In 1882 in Zagreb, then part of Austro-Hungarian Empire, Maja Strozzi-Pečić was born into an artistic family. When only seventeen, she went to study singing in Vienna, making her operatic debut two years later in Wiesbaden. She moved to the Graz opera in 1903, where she met her first husband, a Russian aristocrat of Greek descent, Konstantin Papandopulo (1876-1908). They were married in 1905, and their son Boris Papandopulo, who became one of the most prolific Croatian composers of his generation, was born in Bad Honnef in Germany the following year. Strozzi-Pečić withdrew from the opera stage after getting married, in compliance with societal constrictions, and only after being widowed in 1908 did she return to opera in Graz. Unsurprisingly, life as a single mother and opera singer proved difficult, and in 1910 she returned to Zagreb to be with her family. She joined the Zagreb Opera as Rosina in 1910, where she sang until her retirement from the operatic stage, portraying, among others, Madame Butterfly, Rusalka, Lucia, Mimi, Melisande, Marguerite, Desdemona and – her signature role – Violetta.

While Strozzi-Pečić left no recordings, reviews praise her vocal and acting skills: “in Mrs. Strozzi’s performance the coloratura is in the service of music expression; we forget virtuosity because we are enchanted by art.” (“On the Performance of Lucia,” Hrvatski pokret, 15 March 1913). Thomas Mann, in his novel Doctor Faustus, described her as “My friend, Maja Strozzi, perhaps the most beautiful voice of both hemispheres” (Mann 1948: chapter 37), and, among many other composers, Igor Stravinsky dedicated his Quatre Chants Russes to her.

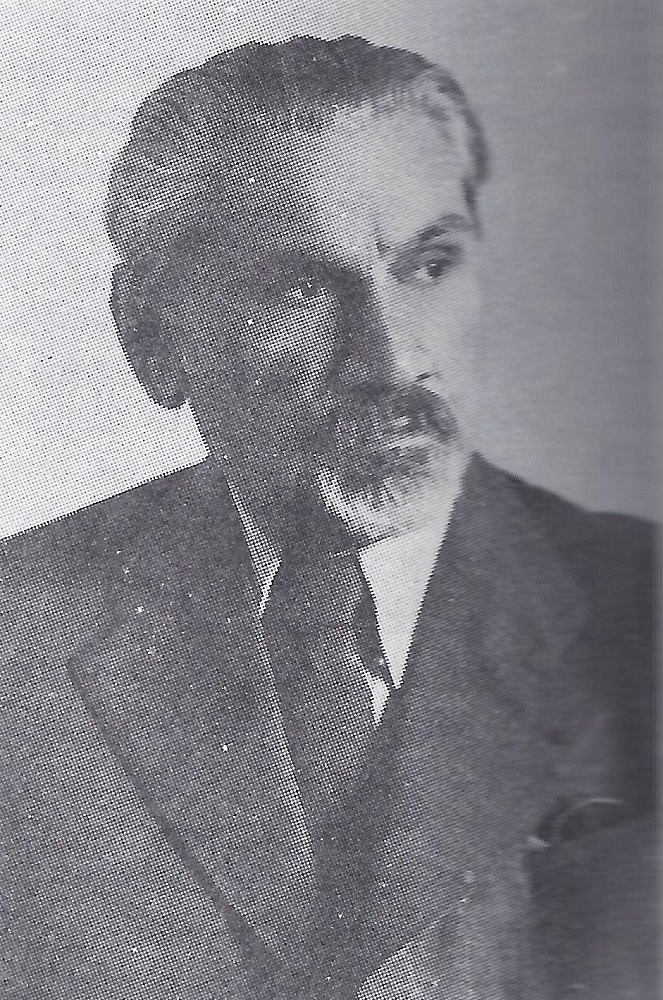

Though a celebrated opera star, Strozzi-Pečić is today better-known for championing the ‘national’ song repertory – songs composed by South Slav composers. Upon returning to Zagreb, she spent more than two decades touring the South Slav regions and Europe, premiering a vast number of works written for her by Croatian, Serbian and Slovene composers – activity matched only by that of Ivanka Milojević. Like Ivanka, who was accompanied by her composer husband Miloje Milojević, Strozzi-Pečić was accompanied exclusively by her second husband Bela Pečić (1873-1938), an excellent amateur pianist who devoted his life to facilitate his wife’s concert career. The couple collaborated with leading artists, including Stravinsky, with whom they performed his songs and piano pieces for four hands.

