A couple of years ago, in two blog posts, I raised the possibility that a woman composer’s decision to set poems by a woman poet had several implications, including their choice of musical style and the stage of their career. For the information necessary to undertake this project, I drew on my database of women composers from English-speaking countries who published songs between 1890 and 1930, a database that today includes more than 26,000 songs by more than 5600 women.

In this post I would like to review some of my findings and then expand the circle to include German-speaking women composers for the same decades. When I started down this new path, I anticipated finding that male poets would play a larger role – this is, after all, the culture of Goethe, Heine, Rückert, Tieck, and many other revered poets. Yet German-speaking feminists also asserted themselves in the decades before and after 1900, and women poets inspired at least a few women composers. While my opening assumptions were not completely wrong, there were some surprises.

* * * *

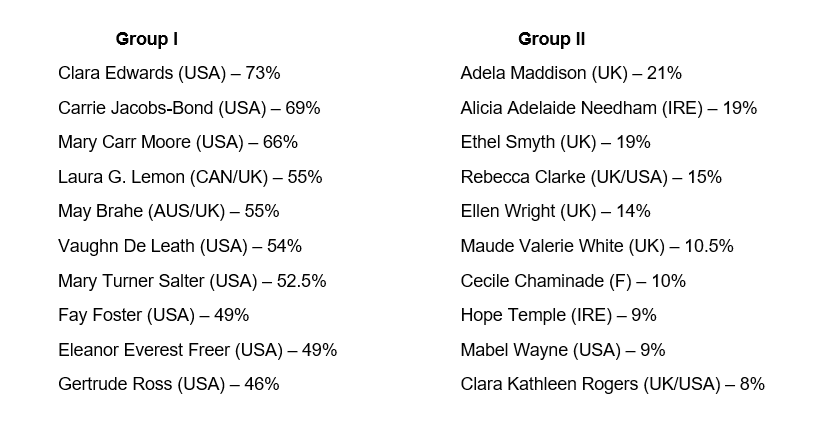

In my earlier posts exploring which women composers set women poets (and who avoided them), I first calculated the number of songs women composed to women’s poems as a percentage of their total number of published songs. I excluded from this calculation women who wrote both words and music for all or nearly all of their songs. This group primarily consists of Americans who lived in Manhattan or Los Angeles, women who were mostly involved in musicals or films.

Americans also dominate the group of women who frequently set women poets. Among the top ten, only two had careers in England, but neither was British; Laura Lemon was Canadian, raised in Winnipeg, May Brahe was Australian. Long after World War I, these women composed tonal music, writing in a style that is often called middlebrow, or light classical. They avoided dissonance, and, excepting Vaughn De Leath, also the influences of ragtime and jazz. The poems they set had rhyming verses and conveyed messages of love, comfort, home, and the wonders of nature.

How different the group of women composers at the other end of the spectrum! Obvious points of difference include geography, generation, and stature as composers of orchestral music and operas. Among those who seldom set poems by women, only three were American, and of those, Rebecca Clarke and Clara Rogers were born and raised in England (Chaminade belongs in my database, and in this calculation, because of her immense popularity in English-speaking countries). Today these are the women who are far more familiar to singers and scholars.

This second, male-oriented group is also the more senior. Six were born in the 1840s and 50s. In contrast, of those who often set women’s verses, only four were born before 1870. The approximately twenty years that separate these two groups mean that the younger women matured in the 1890s and early 1900s, the same decades that women’s clubs proliferated across the United States. From coast to coast, these clubs provided platforms for community leaders, writers, composers, and performers, creating opportunities for these diverse women to get to know each other’s work. Many of these older women were born into upper-class families and studied with illustrious teachers, often in Europe. They aspired to the kinds of musical careers then reserved for men.

