Carrie Jacobs-Bond’s most successful song, “A Perfect Day,” arguably the greatest overlooked song of the 20

Sales of “A Perfect Day” in sheet music grew quickly and then held steady year after year. In the year between February 1914 and January 1915, sheet music sales of the song numbered more than 1,000,000 copies. By the end of the war more than four million copies had been sold, spurred in part by more than fifty recordings by singers such as Frances Alda, Clara Butt, and Evan Williams. No other song of the period comes close to those figures.

Newspapers in the U.S. and Great Britain report public performances throughout the war years. British newspapers from these years document how regularly “A Perfect Day” was sung up and down the country, often as a favored encore. Just in the month of November 1916 alone, newspapers record 98 performances; in December came another 108. Many of these were fund-raising events, many were hospital concerts for the wounded, and many happened in church settings, especially in Non-Conformist meetings such as Congregationalist P. S. A. gatherings (“Pleasant Sunday Afternoons”). During summers, a version for band and solo trumpet was very popular at concerts in the park, as still occurs.

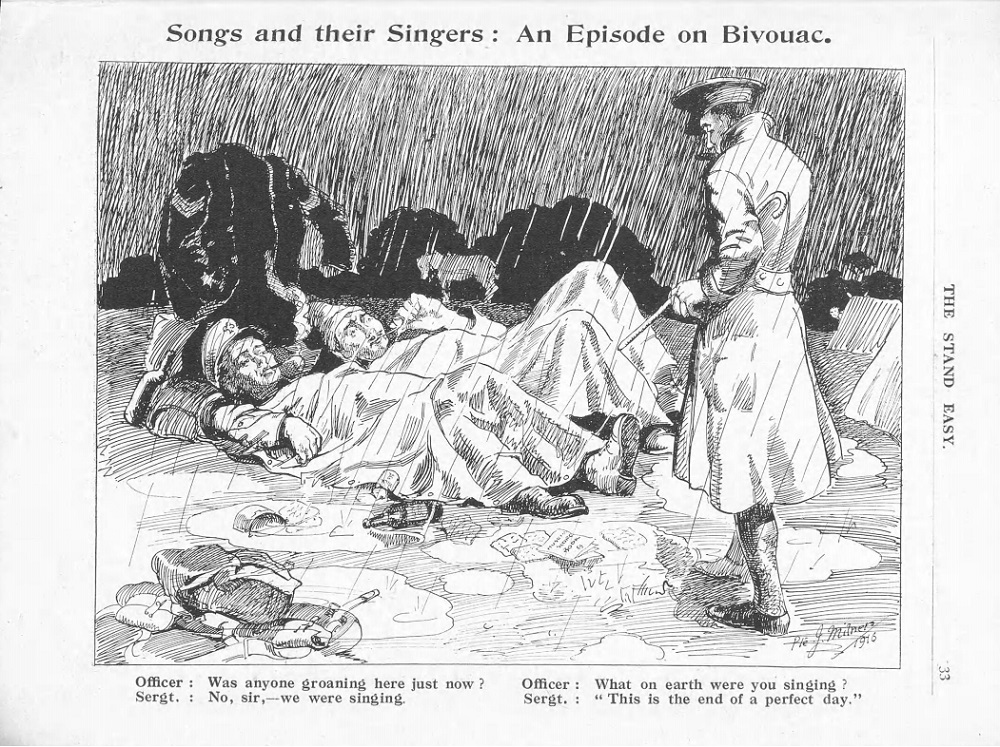

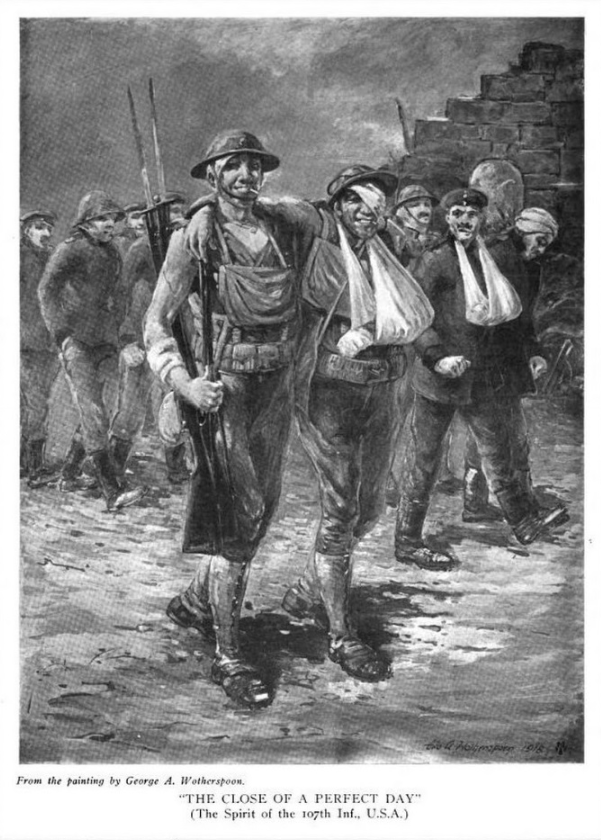

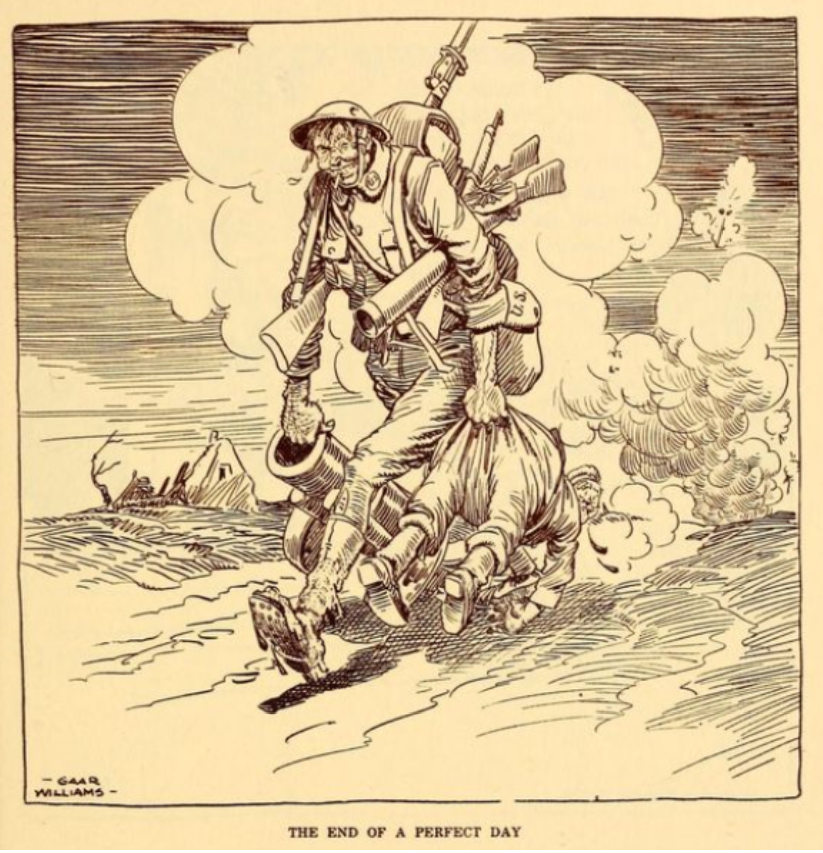

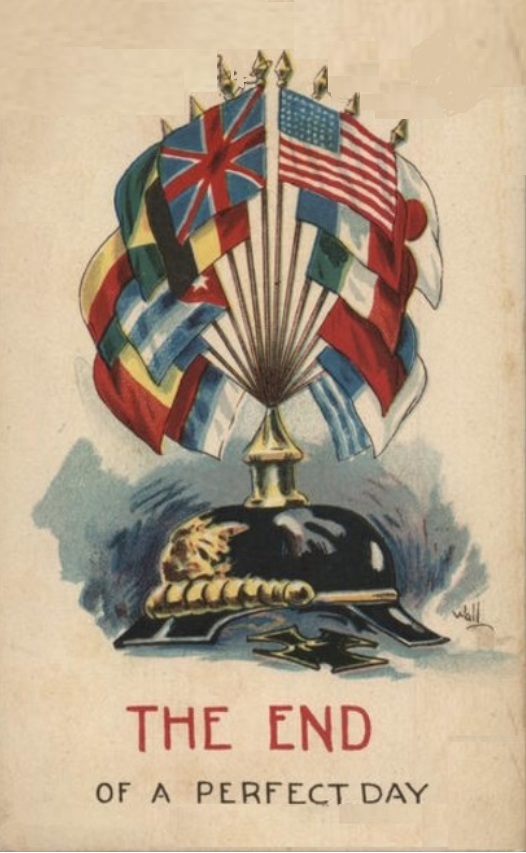

During the war “A Perfect Day” moved soldiers because it transported them home, or to friends they had lost, or because they were grateful to have survived another day. In the years after the war, it reminded them of army buddies buried in a French or Flemish war cemetery. Hundreds of cartoons from these years use the song title as a caption, and George Wotherspoon used it as the title for a painting. The nationally syndicated cartoonist, Gaar Williams, drew his iconic image of a triumphant doughboy for the Indianapolis News. It first appeared on 20 July 1918, beneath the paper’s large headline: “Huns, Repulsed, Are Retiring Across the Marne.”

