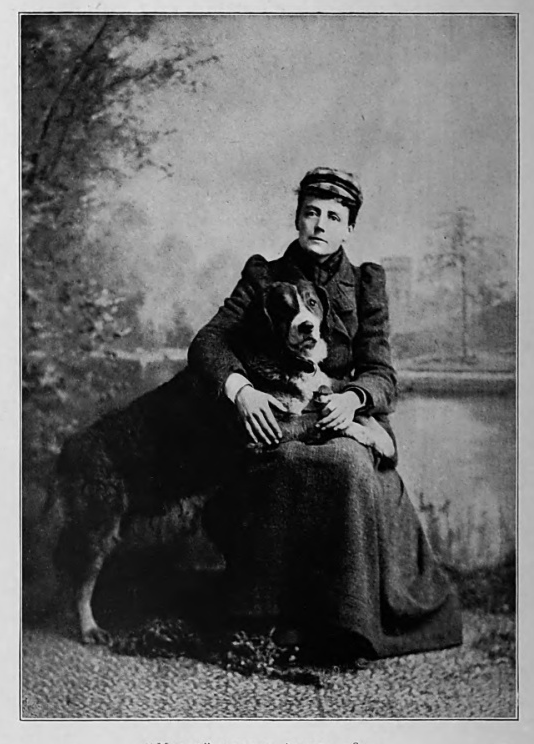

Dame Ethel Smyth (1858–1944) was a hugely significant figure in British history. She received her damehood for musical composition, reflecting her composition of several operas, diverse chamber music, and – perhaps her best-known contribution – the song “March of the Women,” beloved by other militant suffragettes.

Her personal and political life, which included relationships with Emmeline Pankhurst and collaborator Henry B. Brewster, has made her an important figure in LGBTQ+ history. Leaving home to receive a musical education in Leipzig led to performances across Europe. Smyth advocated what she called “mixed bathing in the sea of music,” wanting orchestras, choirs, conductors and concert organisers to afford sufficient creative opportunities to both sexes, something that she argued that she had lacked on regular occasions simply by being a woman.

The Importance of Manuscripts

As a music historian, I’ve always been interested in manuscript sources and their survival. The value of original sources is not only a question of their heritage, but also of the chance to glimpse a composer’s creative process, whether towards a final version or as a window on the regular revisions through which pieces were adapted to new circumstances or ideas. There is something about making a personal connection with musicians of the past that makes working with original sources about more than just the nuts and bolts of which notes were written down when.

