Stories that begin with a mother dying in childbirth or succumbing soon after, leaving a father and child to fend for themselves, have a heritage that reaches back centuries. Many films (Sleepless in Seattle is one) begin with this plot device, as do a shockingly large number of films for children, including Kung Fu Panda 2 and Ice Age. Disney’s animated films have depended on this conceit for generations: Bambi, Cinderella, Snow White, Beauty and the Beast, Fox and the Hound, Brother Bear, Ratatouille, and Little Mermaid 3. Typical is Finding Nemo (2003), which commences with a barracuda devouring Nemo’s mother (Boxer). Novels, plays, myths, and fairy tales have examples of dead or absent mothers, from Shakespeare’s The Tempest and King Lear, to Dickens’ Bleak House (in which ‘Nemo’ is a character), to Jane Smiley’s Pulitzer-Prize-winning A Thousand Acres. The absence of a mother was until recently “so normative as to go unnoticed” (Dever, 22).

Among popular songs, there were many in the 1890s and early 20th century, such as Gussie L. Davis’s “In the Baggage Coach Ahead” (1896) about a father cradling his crying baby, the body of his wife “dead in the coach ahead,” or Charles K. Harris’s evergreen tear-jerker “Hello Central, Give Me Heaven” (1901), about a young girl trying to call her dead mother. None is more direct than the spiritual, “Sometimes I Feel Like a Motherless Chile.” And opera plots have long exploited this archetypal theme, either having the mother die in childbirth (Debussy’s Pelleas et Melisande), or more often fashioning a female lead who had long ago lost her mother (Wagner’s Flying Dutchman, Verdi’s Rigoletto, Umberto Giordano’s Andrea Chénier).

This is part of the context for one of Carrie Jacobs-Bond’s most successful songs, “His Lullaby,” from 1907. Setting a poem about a father comforting his motherless baby, Bond composed “His Lullaby” expressly for Ernestine Schumann-Heink, then the pre-eminent contralto in the United States and Europe, a fixture at the Bayreuth Festival, and the singer for whom Strauss created the roll of Klytaemnestra in Elektra. The sentimental poem by Robert Emmett Healy had only recently appeared in Good Housekeeping in August, 1906, and shortly after spread in newspapers around the country. Bond evidently composed her song in the following spring or summer, because she copyrighted it, as one of Two Songs for Contralto, on 4 Sept. 1907. Healy made a name for himself, but not as a poet. An attorney, he became a judge, and briefly in 1914-15 an Associate Justice of the Vermont Supreme Court. From 1928-34 he was chief counsel for the Federal Trade Commission, before serving three terms as chairman of the Securities and Exchange Commission during the turbulent years 1934-1946. As she often did, Bond altered the original poem. I’ve marked these changes in italics and provided the original words immediately after. Healy subsequently published his poem, incorporating all of Bond’s revisions.

His Lullaby

You cried in your sleep for your mother dear,

Baby, Baby.

I would you could call her back to us here,

Baby, Baby.

The little lambs are asleep on the sod,

And my own lambkin’s beginning to nod,

And over [orig: back of] the starlight your mother’s [orig: mama’s] with God,

Baby, Baby [orig: Baby, baby, baby].

Sleep has come to the birds with the dew,

Baby, Baby.

Her eyes were as blue as the eyes of you,

Baby, Baby.

Dreams for your slumbers come up from the deep,

I’ll love as she loved [orig: hold as she held you] till morning lights peep,

And mother above us [orig: mama in heaven] will watch while we sleep,

Baby, Baby [orig: Baby, baby, baby].

“His Lullaby” was the pinnacle of Jacobs-Bond’s many years of composing lullabies, the eighth of at least eleven. One of her first two publications was “Mother’s Cradle Song” (1895), on a poem she likely wrote herself (it is uncredited each of the three times she published it). Aside from the presence of a mother who was actually alive, this poem anticipates “His Lullaby” most strongly in its assurances that the vigilant “mama will protect you from harm” and will “watch while you rest.” She followed this in 1897 with “Come Mr. Dream-Maker,” and 1899 with “The Bird Song,” another lullaby that is as much about the parent as the child. For a time these three early songs comprised a regular set in her recitals. She also wrote songs about the act of singing a child to sleep, from 1901 “Des Hold My Hands Tonight” and Paul Laurence Dunbar’s “Po’ Lil’ Lamb,” both for years a popular part of her entertainments, and “A Bad Dream,” and “I Was Dreaming – Maybe” (1902). After “His Lullaby” came “Hush-a-by” (1911), and then “A Sleepy Song” and “The Sandman” (both from 1912). To judge from the number of times these songs appeared on recitals across the country, they sold well. Still, none approached the acclaim awarded “His Lullaby.”

