Chen Yi has a special affection for the voice of mezzo soprano. She imagines her songs with a mezzo vocal tessitura—the rich, smooth, dark, thick and velvety sound. It is thus interesting to learn of her composing such a song in the dim, dark ambience and standstill atmosphere of a 16-hour trans-Pacific flight. Chen wrote Bright Moonlight (2000) on a plane from Chicago to Hong Kong.

Bright Moonlight evokes the mood of tranquil moonlight. But the serenity gives way to sections that are highly emotive, expressing feelings of nostalgia and homesickness, as well as yearning for reconciliation and a peaceful future. It is set suitably in the tessitura of an unforced lower register and the warm-ringing top range of mezzo soprano. From the velvety voice, one finds, despite the melancholy, comfort of reassurance.

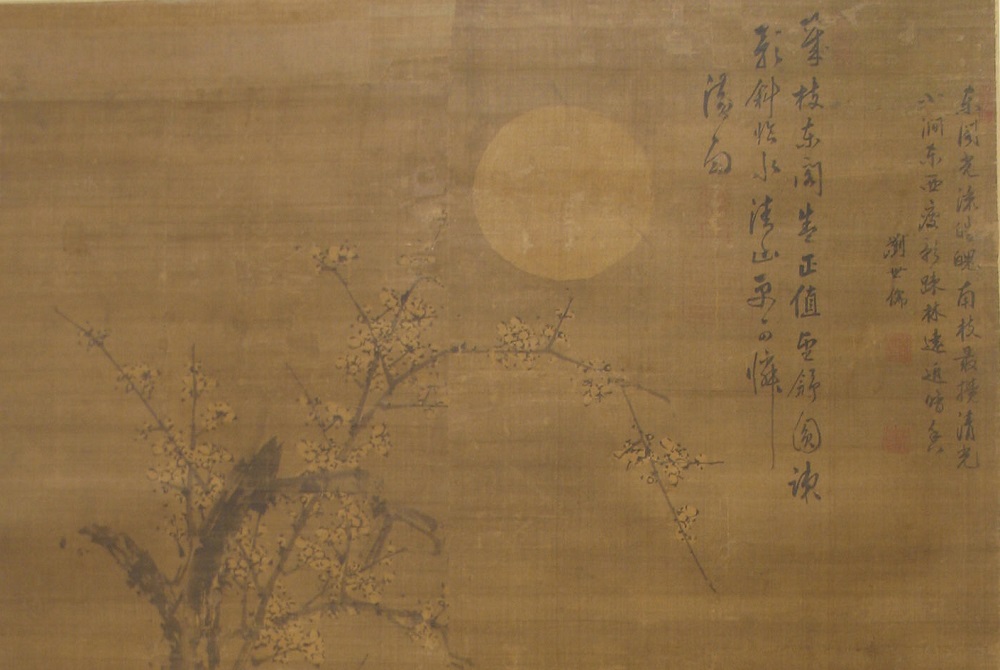

Chen Yi composed both the lyrics and music for Bright Moonlight. She drew inspiration from a poem written by the Song-dynasty poet Li Qingzhao (1084-1151), who was famous for her literary talent in her own lifetime, nine centuries ago, and has remained so up to the present day. She is often referred to as China’s greatest woman poet. Li is particularly famous for her work in the poetic genre of ci, a musical poetic genre in Chinese classic literature which some translate as a “song lyrics form.” Whereas many genres of Chinese classic poetry consist of verses in the same length (either 5-word verse or 7-word verse), ci is different. It uses a set of poetic meters with a certain pattern of rhyme, tone, rhythm and verses of varied lengths. Each set of poetic meters is associated with a tune, which is identified by a tune title. A poet chose a tune title and composed a poem to the melody accordingly. (The origin of this literary genre was indeed popular song.) There were about 800 such tune titles. Today, only the verses and tune titles remain, the melodies have been lost. Ci was the most popular poetic form of the Song Dynasty.

The Poem

The following reproduces Li Qingzhao’s poem. It was written to the tune title “Picking Mulberry.” Chen set this poem previously in a choral work, Three Poems from the Song dynasty (1995). The translation is by Ronald Egan.

采桑子 李清照

窗前誰種芭蕉樹?

蔭滿中庭,

蔭滿中庭,

愁損離人,

舒卷有餘情。

傷心枕上三更雨,

點滴淒清,

點滴淒清,

葉葉心心,

不慣起來聽。

Picking Mulberry by Li Qingzhao

Who planted a banana tree in front of the window? Its shade fills the central courtyard,

Its shade fills the central courtyard.

Leaf after leaf, heart after heart,

Folding and unfolding with an excess of feeling.

Despondent, midnight rains heard from my pillow. Dripping, a steady downpour,

Dripping, a steady downpour,

Overwhelms a northerner with sadness

Who’s not accustomed, sitting up, to hearing this sound.

This poem has two stanzas, with the second verse of each stanza repeated. It expresses an emotional distress, and invokes a strong feeling of displacement, which resulted from Li and her beloved husband’s relocation to the south owing to the political and military turmoil of the Northern Song. The poem depicts a sense of displacement by referring to the sound of rain dripping on the broad leaves of banana trees, a plant of the warmer climate in the south, a sound northerners were unaccustomed to hearing. Both the tree and this sound are foreign to the listener, who is displaced from her native land. Particularly effective in the poem is the repetition of the second verses in both stanzas. By repeating they reinforce the images—layers of shade and steady stream of dripping rain—thus adding intensity to the agitated mood, the cause of which is only revealed in the last verse.