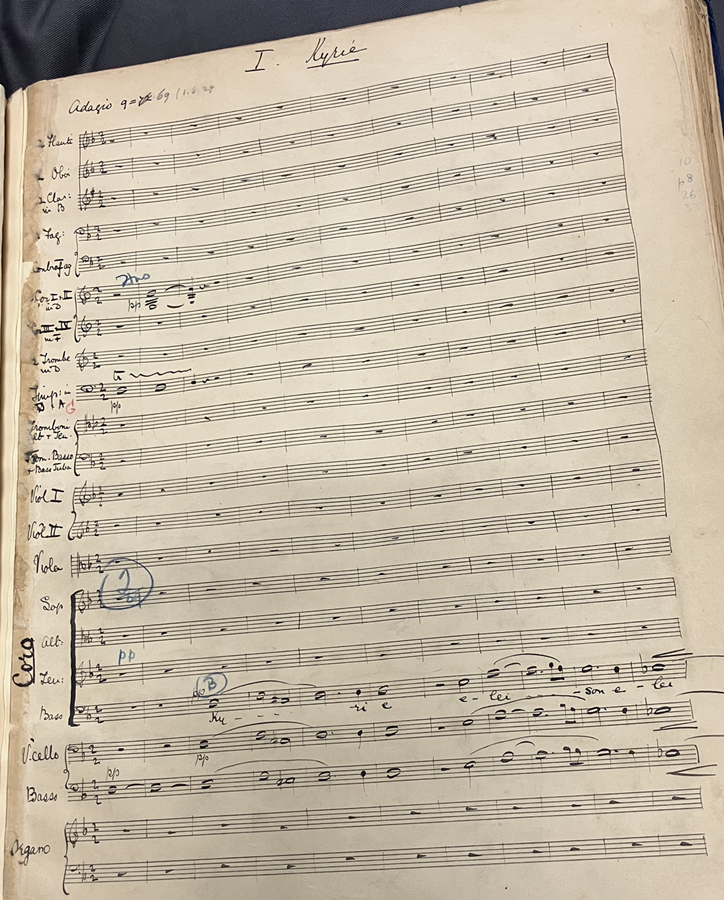

Manuscripts sources for Ethel Smyth exist in several locations, with most in London (the British Library, the Royal Academy of Music, and the Royal College of Music) and in Durham. In February, just two months ago, I saw an entry in the University of Liverpool Special Collections and Archives catalogue that listed the “Full score in the autograph of the composer” for the Mass in D amongst the holdings. What I knew from the published list of Smyth sources compiled by Jory Bennett in 1987 and from dissertations completed in the 1990s by Robert Marion Daniel and Linda J. Farquharson, as well as other studies, was that the original manuscript was at that point considered “lost.”

Because she was a voracious writer of letters and postcards, today many archives in England and across Europe also hold copies of Smyth’s correspondence, which can shed light on her musical career and her experience as a woman composer in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The Composition of Mass in D

Smyth’s Mass in D was one of her major works, composed in 1891 in her early thirties and first performed in 1893 at the Royal Albert Hall. In order to secure that performance, conducted by Joseph Barnby, Smyth needed Novello to print enough vocal scores for the choir, and had assistance in copying out parts from George Henschel, an acclaimed conductor who was also a close friend of Johannes Brahms. This was no small undertaking: the Mass lasts about an hour, with parts required for soloists, orchestra and organ.

After the premiere the Mass went without a significant public performance until 1924. Smyth reflected on the process towards the work’s revival in concert and in publication, for which she had searched her house, finding first only “a couple of limp and dusty piano scores,” but then, “after agitated further searchings, the full score turned up in my loft,” where it had been “appreciated by the mice.”

Having found her own original manuscript, presumably the one from the 1893 premier (though this is a matter for further research), Smyth worked with Sir Adrian Boult to mount the Mass in Birmingham, where Boult had recently been appointed to conduct the City of Birmingham Orchestra. This performance, and one in London a few weeks later, were reviewed far more positively than the one in 1893, perhaps as a result of changes in social attitude rather than any radical revisions of the piece.

Decades of Neglect

There are many reasons why Smyth’s Mass was neglected between 1893 and 1924. Sydney Grew, writing for the Musical Times in 1924, felt that the piece had been overlooked largely for “economic” reasons. “The 1890s,” wrote Grew, “was a busy period,” with new works by Parry, Stanford and others entering the repertoire, “asserting themselves to the disadvantage of their slightly elder relatives.” Grew admired Smyth’s writing, including its harmony and counterpoint, praising the Mass as the product of a “well-trained and natural musical mind.”

Smyth was rather less forgiving, blaming not a crowded market but one in which women were not welcome. A 1927 letter discussing the reception of the Mass and its revival by Boult, now held with the Liverpool manuscript, claims: “That I am a woman, is the main bar. If that Mass had been written by Parry or Stanford!!! … well! There it is!”

The musical style is bold, with an energetic approach to text and expression. Of the Gloria, which Smyth requested is placed at the end of the Mass rather than in its customary position after the Kyrie, Grew remarked: “The choral opening of the Gloria is so strong rhythmically that the blow it strikes on our imaginations ought to vibrate all through the performance.”

In a sense, the original manuscript was never really lost, only out of sight and mind. When Smyth thought it lost in the early 1920s, it had simply been hiding in the attic where she’d left it. Smyth’s donation of the full score to Boult was part of her effort to secure the legacy of the Mass in later life. As she wrote in the score itself:

To Adrian Boult, who, after it had lain for 31 years in the grave, splendidly brought this Mass to life again – the original score is offered by his old friend, Ethel Smyth (March 1938).

