The American women in peace organizations active between the two World Wars wanted more than political agreements between the nations of the world. They sought to transform the culture that glorified war. To that end, they set out to educate children and influence adults by any means possible, including music. Yet standard song books only contained war songs, designed to rouse emotions and create future soldiers. What was needed was new songs for peace.

The Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom (WILPF), still active, was one of several groups that circulated peace materials to be used in schools, churches, and civic programs. Their “Committee for the Encouragement of Artists, Musicians and Writers of Productions Promoting Peace,” later just the “Arts Committee,” provided lists of religious and patriotic songs for local branches’ communal singing. Not only could “The Star-Spangled Banner” or “Onward Christian Soldiers” be rewritten with improved, peace-loving lyrics, but some women took pen in hand to create new songs for the cause.

Elisabeth Johnson, head of the Arts Committee in the 1920s, envisioned that popular offerings would be more successful in changing hearts and minds. Her WILPF correspondence tells the story of her desire to contribute music for peace. “We allow art to go on weaving romance about war, and oppose dry formulas to the glamour that wins young blood,” she wrote to WILPF president Jane Addams. “…And so I pine for pageants, plays, poems, postcards, posters, songs, movies, dances, statues, stained glass, any medium that will first of all make peace seem ALIVE, and then heroic, beautiful.” Johnson had strong opinions about what peace music should be like. She was critical of some songs WILPF members sent to her, which she found “cheap” and lacking “originality or freshness.” She also complained of writers’ heavy-handedness in creating propaganda: “Here, this is a song. We must sing it because it Portrays our Principles Properly and will make Peace Popular.” Ideally, a song should make an “emotional effect,” though “without being too preachy or mechanical.” Ultimately, it was important to reach as many people as possible. Johnson asked Addams, “Why cannot we send out to masses of people brief, lively, picturesque presentations of our perspective from their viewpoint, with enough of sentiment and self-interest to make the appeal a dynamic one?”

The Peace Songs

Johnson’s first attempt at a peace song was “Hands Around the World.” She hoped to engage Geoffrey O’Hara, composer of the hit song “K-K-K-Katy,” to set her verses to music. O’Hara was willing to charge Johnson only $100 rather than his usual $500 fee, in sympathy with her cause. But she didn’t have the money, and her lyrics never acquired a melody. The first verse of “Hands Around the World” opens with the Bok Peace Prize, the 1923 contest for the best peace plan funded by Ladies’ Home Journal editor Edward Bok:

A fifty-thousand-dollar prize we none of us may win,

But here’s a song for every one and all are joining in,

“It’s time for bloody battle flags forever to be furled,

Hurrah for Hands Across the Sea and Hands Across the World.”

The second verse references the International Court of Justice, which had its first session in 1922 and which peace activists hoped could solve international disputes:

We once believed in bayonets and bombs of ev’ry sort,

But now you bet we want the world to fight it out in court,

No more shall men by millions in the hell of war be hurled,

Hurrah for Hands Across the Sea and Hands Across the World.

