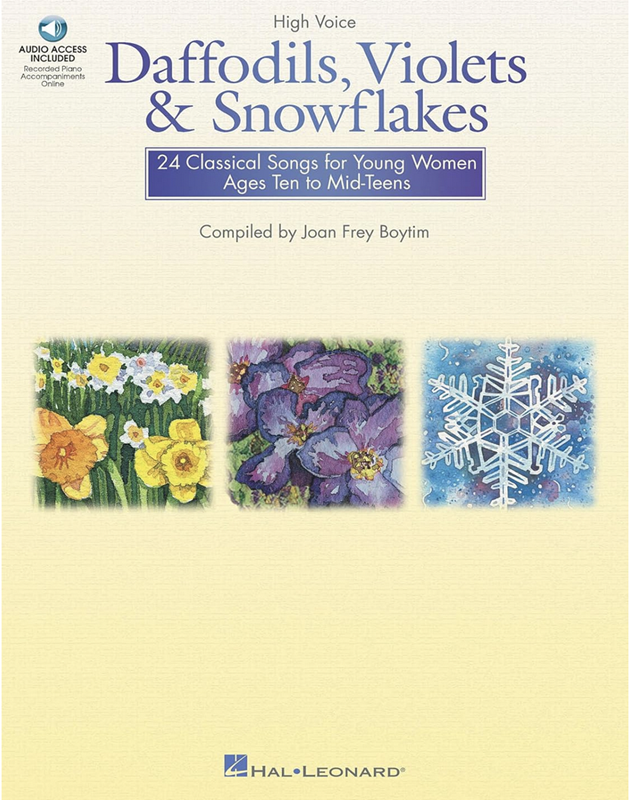

For over twenty years, the Hal Leonard company has sold an anthology entitled Daffodils, Violets & Snowflakes: 24 Classical Songs for Young Women, Ages Ten to Mid-Teens. Compiled by noted pedagogue Joan Frey Boytim (1933–2024), who through her career edited more than 60 vocal anthologies, the volume comes with online audio of piano accompaniments. Between 2011 and 2023, Hal Leonard sponsored an online vocal competition that encouraged voice teachers to assign Boytim’s choices to their female students. Approximately 150 YouTube videos feature well-dressed little girls performing songs from Daffodils, Violets & Snowflakes, and all but one of the winners of the “Ages 12 and under” category of the final competition sang selections from the volume.