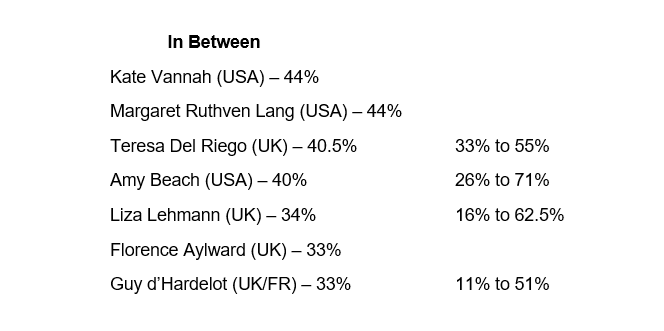

Between these two groups are seven of the most successful women composers from the period, three Americans and four Brits who were contemporaries. In this group at least one-third of their published songs set women’s lyrics. Remarkably, four of these exceptional women underwent mid-career poetic conversions, each when they were in their forties. Liza Lehmann, Guy d’Hardelot, Amy Beach, and Teresa Del Riego – all replaced a decades-long preference for men poets with one for women.

* * * *

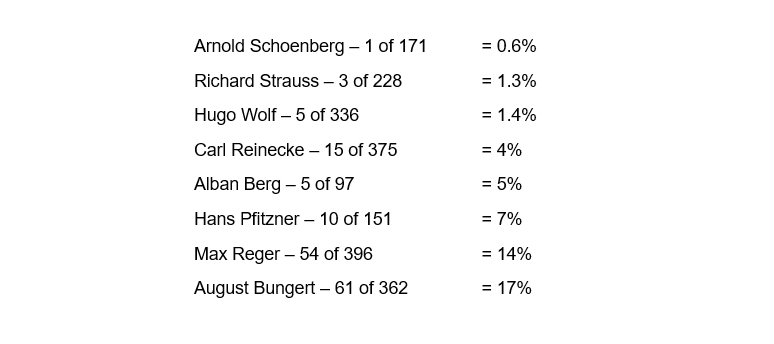

In their selection of poetry to set, the responses of German-speaking women composers are much like those of British women: generally, they follow the preferences of their male colleagues. Not surprisingly, few men of these generations composed songs to poems by women. Mahler set none. Of Schoenberg’s many songs, only one expresses the words of a woman. Richard Strauss, as extraordinary as he was in writing for women’s singing voices, showed no interest in expressing what they actually had to say. Nor did Wolf. Marginally better were Reinecke, Berg, and Pfitzner. Reger and Bungert loom as exceptions in this regard, although Bungert can be discounted. The vast majority of his songs, 57 of them, set poems by Carmen Sylva, the pseudonym of his patron, Elisabeth Pauline Ottilie Luise zu Wied, Queen of Romania.

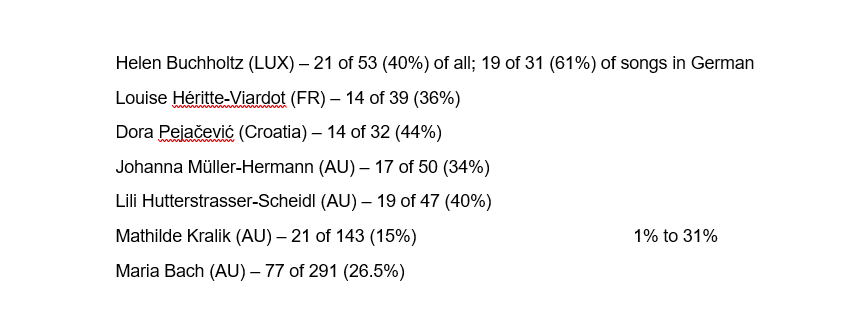

In these decades the German-speaking women composers who avoided women’s poems include, Ingeborg von Bronsart from Sweden, and four Germans: Luise Adolpha Le Beau, Clara Faisst, Ilse Fromm-Michaels, and Adele aus der Ohe. I did not expect to discover that the women who set a significant percentage of poems by German-speaking women were actually not from Germany. Here are the top seven:

Helen Buchholtz, from Luxembourg, composed Luxembourgish songs, French chansons, and 31 German Lieder. While all of the Luxembourgish songs have poems by men, well over half of those in German have verses by women. She preferred Anna Ritter over all others, setting thirteen of her poems, as did Louise Héritte-Viardot. The Croatian Dora Pejačević composed fourteen songs on poems by women. Her feminist sensibilities are evident in a letter she wrote to her husband a few months before dying in childbirth, when she urged him to treat a daughter no differently than a son: “… dependence on parents and relatives crushes many talents … therefore treat them equally, whether it be a girl or a boy.” Pejačević set Anna Ritter’s poem “Wie ein Rausch,” which is performed here by Mandy Fredrich, soprano, and Matthias Samuil, piano. (A recording of Buchholtz’s setting of this poem is also available.)