Schumann-Heink made “His Lullaby” a regular, and culminating, part of her recital program for most of her American touring career, from late 1907 into 1923. She recorded it with orchestra on 28 Jan. 1908 for the Victor Red Seal label (#88118). Victor issued it in late April and continued to market it, also into 1923. It was possibly the very first recording (as opposed to piano rolls) of a song by Bond. Of the seven disks of “His Lullaby” issued between 1908 and 1922, all were sung by women, even though the voice in the poem is the father’s. Among many accounts of Schumann-Heink performing this song, these indicate the affective power she wielded, largely because of the emotional impact of her voice:

1907, 16 Oct., York [PA] Dispatch – … then the prima-donna sang her most touching English selection, “His Lullaby,” written for her by Carrie Jacobs-Bond. Her audience scarcely breathed as her rich clear voice portrayed all the grief of a bereaved father consoling his child over the loss of the one they both loved most. So remarkably was the artist’s power of expression revealed here that her voice as it crooned through the soothing melody seemed actually sob-laden, and the eyes of many of those in the audience were filled with tears.

1908, 7 Feb., Pittsburgh Press – … it is said the tender pathos of this song as sung by the great diva has never failed to touch her hearers to the point where tears flowed without restraint.…

1909, 28 Jan., Riverside [CA] Daily Press – as Mme. Schumann-Heink says, “let me sing you Mrs. Bond’s ‘Lullaby’ and you will never want to hear any other.”

1910, 14 Feb., San Francisco Call – Many handkerchiefs were waved when she sang Carrie Jacobs-Bond’s “His Lullaby.” The tenderness of the simple song was turned into something sacred, and the handkerchiefs were not waved to cheer, but to tears.

1910, 3 Dec., Newark Star-Eagle – Newark today still softly hums the closing strains of “His Lullaby,” with which Mme. Ernestine Schumann-Heink ended the program […] last evening. Just as the concert was the greatest artistic success Newark has ever seen, so also was the diva’s rendition of the pathetic, wailing words of the lullaby a dramatic triumph. She sang her way straight into the hearts of a city, and as the last words left her lips, the audience, numbering 1,700 men and women, with scarcely a dry eye among the whole number, united in one vast sigh, which was general from orchestra to gallery.

Schumann-Heink’s 1908 disk offers us only a faint glimpse of the magnificent voice that moved people to communal tears and sighs. To our ears the low fidelity and the surface noise obscure the essence of her artistry. We hear across the decades dimly. Yet elements of her interpretation can still be appreciated: the deliberate tempo, her rubato, the richness of her lower register, her ability to be gentle in her upper register, and the way she slides, arriving at the destination note in advance of the actual beat. The best reproduction of her recording is available on this page. There is also Lucy Isabelle Marsh’s performance from 1913:

Audiences responded and other composers took note. Charles Wakefield Cadman set “His Lullaby” in 1908, and Amy Beach published her Two Mother Songs, op. 69, in 1909, with the lullaby “Hush, Baby Dear.”

But even if it were possible to bring Schumann-Heink back to sing “her” lullaby today, this song, however beautiful, however moving some may still find it, will likely not leave entire theaters in tears. A century ago fears that a mother would die during or soon after childbirth were real; maternal mortality rates were unimaginably higher than they are today. A rise in the standard of living in the 1890s meant that overall mortality, including infant mortality, started to decline in that decade; and yet, maternal mortality rates remained consistently high from the middle of the 19th century to the mid-1930s (Loudon, 241S-43S). Moreover, many more mothers died in childbirth in the United States than in England, Wales, and Northern Europe. In the early 20th century, twenty countries kept track of maternal deaths. The U.S. ranked 19th, with rates twice as high as Denmark, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands and Sweden. In 1930 there were approximately 700 deaths per 100,000 births in the United States as opposed to 250 deaths in the Netherlands (Loudon, 243S). This compares to 17.4 maternal deaths per 100,000 births in the U.S in 2018, a number that has risen in the years since COVID. Thanks to Roe v. Wade being overturned and the passage of new laws restricting women’s access to adequate health care, maternal deaths are predicted to rise by as much as 21%, according to recent studies.

