Casulana in performance

Fieri Consort is primarily a vocal ensemble, but the members have embraced fully the idea that the 16th-century madrigal is not defined solely by its publication format. They see the scores as templates for a much broader instrumental and vocal palette. For this recording they are joined by bass viol, harp, and lute, and the pieces may be performed with all five voices and all three instruments, with a solo voice and one instrument, as duets, or unaccompanied, creating a listening experience that better illustrates the wide range of options open to the 16th-century ridotto musicians. The instrumentalists have also recorded two works from Casulana’s First Book of Four-Voice madrigals, which I completed for them by providing new Alto and Basso parts.

Fieri Consort’s capacious approach also helps the listener make a stronger connection between Casulana’s works and those of Barbara Strozzi, even though there are nearly 80 years between the first publications of both composers. Strozzi’s first book contains five-voice madrigals as well as the solos and duets for which she is more famous: she, too, perhaps saw the value of demonstrating her compositional skill as a polyphonist to a doubting public.

*

I do not believe that either Maddalena Casulana or Barbara Strozzi wanted to be remembered as a “woman composer.” They both expressed a weariness with defending their right to practice their craft, let alone to have their compositions judged without reference to their sex. So, while we can acknowledge that musically creative women have experienced barriers for centuries, we can celebrate their achievements on their own merits.

The rediscovery of Casulana’s missing partbook has made this so much easier, and I am looking forward to hearing and reading much more about her in the near future.

Note

The news of Laurie Stras’s discovery of this missing partbook has been widely reported, including in The Guardian, Gramophone, BBC, and EBU.