When Italian singer Beniamino Gigli made his farewell tour of America in 1955, some three thousand people packed Carnegie Hall to hear his recitals. On April 24, in addition to operatic selections by Massenet, Puccini, and others, Gigli sang “Life” by American composer Pearl Gildersleeve Curran. This brief song had been in his repertoire for more than three decades, since at least 1923.

Robustly accompanied with surging arpeggios and crashing chords, “Life” was appropriate for an operatic tenor, allowing him to hit dramatic high notes as an expression of his “spirit’s flame” rising from “dull eclipse.” Because he was then 65 years old and suffering from diabetes and heart disease, his impassioned rendition of “Life” doubtless carried extra emotional power. Curran usually wrote the lyrics for her songs as well as the music, producing vocal showcases that were often sentimental or religious, but in this instance, “Life” was a poem by Mary Stewart Cutting. Curran composed a triumphal post World-War-I song from 1919. The “dull eclipse” of the war years had passed at last, the U.S. was on the cusp of the Roaring Twenties.

Life, come to me today! This I entreat;

Flow in my hands, inform my lagging feet;

Shine in mine eyes and smile upon my lips;

O, lift my spirit’s flame from dull eclipse!

And sing within my heart, that I may be Life,

Life in my turn for those who look to me.

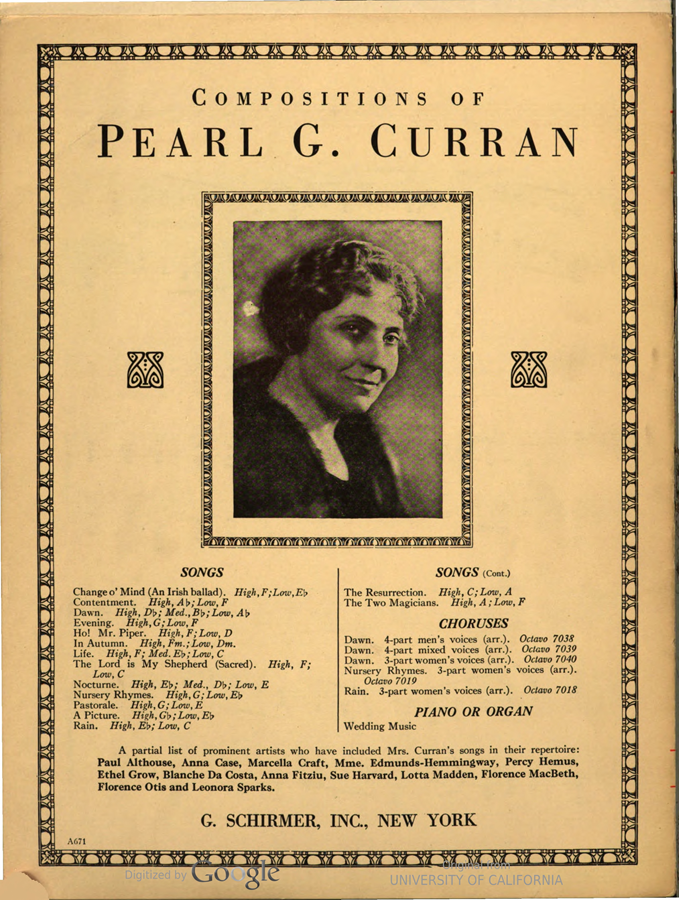

Pearl G. Curran – the middle initial was necessary to distinguish her from the Pearl Curran of paranormal fame – was born in Denver in 1875; when she was still young her family moved fifty miles from town to a sheep ranch. Pearl could retain melodies at age two and began to play the piano at four. As a child, she was attracted to the violin, holding it between her legs like a cello, but her mother found this “unladylike” and restricted her to the seemingly more feminine piano. Although Curran attended the University of Denver for nine months, she married at eighteen and gave up music for eight years. She did not begin to compose until her early thirties when her two children were older. Curran primarily produced solo songs, some of which were also made available in choral arrangements.

Curran spent most of her life in New York state. A member of the women’s Manor Club in Pelham for twenty years and head of its music section, she composed the theme song, “The Blessing,” sung regularly at its luncheons. In spite of her songs’ renown, Curran was sometimes portrayed in ways that stressed her gender over her achievements. “Why do you want to write about me?” she asked a newspaper reporter in 1935. “I am not important. Write about the songs.” And a report about Curran for a Women’s club in Wisconsin claimed that domestic life made it possible to her to create her best work: “since she does not write for money, she never publishes a composition until she herself is satisfied with it” (anon. 1940).

But another account suggests ambition and determination: Curran had “worked and worked hard for a good many years” to achieve her fame (anon. 1938). Indeed, early in her career she had sought professional assistance from fellow song composer, Fay Foster, one of the most successful women composers of her generation. And, like numerous other professional composers, Curran was a member of the National League of American Pen Women.

