Portrayals of Queen Charlotte, the wife of England’s King George III, first by Helen Mirren (The Madness of King George), and more recently by Golda Roshuevel and India Ria Amarteifio (Bridgerton and its spin-off Queen Charlotte: A Bridgerton Story) have brought to life the woman at the height of English fashion in the early nineteenth century. Roshuevel, in particular, shows us many facets of a rich woman’s life circa 1800, including snuff, cards, dress, and etiquette. A fascinating addition to Charlotte’s role in the cultural life of the period would be music in her life; that is, women’s music: music for women by women. Harriett Abrams’s 1803 publication of songs dedicated to Queen Charlotte constitutes an ideal starting place for re-creating the soundscape of women’s music in the Bridgerton era.

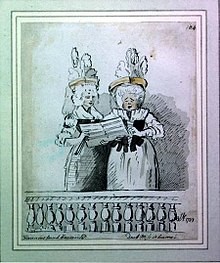

Harriett Abrams (ca. 1762-1821) belonged to a musical family of Jewish descent who lived mostly in the London area. The Biographical Dictionary of Actors, Actresses, Musicians, Dancers, Managers, and Other Personnel in London, 1660-1800 lists her as a sister of John Braham, the famous tenor, although some scholars contest this association. We are on firmer ground with her female relations: Harriett often performed with her sisters Theodosia and Eliza. A famous pencil drawing by Richard Cosway portrays Harriet on the far left and Theodosia looking at the music, and scholars have speculated the other two people to be either parents (Harriett and John), or one of the women to be Eliza and the man to be John Braham. After their successful careers in London, the three sisters spent their last years in Torquay. Only Theodosia married, but, after her husband died young, she joined her sisters in the southwest.

Abrams’s resume exposes a formidable musical talent that stretched the limits of possibilities for women in late eighteenth-century England. She studied with Thomas Arne, from whom she presumably learned composition. As a singer, she performed in London concerts, provincial festivals, Handel Commemoration concerts in Westminster Abbey, and on the stage at the Theatre Royal (Drury Lane). These activities date mostly from the 1780s. Contemporary reviews particularly praised her duets with her sister Theodosia, and Charles Burney commented on her musicianship and the sweetness of her voice. Notably, in three of her benefit concerts of the 1790s, Haydn accompanied her. In the 1790s, Abrams organized the “Ladies Concerts” held by aristocratic women. The evidence points to a considerable talent who was well respected by her peers and those above her socially, and her association with Arne, Burney, and Haydn marks her worthy of fuller consideration.

As a composer, Harriett Abrams published a number of works, mostly with Lavenu & Mitchell in London. She wrote over forty songs that have survived, including a set of Scotch Songs, two sets of Canzonettas in Italian and English for 2-4 voices (“Come, Balmy Sleep”), and other pieces for solo voice or duet. (None of the songs in the 1803 collection mentioned above is listed in the RISM catalog.) In addition to English songs, two copies of the song collection of 1803 are known to exist; one in the British Library (available online), and the other at the Forschungszentrum Musik und Gender at the Hochschule für Musik, Theater, und Medien in Hannover. Neither copy includes the title page, so we do not know the collection’s original name. Her most popular works, “Crazy Jane” and “The Ballad of William and Nancy,” have been mentioned numerous times by modern authors, but the extent of her output rarely receives much attention. Stylistically, most of Abrams’s compositions are sentimental ballads filled with drama. They attest to her knowledge of theater music, with dramatic pauses, changing moods, a variety of tempos, and vivid accompaniments that propel the music forward.