The other four were all Austrian, all residents of Vienna: Johanna Müller-Hermann’s songs for solo voice include seventeen that set lyrics by women; and her Symphonie in D Major for Soloists, Choir and Orchestra, op. 27, set a text by Ricarda Huch. Lili Hutterstrasser-Scheidl published nineteen songs by women under the pseudonym Lio Hans. Additionally, two of her six stage works have libretti by women. And Maria Bach, perhaps because she was the youngest, born in 1896, was always receptive, setting poetry by fourteen different women. Here is Müller-Hermann’s song, “Wie eine Vollmondnacht,” op. 20, no. 4, composed about 1920, performed by Kitty Whately, mezzo-soprano, and Joseph Middleton, piano.

Then there was Mathilde Kralik, whose career suggests that she, like Amy Beach and Liza Lehmann, only recognized the value of poetry by women later in life, although her awakening came near the end of her career when she was 67, rather than in the middle decades. Across her whole career, her preference for poetry by men is clear: just 21 of her songs featured women poets. But, through 1924 she rivalled Arnold Schoenberg for her whole-hearted embrace of men. Only one of the 79 songs she had published used words by a woman, and that was a poem she had written herself. Then in her remaining years, something changed. After 1924 there were twenty of 64. As with Amy Beach, I suspect that personal friendships played an important role. She chose seven poems by Adrienne Sarold and four by Anna Kann, poets who no other composer selected. Similarly, among men poets that she set, her brother Richard von Kralik wrote the vast majority. Soprano Alice Fuder, and pianist, Clemens Müller, perform her “Weihnachtslied,” with a poem by Anna Kann.

These women had ambitions to match the artistic achievements of the best composers of their time. Kralik was a pupil of Anton Bruckner, Johanna Hermann of Zemlinsky and Franz Schmidt. Maria Bach had music lessons from early childhood that culminated in six years at the Vienna Academy of Music. Though she was largely self-taught, Pejačević produced the first piano concerto and the first symphony ever composed by a Croatian, male or female. Hutterstrasser-Scheidl’s opera Maria von Magdala was the first opera by a woman ever staged in a major Viennese theatre.

* * * *

Did it matter to women who composed songs whether the poems they set were written by a man or a woman? The statistics discussed above suggest a partial answer: for English-speaking women, the gender of the poet evidently mattered sometimes. At the male-oriented end of the poetic spectrum, women such as Smyth and Clarke had high aspirations as composers of modern art music; those at the other – Edwards, Jacobs-Bond, and Brahe – were ambitious songwriters who aimed to reach broad, primarily middle-class audiences. Education, social standing, generation, and geography all matter. But in this respect the situation with German-speaking women differs. I see few stylistic differences between women who composed songs on poems by women and those who did not. Moreover, these women were far less active commercially; a larger percentage of their songs remained unpublished during their lifetimes.

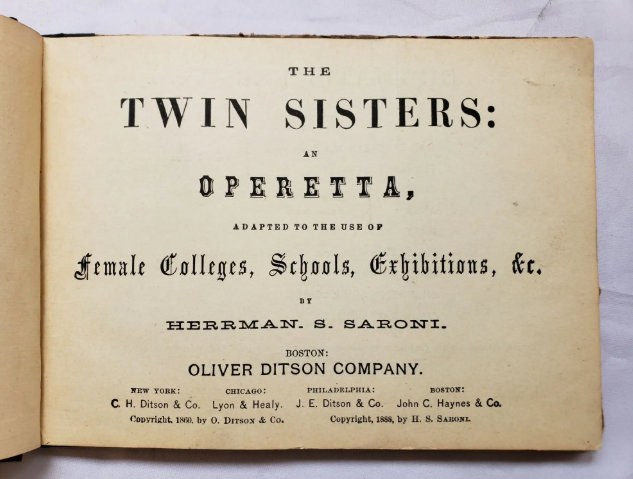

There are several possible factors at play between the different nations and generations. American women’s clubs, which proliferated in the 1890s and flourished for several decades, certainly had an impact. These clubs brought together talented women in all of the arts and a variety of professions. And American women’s colleges mounted a student musical every year, in the process training young women musicians, poets and playwrights, not only in their individual crafts, but also in the practice of creating art with other women.