Operatic Performances

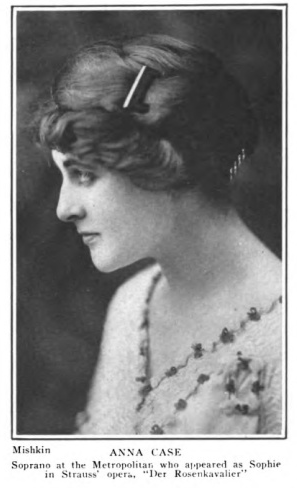

The popularity of Curran’s songs was in part due to performances by leading opera singers. Curran was reportedly “discovered” by Metropolitan Opera soprano Anna Case, playing the piano on a ship returning from Europe shortly before World War I. “Just what do you do in the musical world?” Case asked, to which Curran responded, “Oh nothing, I just play a bit.” With more than a little understatement, Case answered “Well, I sing a bit,” and the two performed together on board. One of Curran’s most popular songs, “Dawn,” was written specifically for Case. The singer premiered it at a New York recital in 1917, where it was so well received that she had to sing it twice. The song was rejected multiple times before finally appearing in print. By 1920 over ten thousand copies of “Dawn” had been published.

Curran composed “Rain” around the same time, inspired by her trip driving a disabled WWI soldier to New York City during a downpour. Case also sang “Rain,” which she often had to repeat. The soprano told Curran that she never performed her songs “without the people just coming out of their seats.”

In addition to Gigli and Case, other notable singers were attracted to Curran’s songs. Enrico Caruso gave the first performance of “Life” in Manhattan at a morning musicale at the Waldorf Astoria Hotel. In 1934, after repeating “Life” at a Budapest music festival, Moise Bulboaca had to refuse to sing it a third time. Mario Chamlee’s renditions of “Dawn” likewise received ovations, and the song was given by Lawrence Tibbett as well. Curran wrote “Nocturne” for baritone John Charles Thomas, who premiered it in 1922 and recorded it for Brunswick Records. Fourteen years later he sang it for an audience of 5000 in a concert at New York City’s Lewiston Stadium.

Performances by Women Amateurs

In spite of multiple performances and recordings by men, Curran’s songs were most often programmed by women at club events. Even with her relatively small output, Curran was one of the most frequently heard composers on the American women composers’ concerts organized by clubs in the three decades between 1920 and 1950. In addition to luxurious harmonies and vocal lines that required more than amateur skills, her songs had substantial accompaniments that appealed to pianists. One critic called “Rain” “really a piano solo with voice obligato.” Curran often played the accompaniments herself, including on a national radio broadcast, “A Half Hour with Pearl Curran.”

Some of the songs programmed by women were those inspired by Curran’s children and grandchildren. A sweetly rocking lullaby, “Sonny Boy,” which recalls her son, still allows the singer some characteristic high notes. Two less difficult selections, “Ho, Mr. Piper” and “Nursery Rhymes,” are currently sold by Hal Leonard in a collection entitled, Daffodils, Violets & Snowflakes: 24 Classical Songs for Young Women, Ages Ten to Mid-Teens, a title that suggests gender stereotypes remain a century later. Multiple YouTube videos feature girls’ performances of both songs, often as part of the publisher’s online vocal competition and sometimes sung with its pre-recorded accompaniment. You can listen to “Sonny Boy,” performed by Olive Kline (soprano), Francis J. Lapitino (harp), and Rosario Bourdon (conductor) here.

Curran’s religious songs are still performed in church settings, and not just in the United States. In 1939 “Hold Thou My Hand” was anthologized in G. Schirmer’s Fifty-Two Sacred Songs You Like to Sing and more recently appeared in a collection entitled Exaltation: Songs of Women issued in 2006 by the United Methodist Church. Soprano Gloria Ewurabena Yawson sang it on the Winneba Youth Choir’s Christmas concert in Ghana the same year. While the songs that male opera singers had selected brought Curran recognition during her lifetime are largely forgotten, the works that more clearly stereotype her as a woman composer, religious songs or works for younger singers, continue to be heard.

Notes

There is a previous WSF post about the enduring popularity of sacred songs by E. L. Ashford elsewhere in the world today.

Anon. 1938, “Pearl Curran, Composer, Gives Her Summer to ‘Keeping Cool.’” The Daily Times [Mamaroneck, NY] (23 Aug. 1938).

Anon. 1940, “Eastwin Homemakers Club, Guest of Woman’s Club, Hears Talk on American Women in Music.” Herald-Times Reporter [Two Rivers, WI] (3 May 1940).

Judith E. Carman, William K. Gaeddert, and Rita M. Resch, Art Song in the United States, 1759‑1999 (4th ed. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press, 2013).

“Curran, Pearl Gildersleeve,” in National Cyclopaedia of American Biography (New York: J.T. White, 1971), vol. 53, 557.

Marjorie Dillon, “Pearl Curran, Composer of Pelham, Inspiration of Many Great Singers,” Mount Vernon [New York] Argus (19 April 1935).

Roberta Radcliffe, “A Maker of Songs: Successful Writer of Refrains Gives Tips,” Record-Journal [Meriden, CT] (29 Jan. 1929).

Mrs. F. S. [Linda] Wardwell, American Music: Autobiographical Sketches and Music for Programs (2nd ed. Stamford, CT: n.p., 1920).