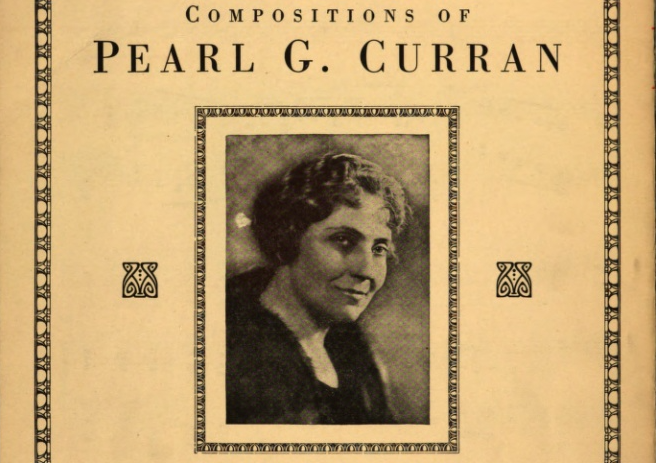

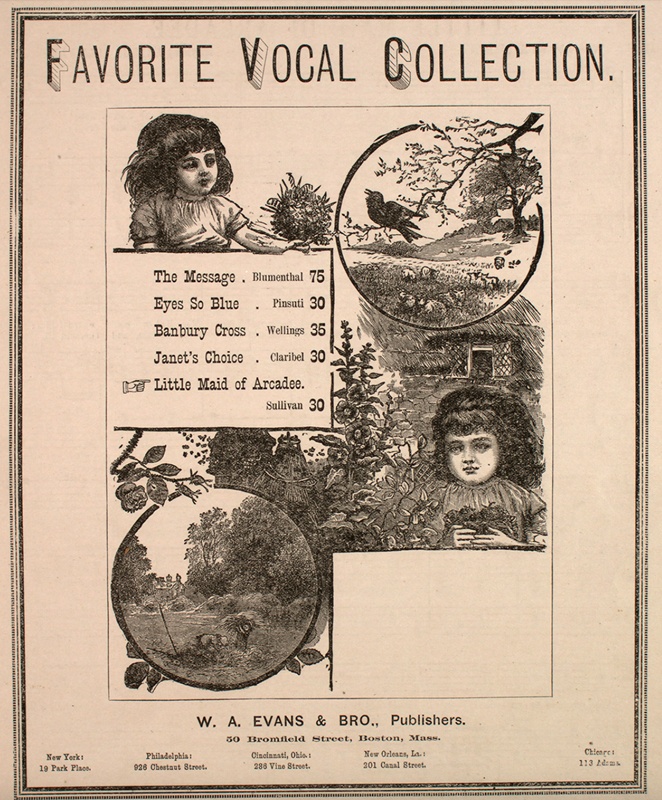

So where did the selections intended for young girls come from? The anthology’s contents are almost entirely by American and British composers, five of whom are women (Pearl Curran and Harriet Ware were subjects of previous WSF essays). Most of the songs first appeared between 1900 and 1922. Hal Leonard simply reprinted works no longer under copyright. Thus, today’s voice students can encounter composers more familiar to their great-great grandmothers, such as Charles Gilbert Spross, Liza Lehmann, or Oley Speaks. The anthology’s best-known figure is Arthur Sullivan, whose “Little Maid of Arcadee” was the single published number from Thespis, his unsuccessful initial collaboration with W. S. Gilbert in 1872.

Many of the volume’s songs were popular in their era and remained so during Boytim’s own childhood. Roughly a third of them can be heard on early sound recordings. British contralto Clara Butt sang Franco Leoni’s “The Leaves and the Wind” and Henry Brewster’s “The Fairy Pipers,” as did Sigrid Onegin. Metropolitan Opera soprano Anna Case recorded Anne Stratton Miller’s “Boats of Mine,” which was also published in an anthology of her repertoire in 1920. Hermann Löhr’s “You Better Ask Me,” was heard on record as late as 1950, sung as an operatic duet by Joan Sutherland and Edwin Liddle. Two of the oldest songs, “An April Girl” and “The Minuet,” appeared in an 1885 anthology of musical settings of poetry from the children’s magazine, St. Nicholas. The lyrics of the latter song were regularly featured in turn-of-the-century elocution books aimed at women and children.

Daffodils, Violets & Snowflakes mostly contains repertoire not originally intended for child singers. Nonetheless, Boytim’s notes suggest that the volume is appropriate for girls due to the level of technical demands and because of its themes, which include nature, love, flowers, birds, wind, and spring. Many of the songs on these topics remain appealing despite their age. The catchy tunes of Curran’s “Ho! Mr. Piper,” which depicts dancing fairies, long considered an appropriate subject for children, has led to frequent recordings by competition participants. Miller’s hazy and evocative “Boats of Mine” is one of the rare songs that specifically evokes childhood. Its rocking melody, suspended over static harmonies, increases in movement as the singer’s boat floats away to be recovered later by other children.

Unfortunately, most of what is intended to make the volume appropriate for girls relies on lingering female stereotypes. Surprisingly, girls themselves only appear in a few of these songs. The grown women depicted are typically the object of male desire and are often engaged in work: “Kitty of Coleraine” carries milk from the dairy and “Mollie Malone” sells cockles and mussels before her untimely death. Even without the physical presence of women, the songs’ imagery – fairies, flowers, and small animals – helps to associate the feminine with the diminutive. Multiple songs involving birds link the high sounds of girl’s voices to tiny twittering animals.

It’s not a stretch to imagine that spring, flowers, and love suggest the budding fertility of the teenage girls who might sing these songs. Stereotypes that link the feminine to nature instead of to civilization (cast as masculine), have long plagued women and the music by and for them. Composer Mary Carr Moore complained, “So long as a woman contents herself with writing graceful little songs about springtime and the birdies, no one resents it or thinks her presumptuous.” (Smith and Richardson, 173) Similarly, when little girls sing cute songs about flowers and blowing breezes, there is no indication that they will grow up to achieve anything that requires them to assert agency.