The data for English-speaking women show that the women composers who embraced women poets are also those who enjoyed the most commercial success. One sign of that success is that several men chose female pseudonyms to publish their songs, something that I have not discovered in Germany. I have yet to identify a comparable group of German-speaking women songwriters who wrote popular music, or music for the theater, or for musically unsophisticated amateurs. Is that because the market for popular songs in German-speaking countries was closed to women composers? Or because the average level of musical literacy was much higher and therefore encouraged composers to follow in the footsteps of Schumann, Brahms and Wolf? One possible exception is Elsa Laura von Wolzogen, active in one of the first cabarets in Germany, the Buntes Theater in Berlin.

How then might one explain the difference between women in Germany and women in other countries? It may matter that the women from Vienna and other countries were either aristocratic or from very wealthy families. Maria Bach was a Baroness, Pejačević a Countess. Kralik’s father was a Bohemian industrialist, and Müller-Hermann’s father was a high official in the Austrian Ministry of Culture and Education. And Louise Héritte-Viardot was the daughter of Pauline Viardot-Garcia and a wealthy diplomat.

But there were other differences in what was available to women in German cities and Habsburg Vienna. Beginning in 1885, the Verein der Schriftstellerinnen und Künstlerinnen in Wien, was an interdisciplinary group that included composers as well as writers and artists. Mathilde Kralik was a founding member (Baumgartner, 132); Ricarda Huch also belonged. The counterparts in Germany all had narrower focusses, such as the Leipziger Schriftstellerinnen-Verein for writers (founded in 1890, it was the first in Germany) or the Künstlerinnenverein in Berlin for women artists and craftswomen. And in 1918 Müller-Hermann was appointed Professor of Music Theory at the New Vienna Konservatorium. Germany lagged behind all of its European neighbors in appointing women to university teaching positions (Albisetti, 299).

Yet even without the support of American women’s clubs, Lehmann, d’Hardelot, and Kralik eventually discovered inspiration in women’s words. A conservative artistic temperament arguably played a roll. Composers who continued to embrace tonality and avoid dissonance well into the 20th century were more likely to continue setting poetry with a regular meter and steady rhyme schemes. Composers who sought those traits, and also the views the poems expressed, evidently turned to women poets with greater than expected frequency. The extent to which such decisions were motivated by friendships and personal ties remains to be explored, as does the impact of a broader desire to promote the efforts of women.

Notes

This post is an English-language revision of my talk, “Frauen vertonen Frauen: Die Bedeutung von Dichterinnen für Komponistinnen zwischen 1880 und 1940,” presented at the Symposium – “her*hits: Liedkomponistinnen. Gesucht, gehört, gefeiert,” at the Forschungszentrum Musik und Gender, Hochschule für Musik, Theater und Medien Hannover (11 June 2025).

The banner photo is of Johanna Müller-Hermann by Georg Fayer, from the Bildnisalbum zur Beethoven-Zentenarfeier (1927) in the Musiksammlung der Österreichishe Nationalbibliothek, signature 580555-F.MUS.

A caveat: for my posts on English-speaking composers and poets, I could rely on my database, a resource I have developed over thirty years. I have no such foundation for this discussion of German-speaking composers. There are, of course, library catalogues, and also worklists for many women on the website Musik und Gender im Internet (MUGi). But in several cases poets are identified by initials and family names, and gender is not always possible to establish. And my database deals with published songs, while German-speaking women composers were more likely to compose songs but then not publish them in their lifetimes.

James C. Albisetti, Schooling German Girls and Women: Secondary and Higher Education in the Nineteenth Century (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1988).

Marianne Baumgartner, Der Verein der Schriftstellerinnen und Künstlerinnen in Wien (Vienna: Böhlau Verlag, 2015).