Chen wrote her lyrics following the lyric form of Li Qingzhao’s poem, using the repetition to similarly expressive aim. As a whole Bright Moonlight resonates with the sense of displacement expressed so gracefully in Li’s poem. It also conveys a sense of melancholy, the internal disorientation. An important difference is that, instead of the sense of distress in Li’s poem, Chen uses the symbol of bright moonlight to create a more promising outlook. A full moon, which the bright moonlight suggests, is a traditional Chinese symbol of peace, prosperity, and family reunion. With the imagery of bright moonlight, a contrast to the disagreeable banana tree and shade, Chen introduces a spirit of optimism in her lyrics, at the same time paying tribute to Li Qingzhao’s poem about nostalgia and displacement.

Bright Moonlight (2000) by Chen Yi

Outside my window bright moonlight

Kissing the grassland,

Kissing the grassland,

Near in front, far away

Given to the earth with consonance

Look at the window bright moonlight

Missing my homeland,

Missing my homeland,

Near in front, far away

Yearning for the world of consonance.

Chen’s Setting of the Poem

Chen brings attention to the distinctive feature of repetition both visually and sonically. In the program note for the published score, the lyrics are presented in a layout to convey the lyric form. Each of the poem’s two stanzas is enclosed by an opening verse and concluding verse, both of which connect to the exterior world. The stanza’s inner verses turn to personal emotion, expressing the interior sensibility. These inner verses are padded with repetition to intensify their effect. The intensified effect of these verses is further reinforced in the song, where the vocalist sings “Near in front, far away” three times in the first stanza, and four times in the second stanza. The culmination from the repetition leads to a climax at the penultimate verse of the poem, where the verse “Near in front, far away” is being repeated a fourth time, with its last note reaching and sustaining on the highest pitch of the song’s vocal melody.

Many lyrical melodic lines in Bright Moonlight are composed to emulate a singing style characteristic of the vocal delivery in Peking Opera. It is the long, drawn-out syllables with melismatic passage that emphasize individual words or phrases in a melody. The Chinese term for this singing technique is 拖腔, which literally means “hold tone.” Notice in particular the word “grassland” in its second appearance. A kind of a curving up, pulling down and again pushing up to a close. The type of emphatic rendering of a melodic phrase so integral to the vocal style of Peking opera is used effectively in many vocal lines of the song. They provide a sense of fluidity and the feel of richness to the otherwise brief and straightforward verses. Even though sung in English, with the inspired melisma and drawn-out long phrases, the vocal line seemingly alludes to the intricacy of linguistic attributes of Chinese.

The expressive effect of Bright Moonlight also owes in large part to the dramatic complexity of piano writing. At the opening the 7-note ostinato and soft tremolo in the highest register create a beautiful tapestry, setting a quiet and tranquil mood of the night. When the piano leaves the high register, traversing in expressive single notes across six octaves in a dip into the lowest register, the song enters the poet-singer’s interior world, the disorientation and sense of displacement. The dark sonority of the piano in the low register sounds lonely in the imagined darkness of the night. The first full sounding of the piano with both high and low ends of the register is reserved for the dramatic outburst of “Missing my homeland,” sung the third time. After the singer drops down to the low note on “land” and sustains, the piano continues the darkness of melancholy with its full range of pianistic sonority conveying a sense of agony. Still, optimism is the only way. The song ends with a hopeful mood, returning to the 7-note ostinato and soft tremolo in the highest register at the end, and to the bright moonlight that blankets a tranquil night.

Jetting across the Pacific must characterize the busy life of Chen Yi, who is a highly regarded and sought-after composer on both sides of the ocean. Her accolades include the Charles Ives Living Award, elected member of American Academy of Arts and Letters, as well as the China Education Ministry’s Cheongkong Distinguished Scholar. A composer with what Edward Said calls, “a plurality of vision,” and with multiple places she calls home, Chen’s work often conveys deep longing and nostalgia, yet never dismay.

There can be no better image of such genuine optimism than the bright moonlight: Looking out the window to the bright moonlight in melancholy, and hoping to be soothed by the sight of the fullness of the moon that is an emblem of peace and togetherness. And it is not hard to picture Chen Yi, in the dim cabin of an airplane, distilling her sonic imaginary with the warm, thick, and velvety mezzo soprano voice, as the flight takes her across the Pacific to the land of her mother tongue.

Notes

Jennifer Bain and Nancy Rao, eds., “The Music of Chen Yi,” Music Theory Online 26.3 (2020).

Ronald Egan, The Burden of Female Talent: The Poet Li Qingzhao and Her History in China (Boston: Harvard University Asia Centre, 2014).

Leta E. Miller and J. Michele Edwards, Chen Yi (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2020).

Wen Zhang, “An Infusion of Eastern and Western Music Styles into Art Song: Introducing Two Sets of Art Song for Mezzo-Soprano by Chen Yi,” DMA thesis, University of Nevada, Las Vegas, 2012.