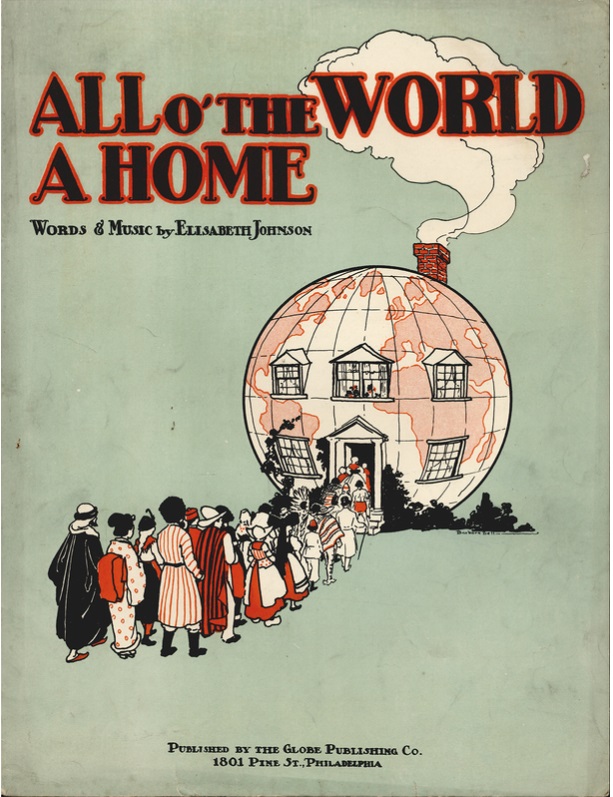

Johnson’s 1926 song, “All o’ the World a Home,” likewise emphasizes current events and international harmony. Its cover depicts people in national costumes processing into a globe-shaped house. Johnson managed to work some two dozen nationalities and ethnic groups into the song’s five verses, everyone cavorting together to a jaunty tune. A performance is available.

Today we chin with China and with far-away Japan,

With Hottentot and Eskimo and ev’ry sort of man,

A Briton is a brother and a Frenchman is a beau,

To each and ev’ry one of them, we’d like to say “Hello!”

Refrain:

We want to play in a sporty way with ev’ry one of the folks,

To give and take a brighter, gayer, jollier line of jokes!

We’re sure to win if we lend a hand, as onward in life we roam,

To make the Earth a Mother-land, and All o’ the World a Home!

The second verse mentions that the “Olympic games, we find again, their former ‘kick’ have got.” Two years earlier countries deemed responsible for WWI had again been allowed to participate in the world games, and Germany was invited back in 1925. Johnson’s final verse is less concerned with the World Court than with tennis, which “gives the world a court whose every ruling we obey.” Yet the theme of international appreciation predominates, as Americans celebrate their Irish heritage on St. Patrick’s Day, wear hats from Panama, or learn Spanish to understand their Mexican neighbors.

World War II

Johnson composed at least one more peace song, “The Song of the Unknown Soldier,” published in 1941 during World War II. In the chorus, the soldier killed in 1917 begs for “No more war!” Faced with the return of fighting, Johnson could no longer provide a purely optimistic vision of future world happiness:

Your foolish faith in armaments has proven all in vain,

They lead you to destruction, sickness, poverty, and pain;

And even to the tyranny you seek to overthrow,

For freedom by the hand of war is dealt a deadly blow.

Johnson sent a copy of her song to First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, inscribing the cover with words from its anonymous subject: “To Mrs. Roosevelt — ‘Plead with the President. He is robbing me of my peace.’” However, during the war years Americans were more likely to be listening to “Praise the Lord and Pass the Ammunition,” and women songwriters, amateur as well as professional, were far more likely to be writing songs like Ann Ronell’s 1942 hit, “The Woman Behind the Man Behind the Gun.” Nonetheless, Elisabeth Johnson’s songs reflect the desires of thousands of American women activists to end war and their hope that they could effect large-scale cultural change, creating peace through music.

Notes

Banner photo caption: American delegates, including Jane Addams (front row, second from the left), on their way to the International Congress of Women, held at The Hague in 1915. From the Library of Congress.

For an overview of the women’s peace movement, see Harriet Hyman Alonso’s Peace as a Women’s Issue: a History of the U.S. Movement for World Peace and Women’s Rights (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 1993). Johnson’s role in the WILPF is discussed in Wendy B. Sharer’s Vote and Voice: Women’s Organizations and Political Literacy, 1915–1930(Carbondale: University of Southern Illinois Press, 2007), 72–74.

“All o’ the World a Home” was recorded by Isaac Wenger with Dr. Philip C. Carli, piano, as part of Joanne Bernardi’s Re-envisioning Japan project at the University of Rochester.

Elisabeth Johnson’s letters are found in the papers of the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom, Swarthmore Peace Collection, digitized in Gale Primary Sources Women’s Studies Archive. Her copy of “The Song of the Unknown Solider,” is located in Eleanor Roosevelt’s Papers, FDR Presidential Library and Museum, Hyde Park, New York.