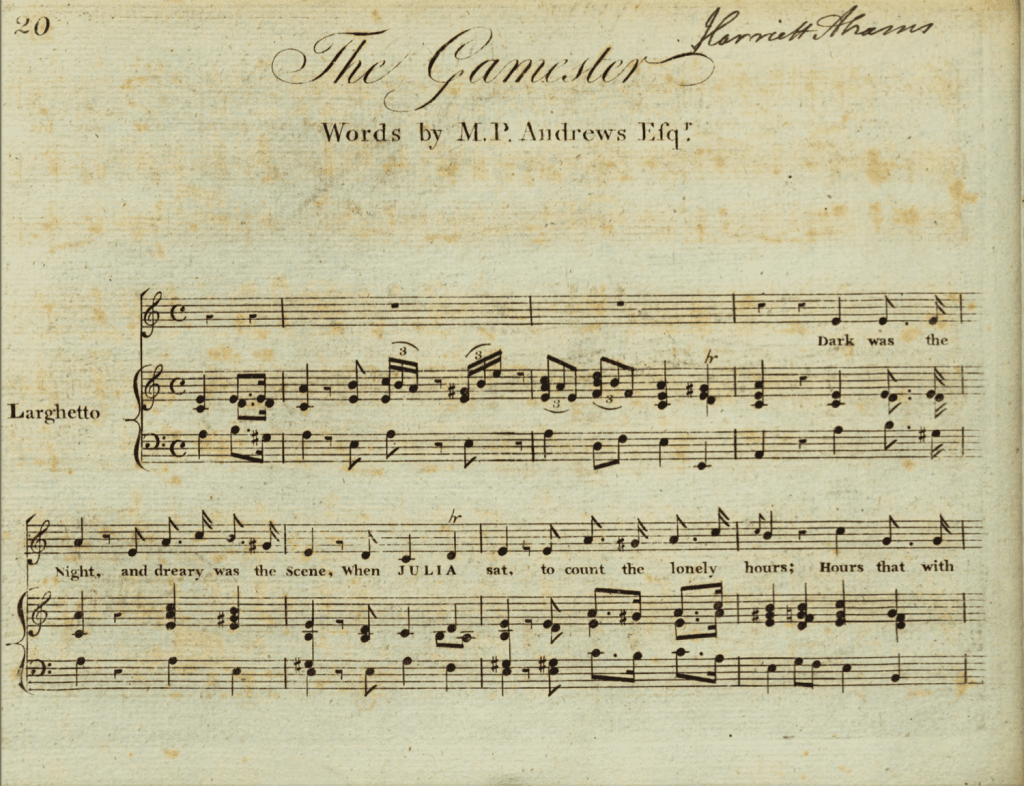

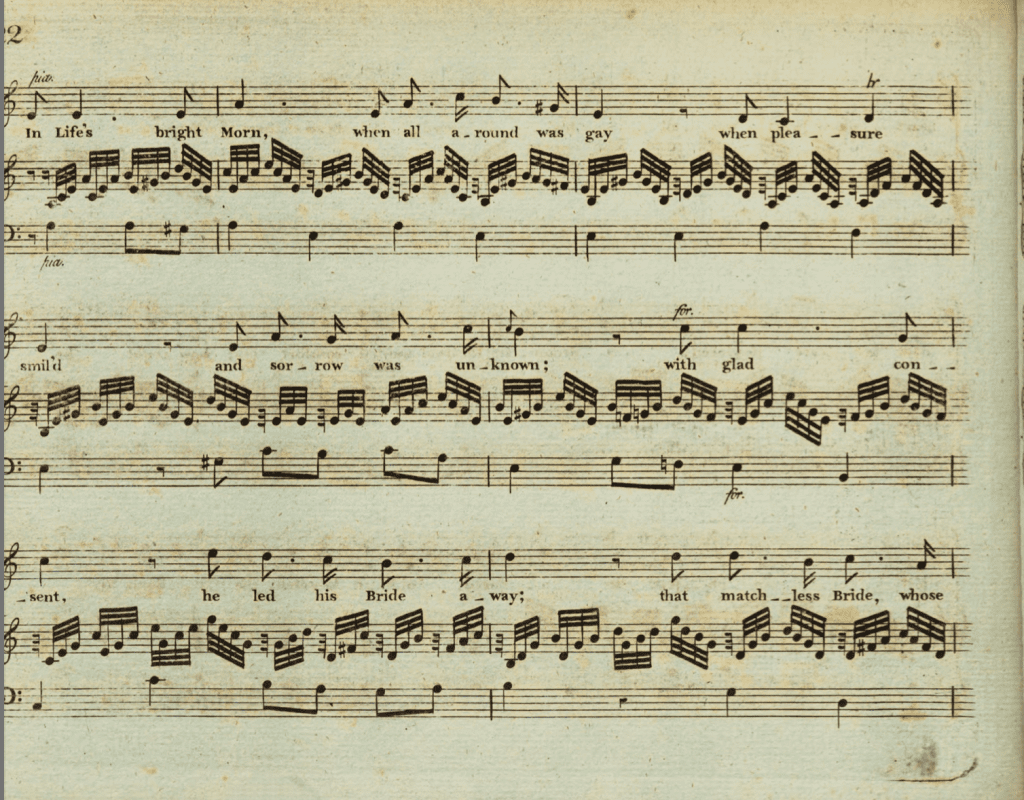

Composed not long after she ceased performing publicly, the 1803 songs include a few light-hearted love songs, two songs about immigration (including “The Emigrant’s Grave”), a somber song about death, and one concerning the woes of gambling. Interestingly, Abrams wrote out all of the accompaniments, and, in several cases, these move from verse to verse much like piano variations of the early nineteenth century, especially those associated with the London Pianoforte School. The two pages of “The Gamester” (below) illustrate how Abrams incorporated this style in her songs. Not everyone composed the accompaniments for printed songs during this period (often they would be found with only the vocal part and a bass line), and Abrams’s doing so serves as a nod to her training and associations with composers such as Haydn.

