How can we use cycles to raise the visibility of women composers? And what is a song-cycle, anyway? Many years ago, I had a revelation when I realised that the ‘cyclical’ works many of us know and love, such as Johannes Brahms’s Die schöne Magelone, op. 33, or Schubert’s Die schöne Müllerin, were almost never performed as complete, uninterrupted sequences in the 19th century. Brahms even explicitly stated that he thought it inadvisable to programme more than a few of his songs consecutively (Loges, “Pushing”). Schubert left no documented opinion on the matter, but hearing more than a few of his songs performed consecutively would have been unthinkable to him, simply because no one did it. Even Robert Schumann, who thought very deeply about cycles, could not expect nose-to-tail performances of his collections. His wife Clara Schumann programmed his Dichterliebe in two blocks, divided by solo piano repertoire (Loges, “From Miscellanies”). Cycles could be published as collections, but these did not map directly onto performance.

The Paradox of Song Cycles

This is all straightforward history gleaned from primary sources, but it seems to make little difference to our ongoing fascination with thinking of cyclical works as inviolable wholes. And after all, cycles are not only a useful organisational framework for listeners (both scholarly and amateur), but also an effective business strategy for performers and promoters. The most fascinating example is surely Schwanengesang, a group of songs collated after Schubert’s death by his astute publisher Tobias Haslinger in 1829. For many, it remains the third ‘great cycle’ – despite being no such thing.

But if the power of cycles bypasses history and logic, then women surely need more cycles! We see how a cycle is boosting the popularity of Lili Boulanger; her Clairières dans le ciel crops up ever more frequently on concert programmes and in scholarship, and is even being shortened to ‘Clairières’ in conversation – a sure sign of canonisation, just as we might talk about Müllerin. A more subtle example is the Femmes de Legende. These piano pieces were not conceived as a cycle by the French composer Mel Bonis (1858–1937), but emerged over many years. They were collected, strategically titled and then published as a set in 2003. Since then, they have been performed as a 24-minute cycle of seven pieces by various pianists, including Elisabeth Pion and Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau’s granddaughter Elena.

Viardot’s Mörike ‘Cycle’: Practice Research as Historic Recovery

If making a cycle effectively platformed a thoughtful collection of some of Bonis’s wonderful piano repertoire, might the same strategy also work for her earlier older contemporary, Pauline Viardot (1821–1910)? With this question in mind, I want to see if I can co-harness history and theory to re-imagine a song cycle by Viardot. This brilliant and storied musician should need no promoting, but in truth, few of my colleagues know her music, thanks to the usual hindrances surrounding women (the lack of a complete edition or recording, coupled with her absence as a composer from general musical histories).

Unlike Bonis’s Femmes de Legende, Viardot did actually write a cycle on the poems of Eduard Mörike during the 1860s, when she lived in Baden-Baden in southwest Germany. As Christin Heitmann has shown, on 11 March 1865, Viardot’s Russian friend and companion Ivan Turgenev wrote to the writer and illustrator Ludwig Pietsch, about a ‘whole cycle’ of recently-composed Mörike songs by Viardot (Turgenev-Urban, Letter 20). In a letter dated 14 April 1865, Pauline Viardot offered the Leipzig publisher Barthold Senff ten songs on Mörike for publication as a collection. No reply from Senff has been found, and no cycle was published, but this is unsurprising; in the conservative 1860s, a German publisher would not have accepted a German song-cycle by a Frenchwoman of Spanish origin, moreover a singer.

Remarkably, Viardot composed this cycle at a time when the Swabian priest-poet Eduard Mörike was relatively unknown. None of her contemporaries or predecessors had explored Mörike’s poems on this scale. Hugo Wolf’s settings appeared over twenty years later, so Viardot should really be credited for ‘discovering’ Mörike as a song poet. We don’t know exactly how Viardot’s contemporaries understood the word ‘cycle’ – but even if she meant a collection from which musicians could make selections, I have argued above that this interpretation would not be effective for listeners today.

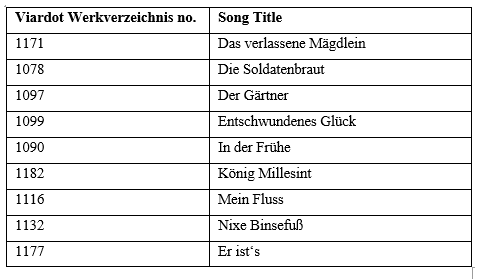

However, Heitmann’s archival work shows that only ten out of twelve songs can be located (see the table above). “La Nuit” appeared in French as late as 1895 and is a special case, discussed below. Six of these were published from the late 1860s onwards, in individual editions or mixed collections. Four remained unpublished during Viardot’s lifetime. To date, there is no information about the order in which they were conceived, written down, or performed.