Daffodils, Violets & Snowflakes suggests no future for young girls other than romance. “Why Don’t You Ask Me,” in which a woman suggests that her male suitor propose to her instead of seeking permission from her parents, seems particularly archaic in the twenty-first century. And in an age in which we are far more aware of the sexual exploitation of children, Lehmann’s “Daddy’s Sweetheart,” about a little girl who wants to marry her father is, well, sort of creepy, especially for Boytim’s intended audience, which includes junior high students.

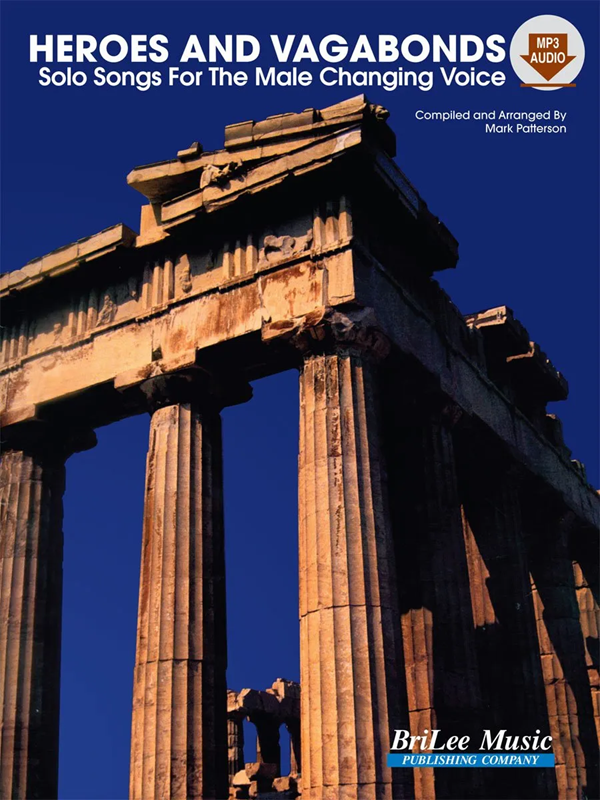

Several music educators have pointed me to Heroes and Vagabonds: Solo Songs for the Male Changing Voice, the anthology that they consider to be the masculine counterpart to Daffodils, Violets & Snowflakes. Published the same year, the arrangements of folk songs by Mark Patterson for young men demonstrate notable differences in their gender expectations, casting the girls’ songs into even clearer relief. Patterson’s selections feature only a few overtly male stereotypes, such as in “The British Grenadiers,” which hails military heroes, or “The Skye Boat Song,” about the vessel carrying “the boy who’s born to be king.”

The overall theme of the volume is travel – boys, it seems, are free to move through the world. Girls’ boats leave them behind, but boys can sail off to sea or take flight, even if metaphorically. When Patterson’s selections mention romantic love, it usually involves leaving a woman, such as in the sea chantey, “I’m Bound Away.” Somewhat troubling is that the boy’s lyrics often imply more introspection and emotional depth than anything in the girls’. Boys can request that someone express “thoughts of the soul” before parting or call for the “swift wings” needed to achieve their dreams. Amidst the tales of flowers and fairies, the girls’ songs rarely provide the sense that their singers have thoughts, feelings, or ambitions.

As charming as the songs of Daffodils, Violets & Snowflakes might be, young people growing up today deserve better than music that reinforces antiquated stereotypes. Perhaps, instead of simply reprinting repertoire composed before American women had achieved the right to vote, publishers should provide anthologies with more diverse offerings. Today’s girls encounter women as athletes, astronauts, and presidential candidates. Where are the songs about girls building, traveling, and achieving—dreaming of their futures? Music publishers would do well provide girls with repertoire that recognizes their potential and reflects their worlds.

Notes

Boytim, Joan Frey, ed. Daffodils, Violets & Snowflakes: 24 Classical Songs for Young Women, Ages Ten to Mid-Teens (Milwaukee, WI: Hal Leonard, 2003).

Patterson, Mark, ed. Heroes and Vagabonds: Solo Songs for the Male Changing Voice (Nashville, TN: BriLee Music Publishing, 2003).

Pratt, Waldo Selden, ed. St. Nicholas Songs: With Illustrations (New York: The Century Co., 1885).

Smith, Catherine Parsons, and Richardson, Cynthia S., Mary Carr Moore, American Composer (Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 1987).