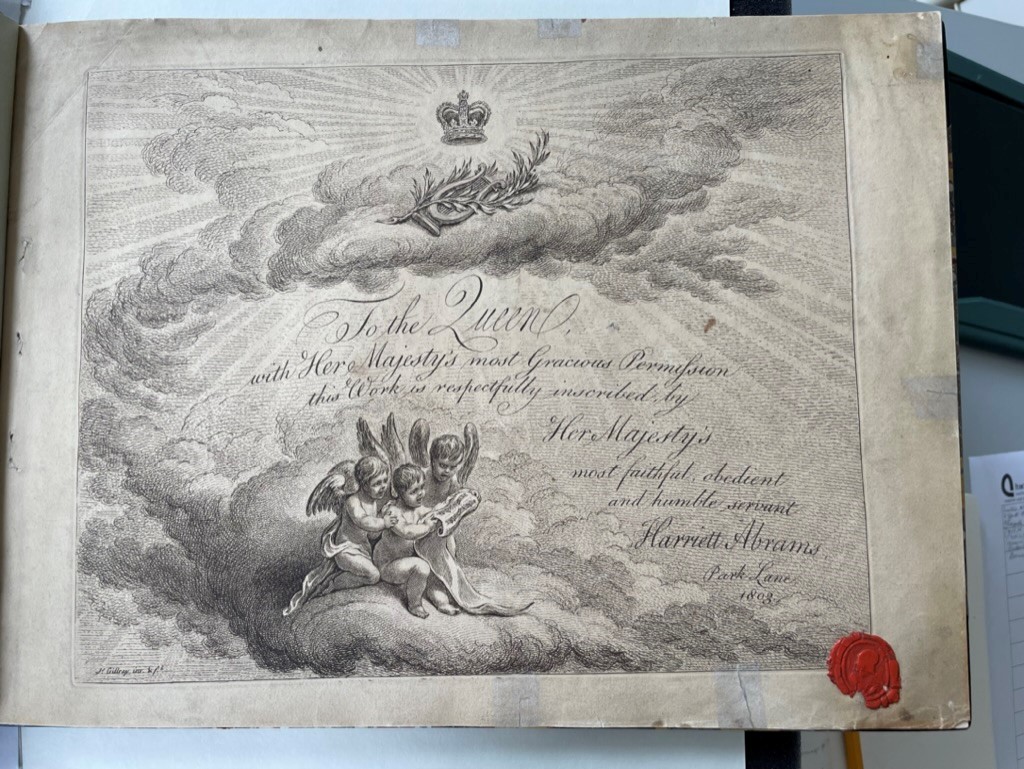

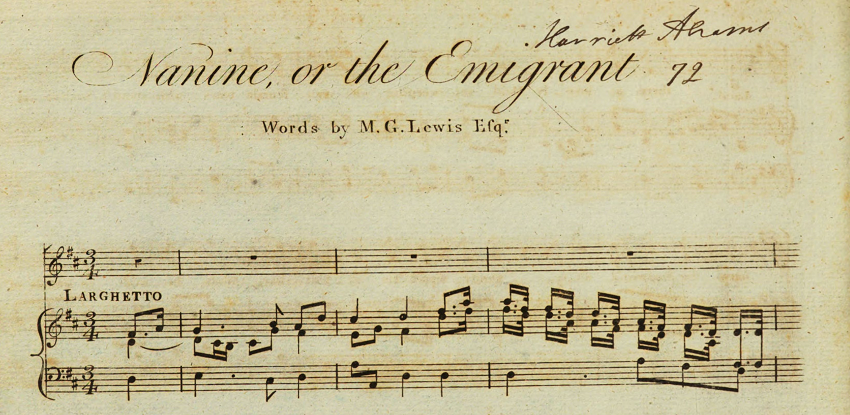

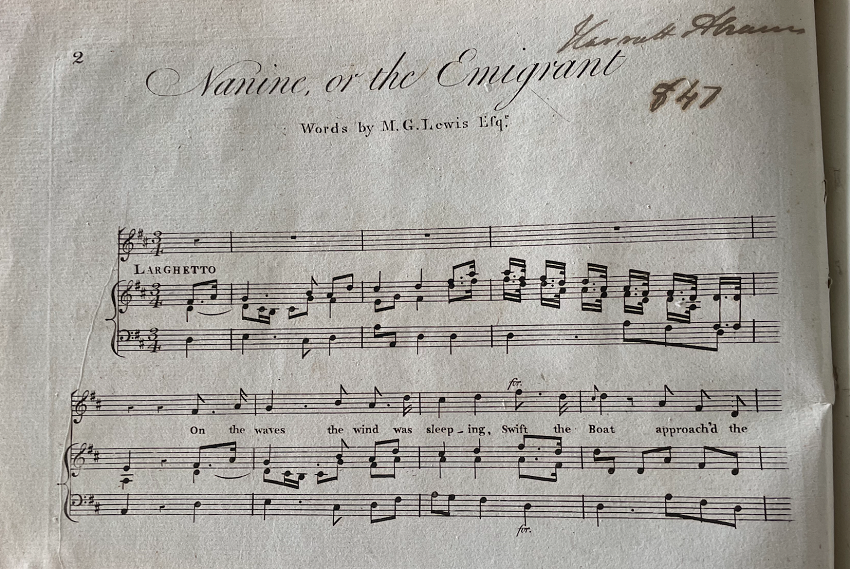

What caught my attention about this collection is that Harriett Abrams signed her name on each song. The signatures differ slightly on each page. They are not stamps. Furthermore, the signatures on both the London copy and that in Hannover vary, even on the same pieces. Additionally, the first piece has a number written on it (in both copies), which suggests that these were numbered publications. If this is indeed, correct, the Hannover copy bears the number “847,” which indicates that at least that many copies were made, even sold. The contents page claims that “all the former compositions of Miss Abrams” may be had at Lavenu’s store at 29 New Bond Street, although the Hannover copy includes “Entd at Statrs. Hall,” which is missing on the London page. This supports the notion that #847 is a later print than #72, for the earlier print had not been entered at the time of publication. Here is the London copy in the British Library:

And here is the “earlier” copy, now in Hannover, at the Forschungszentrum Musik und Gender at the Hochschule für Musik, Theater, und Medien Hannover

The act of signing her name on each piece in multiple publications screams agency – Harriett Abrams left no room for doubt as to the composer of each song in the 1803 collection. The publisher did not print her name on each composition, but that was a common practice. If we think about the industry required, such as the numerous time she dipped her pen in the inkwell or even the space where she would have sat in order to sign them all, we begin to understand an almost desperate attempt to claim her work. She wrote not only on the first piece (with its number) but on every single song. Was this in case the collection was split up? Perhaps. Whatever her reasoning, Harriett Abrams boldly claimed authorship of each title in the 1803 song collection. This gesture speaks volumes about control, reputation, and self-preservation.