The surviving material is just around 28 minutes – a perfect recital second half, just like Dichterliebe, a little longer than Schumann’s Frauenliebe und -leben. The question is: how might we perform these songs as a cycle? My answer draws on a conception of practice research which is not only experimental, but also committed to real-life contexts, i.e., what works on the stage rather than the page. Such research frequently also has an activist purpose, used to foreground the voices of women and minoritised people for whom archival material can be scarce.

A number of modern editions have appeared, but a major obstacle in realising the Viardot-Mörike cycle is the co-existence of different sequences. All are labours of love and scholarly expertise, but they do not convey the same coherent message that Haslinger so skilfully conveyed about Schwanengesang – a message that was reinforced by popular editions like Peters and countless recordings. One attempt at a sequence is proposed by Miriam Alexandra Wigbers, who published the songs in her edition of Selected Songs, Volume 2 (German songs):

Treating the Viardot-Mörike songs as an experiment in cyclic construction raises many questions; most importantly, what principles should determine the order of the songs? Some options are: to follow the sequence in the Breitkopf-Wigbers (or another) edition; to construct an alternative order based on key (or other purely music-theoretical) relationships; or to devise a sequence based on dramaturgy, character and narrative. The first option, as exemplified by the Breitkopf-Wigbers sequence, does not present an effective musical close. Turning to option 2: theorists (and many pianists) adore tonal connections, but does anyone really hear them outside the artificial world in which we can listen ‘from above’? Indeed, current research suggests that only a quarter of non-expert listeners can hear if you play a melody in one key and the accompaniment in another! (Kopiez-Platz). So, purely music-theoretical harmonic principles should not drive decision-making. A more fruitful approach may be gleaned from dramaturgical programming strategies of the nineteenth century – option 3. Open-ended starter songs, with motoric energy, work well (as in Müllerin and Winterreise); here, Viardot’s “Der Gärtner” is an excellent equivalent.

And how to finish? If we recall the enormous success of Robert Schumann’s “Frühlingsnacht”, which closes his Eichendorff-Liederkreis, we can argue that an upbeat ending with some ‘big’ singing is effective, no matter how gloomy or introspective the preceding songs were. Indeed, “Frühlingsnacht” was the crowd-pleaser extraordinaire, used to close countless small sets of songs throughout the century. With this logic, I would end with Viardot’s shimmering, optimistic “Er ist’s” (rather than the fascinating but lengthy “Mein Fluss”, as in the Breitkopf edition). Within these two bookends, I could construct a loose narrative from infatuation to triumph.

Such ideas recall the strategies musicologists have used to affirm (or, rather, construct) the cyclic nature of Dichterliebe, Die schöne Müllerin and Winterreise, none of which actually have clear narratives. In the case of the Viardot-Mörike songs, we can use the narrative songs as scaffolds, while the lyric songs can be inserted as expressive digressions. When this is tested in practice, other aspects of a performance-driven dramaturgy emerge, such as the value of periodically showcasing the singer’s range and colours, or the pianist’s virtuosity and lyricism.

There are other possibilities which I won’t discuss here, such as working with the sequence in the 1838 edition of Mörike’s poems, or including ‘La Nuit’ in translation and piano arrangement, or declaiming a selection of unset poems (the latter would only really work in a German-speaking context, or in a fine translation). But ultimately, only a consistent practice will allow the songs to be regarded as a cycle. Speaking from experience, I find that a sense of coherence also inevitably emerges from the repetitions which rehearsal affords. And my perception of this emergent coherence will, in turn, inform the confidence and conviction underpinning both the performance, as well as the story I weave around this wonderful music. As there will be a complete performance in Marbach in July 2026, decisions will have to be made, and I will publish an update afterwards which draws on insights from the musicians and the audience.

Why is all this necessary?

There are, arguably, many other women and marginalised figures who would benefit from such treatments. After all, Pauline Viardot is far more famous than many other women musicians, even though her lack of a famous husband or brother, coupled with her controversial lifestyle, excludes her from the category of ‘approved’ women like Clara Schumann or Fanny Mendelssohn. Her contemporaries, male and female, admired her compositions almost without reservation, yet her songs remain strangely invisible. On one hand, a world-famous singer like Cecilia Bartoli has shown interest since the 1990s; see this lovely recording of the song “Haï luli”.