The sources of the song’s power were recognized and discussed already during the war. Melody and words contributed equally, the tune hummed or whistled, the words quoted or paraphrased in letters home. In Australia the column “On Books and Authors,” published in The Adelaide Register in the last days of the war (28 Sept. 1918), captured these very sentiments:

There are few concert programmes from which this song is absent, either at home or close to the front line. At one of the latter, during a pause in the sing-song, the leader … announces that he will sing a solo. “What do you want?” he asks. Some cry “The perfect day,” and others ask for another song. “Show hands,” he cries; there are a few dozen for one, and some hundreds for the other, so “The perfect day” is sung. It is always a prime favourite, and the psychology of the song is a study. It enables the man to think of home, but the spirit of the piece saves them from any dull feeling of loneliness; the heart is wreathed in good feeling, sober and subdued, and, as they think of the home folks, they have no dread; all is well there as with themselves. It is not a song they want to sing so much as listen to, and when it is sung to the piano, and the soft compelling notes of the violin, a hush falls, and they listen without moving a muscle.

The responses to “A Perfect Day” that mattered most to Mrs. Bond were those from the many soldiers who wrote her to express their appreciation. To quote from just one:

In England, July 10, 1917 / Mrs. Carrie Jacobs-Bond: I have often thought of writing to you about the marvelous popularity of this particular song. I mean to be perfectly candid without the slightest intention of flattering you, when I say that ‘The End of a Perfect Day’ is the most popular ballad in the army of the Allies. I heard it last winter played upon a one-string violin accompanied by several quaky voices as it came from a quarantined hut; I heard a famous London singer at the Soldiers’ Recreation hut, where thousands were; I heard a cornetist, with a woefully bad band, puff and spout his way through it and receive a tremendous encore; I heard an entire battalion, coming in from the rifle ranges, sing this number as a marching song; I heard it as a duet Sunday night in a little old tent where divine services were held for such as might come. I have used the song dozens of times by request and have always found it to be enthusiastically received. / Very truly yours, Ed Chenette (Watt, 1917).

Several songs of Carrie Jacobs-Bond were the favored repertoire of a group of “four blind Tommies” who named themselves the “Shrapnel Quartet” for the injuries they had received in battle. Rather than return to England, they toured the front lines, contributing musically to the war effort. One of them wrote to Mrs. Bond, “Over here in the trenches and in the crowded hospital wards, we do not sing ‘There’ll Be a Hot Time in the Old Town Tonight,’ … we sing the song that has become the inspiration of the trenches: ‘The End of a Perfect Day’” (Anon., 1918). The 1914 recording of the Metropolitan Quartet gives us our best sense of what soldier quartets sounded like.

When the end of the war arrived, celebrating soldiers and civilians repeatedly invoked the phrase “the end of a perfect day” and the song that made it so common. The diary entry for 10 Nov. 1918 of Eddie V. Rickenbacker, the American ace fighter pilot, concluded: “Major Kirby reports getting lost and meeting a Fokker whom he shot and saw him crash. Report of Kaiser’s abdication and revolution in Germany. Indeed the end of a perfect day.” And Mrs. Bond tells of an impromptu singing of “A Perfect Day” witnessed in Manhattan by her son, Fred Smith:

On November 11th, 1918, the day the Armistice was signed, my son was in New York City, standing at the head of Central Park, when four men put their arms around each other’s waists and began marching and singing A Perfect Day. My son joined them and they gathered singing men until they landed down at Madison Square with over 5,000 in that serpentine line all singing my song. When my son telegraphed me this news I said, ‘This is the end of A Perfect Day for me’ (Bond, 584).

Notes

The Highley Colliery closed in the 1960s, but the Highley Colliery Brass Band, founded in the 1890s, lives on, reborn in 1993. There is a good post on the impact of “A Perfect Day” in Australia.

Anon., “Famous Woman Composer Sings at Syracuse,” Music Leader, vol. 36 no.16 (17 Oct. 1918), 381.

Carrie Jacobs-Bond, “Music Composition as a Field for Women. From an Interview Secured Expressly for The Etude, with the Most Successful Composer of Songs of the Present Day,” Etude Magazine (Sept. 1920), 583-84.

Charles Watt, “Carrie Jacobs-Bond: An Appreciation,” Music News, vol. 9 no. 4 (2 Nov. 1917), 20-21.