Fans of Bridgerton will certainly identify Abrams’s aims with those of Lady Whistledown and Eloise Bridgerton in their nascent feminist actions. Roshuevel’s Queen Charlotte would admire her. Whether the real Queen Charlotte did remains a mystery.

Notes

Baldwin, Olive and Thelma Wilson. “Abrams, Harriett.” Grove Music Online (accessed May 2023)

Conway, David. “John Braham – From Meshorrer to Tenor.” Jewish Historical Studies 41 (2007): 37-61.

Highfill, Philip H., Kalman A. Burnim, Edward A. Langhans, eds. The Biographical Dictionary of Actors, Actresses, Musicians, Dancers, Managers, and Other Personnel in London, 1660-1800. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1984.

Joncus, Berta, and Vanessa L. Rogers, “‘United Voices Formed the Very Perfection of Harmony’: Music and the Invention of Harriett Abrams,” in Celebrity: The Idiom of a Modern Era, ed. Bärbel Czennia (New York: AMS Press, 2013), 67-106.

Ritchie, Leslie. Women Writing Music in Late Eighteenth-Century England: Social Harmony in Literature and Performance. London and New York: Routledge, 2008.

Shepherd, Polina. “Abrams, Harriett.” Jewish Music WebCenter. http://jmwc.org/abramsp-harriett/ (accessed May 2023)

Temperley, Nicholas. “London and the Piano, 1760-1860.” The Musical Times 129, no. 1744 (1988): 289-293.

Guest Blogger: Candace Bailey

Documenting how and why women made music in the past motivates almost all of my scholarship. Although my recent book, Unbinding Gentility: Women Making Music in the Nineteenth-Century South (2021), examines musical women across race and social divides in the United States, I have also worked with collections in Europe and Chile as I seek to interpret the place music holds in women’s history. I discuss some of the collections I study on my website (clbaileymusicologist.com). A larger forthcoming project is supported by the National Endowment for the Humanities.