The education and early career of soprano Ivanka Milojević (1881-1975) followed a familiar route of well-off middle-class women at the turn of the twentieth century. Her mother Draginja, an accomplished pianist who appeared publicly before marrying Ivanka’s father Kosta Milutinović, supported her daughter’s career in music, giving Ivanka her first piano lessons and enrolling her to study singing at the Serbian Music School in Belgrade. Upon graduation, Ivanka started her career as an elementary school teacher, then a widely accepted option for young women. In 1907 Ivanka married Miloje Milojević, a fellow student from Serbian Music School, and they moved to Munich. There Miloje studied piano, composition and conducting, while Ivanka studied singing with Bianca Bianchi (born Berta Schwartz, 1855-1947). After completing their studies in 1910, the couple returned to Belgrade. Contrary to the custom of women teaching only until getting married, and then stopping, Ivanka took a post as a singing teacher at the Serbian Music School, starting a musical career of “firsts” in the region.

Ivanka Milojević

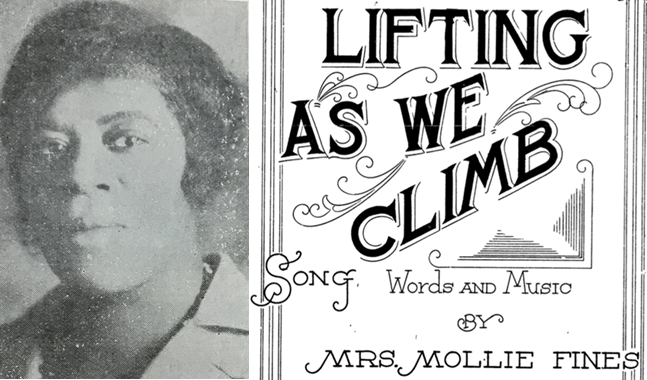

Miloje Milojević

As well as becoming an influential vocal pedagogue, she was the first professional concert singer who championed the newly composed “national” repertory. She was perceived as secondary in the artistic partnership with her husband, in part because of Miloje’s ubiquitous public role as a critic, composer, speaker and teacher. Ivanka’s avoidance of the operatic stage contributed to a dearth of written records about her. This choice was partly the result of her physiognomy: she was praised as an exceptionally refined soprano, not large in volume but warm and clear, lauded for great diction and messa di voce singing. However, her choice also suited the couple’s joint art song project, for the noble world of chamber music was, in contrast to the commercialized world of opera, an appropriate platform to present idealized ‘national’ qualities through the female voice.

Lullaby and Love Songs

The couple chose lullabies as their perfect vehicle to showcase Ivanka’s voice and express the ‘national’ identity. The result is a diverse group of songs, both original and folk song arrangements, covering a wide range of topics and emotions. Illustrating this is the couple’s recording of “Macedonian Lullaby,” its haunting sob-like grace notes and changing meter depicting conflicting emotions of a woman singing a lullaby to someone else’s baby. While titled “Macedonian Lullaby” on the record, it is called “Lulela je Jana” in the second folk-song collection that Milojević published: Miloje Milojević, Anton Neffat and Jakov Gotovac, Jugoslovenske narodne melodije (Yugoslav popular songs) (Belgrade: Collegium Musicum, 1939). He dedicated it to his wife: “To my wife Ivanka, an unsurpassed performer of these songs.” The three songs they recorded for Pathé Records were from this volume; these songs were also the most-performed music in their lecture-recitals.

Lullaby sang Jana, ay, ay, / To Bula’s baby sweet, ay, ay!

But in her lullaby / Bitterly she cursed him.

God keep thee not oh child, ay, ay! / You Bula’s baby sweet, ay, ay!

Soon may I weep for thee, / Now I sing lullaby.

While the song is about the centuries-long Ottoman rule of the Balkans (“Bula” refers to an Ottoman woman), the plight of women around the world who are unable to care for their children due to wars and forced/migrant labor is known everywhere, and today, painfully relevant. The mother figure that Ivanka embodied on the stage was a multifaceted female role model, a strong mother character dealing with conflicting emotions and turbulent events, with love, wars and losses.

The other side of the recording features two exuberant love songs, and this contrast caused me to overhaul my research. Together with archival findings that show Ivanka as a feminist, they portray Ivanka as a Yugoslav “New Woman” – one who could sing lullabies as well as the sensual and passionate love songs; furthermore, one whose role went beyond the concert stage. She was an active partner in choosing ‘folk’ material for her husband’s songs. She made an imprint in Miloje’s songs, influencing his recitative phrases with delicate dynamics, his choice of (her) tessitura, his detailed articulation markings, and his penchant for poems about nature and maternal songs. All of these suggest that she was no mere “megaphone” for her husband’s work, but rather a performer who commanded an authorial voice.

I have woven the material thread I found in Ivanka and Miloje Milojević’s songs in my subsequent performances of this repertory, creating a song cycle depicting different stages of a woman’s life. Among Miloje’s early songs are “Nimfa” (The Nymph) and “Hercegovačka uspavanka” (The Lullaby from Herzegovina), delicate and soothing, composed for his wife during their studies in Munich.

The songs Milojević composed during World War One brought different sentiment. They feature lullabies and prayers of mothers waiting for the loved ones to return from the battles, culminating with “Zvona” (The Bells), a cry of a mother burying her child.

While the national discourse in the region descended from the unifying Yugoslav tendencies in the first two decades of the twentieth century through the disintegration of the 1990s, the songs are no less relevant today. As expressions of the motherly love, but also the pain of mothers who lose their children crossing ethnic, national and religious boundaries, these songs remain universal.

[See Verica Grmusa’s previous post.]

Acknowledgments

A big thank you to Mina Miletić. I am grateful for all of the years we have made music together.

I write on how embodied knowledge gained in performance informed and guided my historical research, and changed and modelled my subsequent performances, in: Verica Grmuša: “An Autoethnographic Approach to Linking Performance Practice Research, and Historical Research,” in Peter Gouzouasis and Christopher Wiley (eds.), The Routledge Companion to Autoethnography and Self-Reflexivity in Music Studies (London and New York: Routledge, 2021).