In contrast to Ivanka Milojević who never ventured to opera, Strozzi-Pečić reconciled her operatic career with the ‘noble’ quest for the ‘national art song. Her public voice went beyond the stage; she gave interviews and actively commissioned new works. One of her most productive collaborations was with Petar Konjović (1883-1970), the prolific Serbian composer of song and opera, who spent his early years working in Croatia. In 1916 Strozzi-Pečić commissioned a song from Konjović for her forthcoming Sarajevo concert. This proved to be a crucial moment in their collaboration. For Strozzi-Pečić, it opened a world of sevdalinka folk tradition, melismatic and virtuosic songs of love and longing, suiting her temperament and operatic skills. For Konjović, her enthusiasm for the songs resolved his dilemma about appropriating the “Oriental” elements, associated with Ottoman history and low-brow tradition, into art music.

Koštana

In a letter to a friend, Konjović wrote:

While talking about the sevdalinka style, she [Strozzi-Pečić] asked me if it would be possible to compose an opera in that style. I told them [Strozzi-Pečić and Bela Pečić] about ‘Koštana’, the one that I’ve been carrying in my heart for some time now, in hope that passionate motives from Vranje [a town in southern Serbia] could give a new Carmen. The enthusiasm she showed, and the way she understood instantly the soul of this music, with her supple voice and passionate heart, fueled my desire, and nothing will quench my angst till my dream becomes a finished work. (Mosusova, 158)

This work was to become his most famous opera, Koštana (1931), based on a play by Borislav Stanković (1875-1927). Koštana, the main character, is a beautiful, young and talented Roma woman, who supports her entire family with her singing but meets a tragic fate. Her beauty and music are deemed a threat by the village elders; she is expelled from the village and forced to marry an outcast.

While in this opera Konjović followed Leoš Janáček, both in his treatment of the ‘folk’ material and the recitative vocal lines, Koštana’s songs stand out. Koštana’s music, modelled on and inspired by Strozzi-Pečić, is sensual and erotic, melismatic, flowing, playful, seductive and full of longing. Here, the young woman entertains guests with a folk song comparing female beauty to a river that cannot be bridged: neither strangers nor relatives can resist her charm.

Such is Koštana’s rendition of a song about a woman who betrays her husband, that at the end the enchanted villagers exclaim: “It is as if the devil himself was in her.”

The realization of the opera took longer than expected, and by 1931 when it premiered, Strozzi-Pečić was no longer actively performing on an operatic stage. Nevertheless, she championed the songs that inspired it, giving the opera a “prequel” on the concert stage. Bold and virtuosic, Maja Strozzi-Pečić voiced and embodied a different model of femininity to that of Ivanka Milojević; instead of the mother-characters, she sang sensual, passionate, erotic songs of love and longing. Though she had been described as singing with “hot theatrical blood that she inherited from her mother” – the actress Marija Ružička-Strozzi, the “Croatian Sarah Bernhardt” (Konjović, 1920, 109) – her enduring legacy is that as the “apostle of national song” (Obzor, 6 March 1917).

Bibliography

I am particularly fond of these recordings as Koštana was sung by Gordana Jevtović-Minov (1947-2007), my first singing teacher in Belgrade. She sang this role both on stage in National Theatre Opera in Belgrade and on film.

For more, see:

Verica Grmuša, “An Autoethnographic Approach to Linking Performance Practice Research, and Historical Research,” in Peter Gouzouasis and Christopher Wiley (eds.), The Routledge Companion to Autoethnography and Self-Reflexivity in Music Studies (London and New York: Routledge, forthcoming 2021).

Nadežda Mosusova, “Prepiska izmedju Petra Konjovića i Tihomira Ostojića,” [Correspondence between Petar Konjović ans Tihomir Ostojić.] Zbornik Matice srpske za književnost i umetnost 19/1 (1971): 153-169.

Risto Peka Pennanen, “Melancholic Airs of the Orient –Bosnian Sevdalinka Music as an Orientalist and National Symbol,” Collegium: Studies across Disciplines in the Humanities and Social Sciences 9 (2010): 76-90.