Rediscovery

Smyth’s act of bequest, and Boult’s later donation of the manuscript to the University of Liverpool, ensured the manuscript’s expert conservation, but also resulted in a lack of awareness among musicologists as to its whereabouts. One has to search the library catalogue to find reference to it, and Liverpool seems an unusual place to look, unless one also knows of Boult’s role in the Mass’s revival and of his own gifts to the library. Thankfully, the archivists at Liverpool had collectively pulled out a range of entries regarding music sources in their holdings that might be of interest to researchers in our department – the wording of the catalogue, identifying the composer, the piece, and the fact that this was a full autograph score, was a clear and accurate description of the nature of the manuscript itself, waiting for the eyes of an informed researcher to identify its central role in the performance history of Smyth’s music.

The serendipity of my career move to work at the University of Liverpool, my research interests in manuscript sources and transmission, the cataloguer’s knowledge, and my university education at Huddersfield and York in the history of women composers – all of these contributed to me recognizing the potential significance of the catalogue entry made by the Special Collections and Archives team.

Seeing the original manuscript on 4 March gave me shivers down my spine. I spent the next few days consulting Smyth specialists Leah Broad, Amy Zigler and Hannah Millington in order to be assured that the manuscript was not already well-known. The timing of International Women’s Day on 8 March added fire to our bellies to announce and celebrate the find online. No doubt there will be more work to do, individually, collectively, and by researchers across the world, to understand the full significance of the new source. Next fall the manuscript will be displayed to the public as part of the Lightbulb Moments Exhibition at the Victoria Gallery & Museum, University of Liverpool (September 2025).

It is equally thrilling to me to announce that University of Liverpool Special Collections and Archives have just made the digitized copy of the full manuscript available to everyone.

What Next?

As a document reflecting both the original concept of the Mass and its performance history, there can be no better primary source. Of particular interest for the future are the ways in which this manuscript, whose core copying seems to belong to the original conception of the work, reflects the many ways in which it was used by the composer, copyists, and conductors (including Smyth herself) in the years between 1890 and 1938. Most pages include some form of revision, clarification, correction or annotation in a range of coloured inks and pencils; there are pastedowns in many places, covering the previous text with a revised one or blanking it out completely.

Marginal notes reflect the standard markings that the choir would need to place in their printed copies for an orderly performance: “SIT” appears for periods of respite for the hard-working choir, and one warning to tenors and basses of their fast-approaching entry read simply, “Look out men!” A century later, this admonition could also be read as a statement to Parry, Stanford, and her other male colleagues that Smyth intended to venture onto musical turf they considered their own.

Notes

The manuscript of Smyth’s Mass in D is in University of Liverpool Special Collections and Archives, LUL MS 68.

Robert Marion Daniel, Ethel Smyth’s Mass in D: A Performance Study Guide (Ph.D. diss., The University of North Carolina at Greensboro, 1994).

Linda J. Farquharson, Dame Ethel Smyth: Mass in D (Ph.D. diss., University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 1996).

Sydney Grew, “Ethel Smyth’s Mass in D,” The Musical Times 65/972 (1 Feb. 1924): 140-41.

Ethel Smyth and Ronald Crichton, The Memoirs of Ethel Smyth Abridged and Introduced by Ronald Crichton; with a List of Works by Jory Bennett (London: Viking, 1987).

Guest Blogger: Lisa Colton

Professor Lisa Colton is Head of Department and Chair in Musicology at the University of Liverpool. Her research interests are especially focused on music in medieval England and France and on women’s musical lives. Her books include Angel song: Music in Medieval English History, Music and Liturgy in Medieval Britain and Ireland (with Ann Buckley), and Female-Voice Song and Women’s Musical Agency in the Middle Ages (with Anna Grau). I can be reached at lisa.colton@liverpool.ac.uk