On the other hand, even as new complete Schubert, Schumann, Wolf and Brahms song recordings continue to emerge, there is no complete edition, recording or performance guide to Viardot’s songs. And above all, there is no model for programming such a scattered, messy musical legacy – a problem I am working on. So, interventions are needed, as for the sublime “La Nuit”:

To exclude this outstanding song from the cycle feels downright wrong, but including it is equally tricky because it is stylistically distant from the rest of the set, and it is in French translation! The first step is arranging it for just piano and voice, removing the obligato violin and cello which make it expensive to program (my thanks to Maurice Florin, Hochschule für Musik Freiburg, for undertaking this task). The second step is tackling the issue of language – restoring the original German. This is a longer discussion with wider implications for Viardot’s multilingual song oeuvre. Her cosmopolitanism (she worked in six languages) is at once impressive and intimidating, and translation strategies – again, commonplace in her century – are needed.

When an oeuvre consists of numerous small items, as is the case for many women, I argue that grouping in cycles are essential to rediscovery. And ‘rediscovery’ involves making decisions about curation, as Haslinger understood two hundred years ago. What begins as one person’s decision may become culturally valid with time. Such projects have limitations, of course; in order for the Viardot-Mörike cycle to take root, it needs to attract stakeholders across the cultural spectrum, across scholarship into pedagogy and practice.

The most compelling argument for Viardot as a composer is simply this: her exquisite musical intelligence and her ability to bring poems to life through song – as all her contemporaries repeatedly acknowledged. If anyone wants to try out the cycle as we will perform it, do get in touch.

Notes

The first version of this post was given at the conference “her*hits: Liedkomponistinnen. Gesucht, gehört, gefeiert,” hosted by the Forschungszentrum Musik and Gender, Hochschule für Musik, Theater und Medien Hannover (June 2025). An extended essay will appear in the fall.

Viardot’s letter of 14 April 1865 is cited in https://www.pauline-viardot.de/9Werk.php?werk=246 accessed 26 December 2025. Christin Heitman, “Pauline Viardot. Systematisch-bibliographisches Werkverzeichnis (VWV),” since 2012.

Bibliography

Alexandra, Miriam and Eric Schneider – Deutsche Lieder (Oehms Classics, OC1878)

Borchard, Beatrix. Pauline Viardot-Garcia: Fülle des Lebens (Cologne: Böhlau, 2016).

Daverio, John. “The Song Cycle: Journeys Through a Romantic Landscape,” in German Lieder in the Nineteenth Century, ed. R. Hallmark (New York, Routledge, 2010).

Ferris, David. Schumann’s Eichendorff Liederkreis and the Genre of the Romantic Cycle (Oxford: Oxford UP, 2000).

Heitmann, Christin. “Pauline Viardot. Systematisch-bibliographisches Werkverzeichnis (VWV).” Since 2012.

Kopiez, Reinhard and Friedrich Platz. “The Role of Listening Expertise, Attention, and Musical Style in the Perception of Clash of Keys,” Music Perception 26 (2009): 321–34.

Loges, Natasha. “Detours on a Winter’s Journey: Schubert’s Winterreise in Nineteenth-Century Concerts,” Journal of the American Musicological Society 74 (2021): 1–42.

______. “From Miscellanies to Musical Works: Julius Stockhausen, Clara Schumann and Dichterliebe,” in German Song Onstage: Lieder Performance in the Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries, ed. N. Loges and Laura Tunbridge (Bloomington: Indiana UP, 2020) 70-86.

———. “Julius Stockhausen’s Early Performances of Franz Schubert’s Die Schöne Müllerin,” 19th-Century Music 41/3 (2018): 206–24.

———. “Pushing the Limits of the Lied: Brahms’s Op. 33 Romanzen,” in Brahms in the Home and the Concert Hall: Between Private and Public Performance, ed. Katy Hamilton and N. Loges, (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2014), 300-23.

Perrey, Beate Julia. Schumann’s Dichterliebe and Early Romantic Poets: Fragmentation of Desire (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2022).

Turgenev, Ivan Sergeevič, and Peter Urban. Werther Herr! Turgenevs Deutscher Briefwechsel (Berlin: Friedenauer Presse, 2005).

Van Rij, Inge. Brahms’s Song Collections (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2010).