Twenty-five years ago I began my database of songs composed by women and published between 1890 and 1930 in the United States and the far-flung countries of the British Commonwealth. It has now reached the point that I can declare it done (I think!). A few days ago, I posted the tenth version of this database. After beginning with 2700 titles in 1996, the database has reached almost 24,800 entries of songs and song publications by 5148 women songwriters, nearly twice the number of women included in the previous database I posted only three years ago.

Since the last update in June 2018, I have added approximately 5000 songs and over 2400 women, the vast majority of whom published just a few songs. Of these women, more than 4000, approximately 80%, published just one, two, or three songs. In terms of the numbers of songs published, the data indicates that roughly one quarter of all songs published in English-speaking countries in these decades was composed by women who were eager to have one, two, or three songs on their own pianos. Reckoned the other way around, roughly 20% of women who published songs in these years accounted for about 75% of all publications.

If a woman published songs between the years 1890-1930, I have included all of her songs in the database, regardless of when they were written and published. This means that for women active during these decades who also wrote before 1890 (such as Louisa Gray or Mrs. Arthur Goodeve), the database lists songs published as early as the 1860s, while for those who had just begun to publish in the years before 1930 (such as Elinor Remick Warren or Mabel Wayne), there are songs listed from as late as the 1950s, 60s and 70s. For the purposes of the database, my aim has been to gain an idea of how many songs were published in the central decades, but also to make it possible to trace the individual careers of women who published during this period. The database includes children’s songs only if the composers also wrote songs for adults. Because the database accounts for where a song was published rather than the nationality of the composer, it includes a few composers like Cecile Chaminade, who published substantially in London and in the United States, and Maria Grever, who lived and worked for many years in New York City.

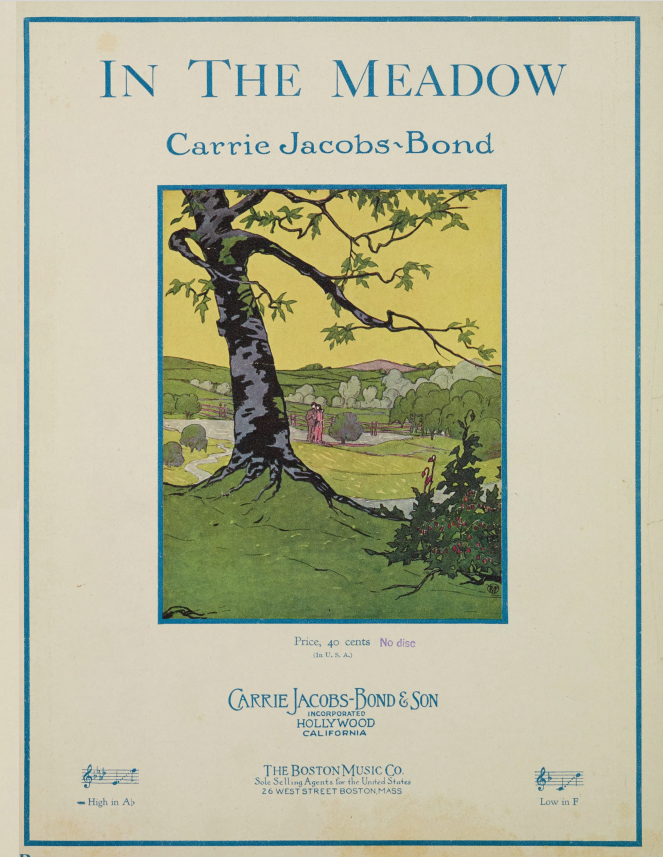

The information in the database includes title, composer, poet, publisher, date of publication, primary nationality of the composer, and the number of entries (to facilitate creating rankings of composers by the number of their publications). Further, two new columns include the city of publication and an indication of whether the song was self-published (S), issued by a publishing company (C), or a combination of those, by several women who, like Carrie Jacobs Bond, founded a company to publish their own songs (SC). There are more details in the introductory essay that accompanies the database.

My Collection

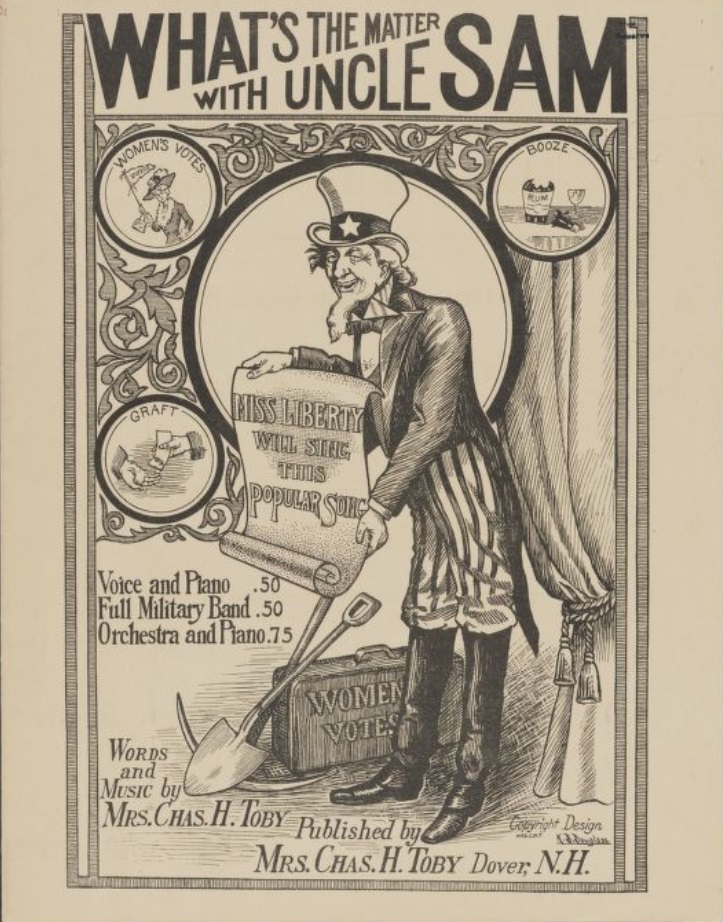

The database began as a means for me to keep track of songs I was acquiring for my collection, as a way to help me avoid buying duplicate (in some cases triplicate) copies of songs I had already purchased. But it soon began to serve a broader purpose. Sometime after the stacks of songs in my study passed the 1000-song threshold, I was curious what percentage of songs published by women my collection might represent. The expanding database soon enough revealed something I had never suspected: the astonishing number of songs published by women during these four decades needed to be measured not in the hundreds or thousands, but in the tens of thousands. For a woman to write songs and publish them – occasionally, at least in the United States, by themselves – was not at all unusual. Perhaps the comparable activity today is YouTube uploads of original songs.

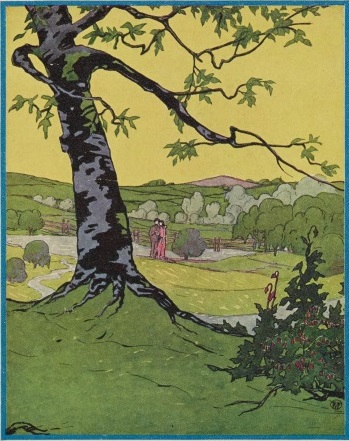

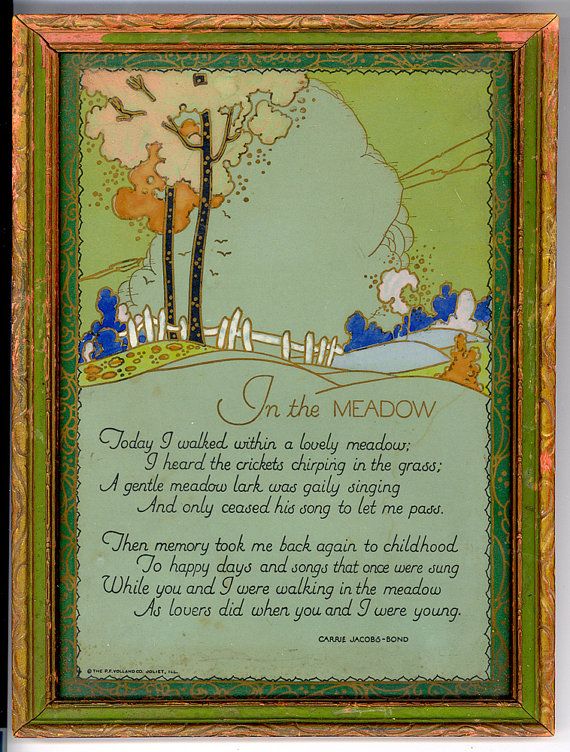

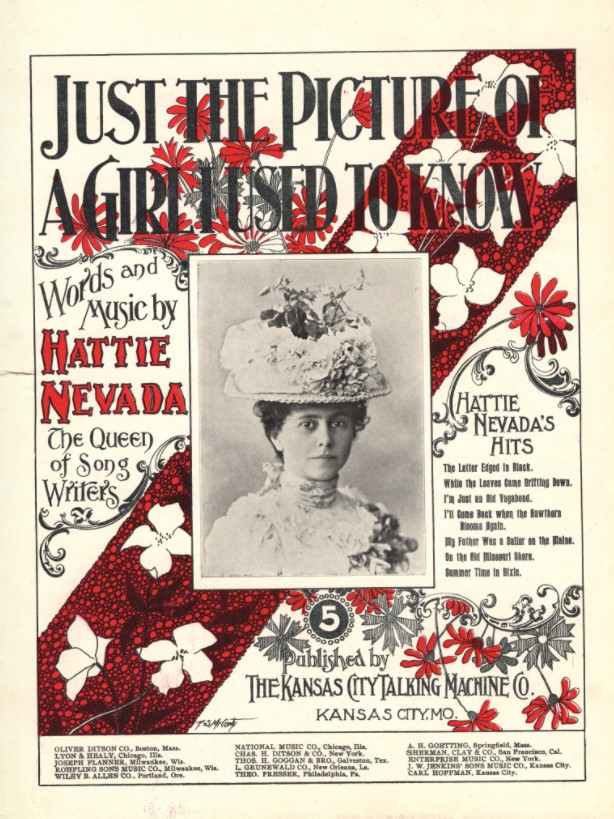

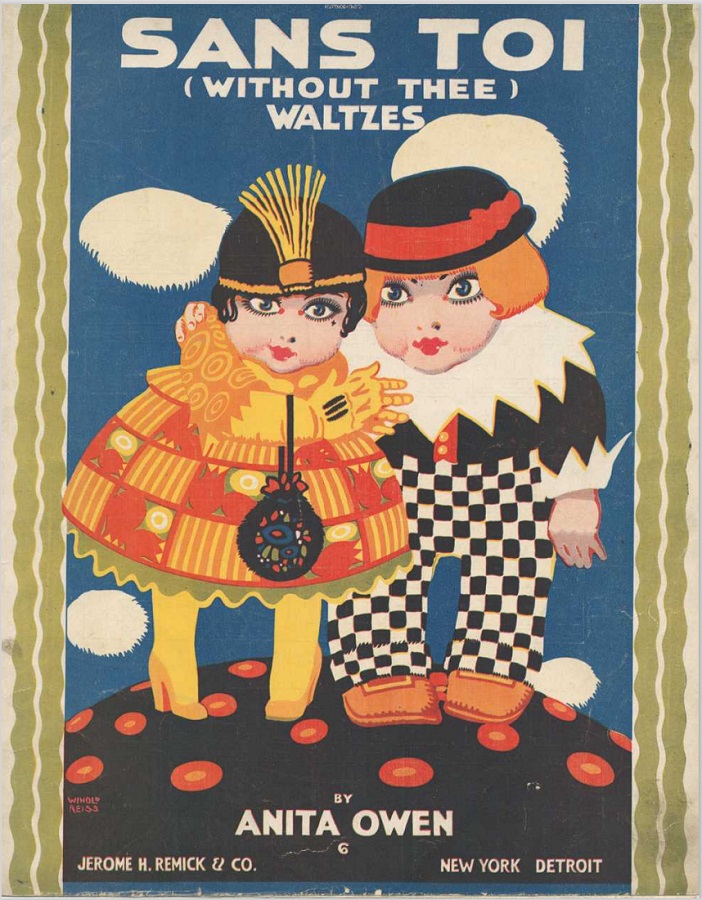

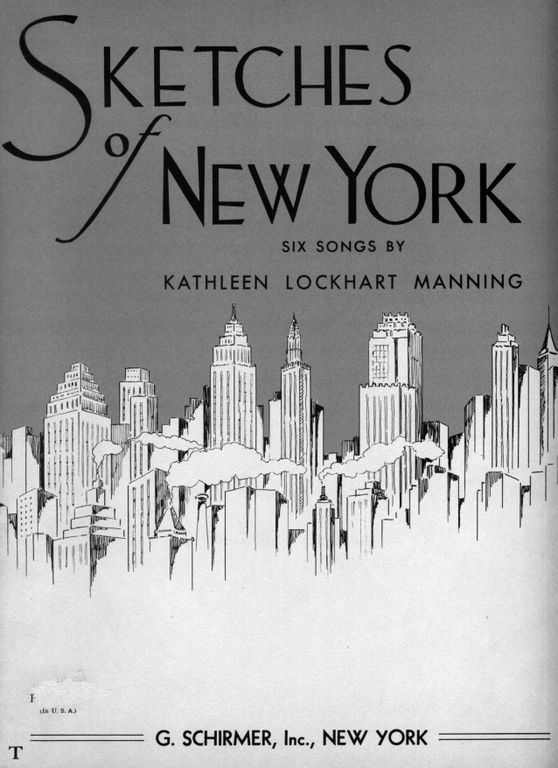

My collection now holds about 6900 songs and song publications, some 5100 of which are housed in Special Collections of Shields Library at the University of California, Davis, as the Christopher A. Reynolds Collection of Women’s Song, 1800-1950. (The pictures that illustrate this post are from the collection.) In addition to songs there are photos, many binder’s volumes, books and pamphlets, manuscripts, and 60 letters and cards from eminent women: Frances Allitsen, Carrie Jacobs-Bond, Mrs. H.H.A. Beach, Vaughn De Leath, Charlotte Sainton-Dolby, Baroness Dufferin, Virginia Gabriel, Guy d’Hardelot, Faustina Hasse Hodges, Amanda Kennedy, Julie Rivé-King, Clare Kummer, Liza Lehmann, Elizabeth Philp, Clara Rogers, Caro Roma, Ann Ronell, Avril Coleridge Taylor, Kate Vannah, Harriet Ware, Elinor Remick Warren, Maude Valerie White, and Florence Wickham.

Additionally, there are 950 letters to and from Eleanor Lee, a young Californian woman who studied voice in New York City and Schroon Lake, NY, with Henry Witherspoon, Frank La Forge, and Oscar Seagle. While in New York she lived with the young composer and pianist, Elinor Remick Warren. The letters were mostly written between 1916 and 1920. She taught voice at the University of Oregon (1918-19) and then Pomona (1920-23) until she married. Eleanor Lee was my maternal grandmother. A finding aid for the collection is available.

For an essay suggesting ways in which this database can be used to identify and answer questions about women songwriters, see my article: “Documenting the Zenith of Women Song Composers: A Database of Songs Published in the United States and the British Commonwealth, ca. 1890-1930.” In 2015 I posted a follow-up essay on the AMS blog Musicology Now.