The poignant scene depicted in Healy’s poem doesn’t carry the same emotional weight now as it did then. How could it? However long-lived the cultural context of fables about a lone father raising a child might be, a century ago the context that mattered for those who read Healy’s poem or listened to a performance of Mrs. Bond’s song was the social awareness of how life-threatening childbirth could be. “His Lullaby” is less a lullaby than the expression of a father’s grief and a society’s deep anxiety. Again and again, year after year, Schumann-Heink used it to bring her audiences a few healing moments of communal catharsis.

Notes

There is much of interest on Ernestine Schumann-Heink in Laura Tunbridge, Singing in the Age of Anxiety: Lieder Performances in New York and London Between the World Wars (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2018).

The poem by Robert Healy first appeared in Good Housekeeping 43/2 (Aug. 1906): 150. Among newspapers that then reprinted it are the De Kalb [IL] Chronicle, 20 Aug. 1906, and the Des Moines Register, 16 Sept. 1906.

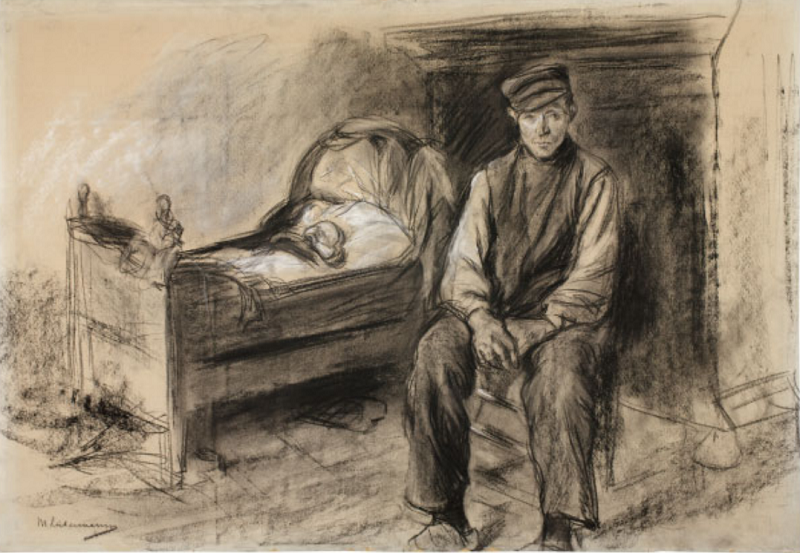

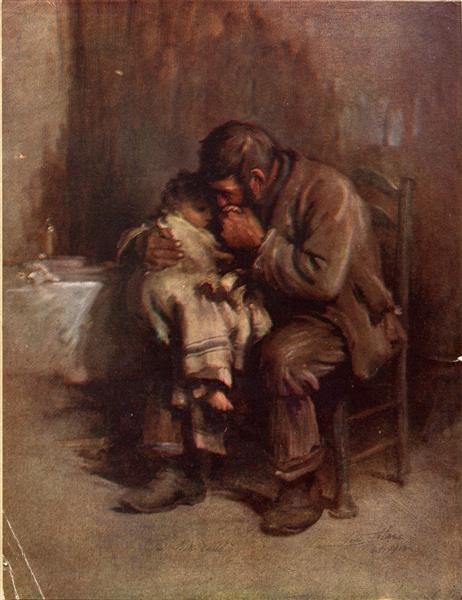

Other paintings of widowers with one or more children are Thomas Faed, The Mitherless Bairn (1855), Otto Edmund Günther, Der Witwer (The Widower) (1874), Luke Fildes, The Widower (1875), James Tissot, The Widower (1876), Arthur Stocks, Motherless (1883), Robert Sanderson, The Motherless Bairn (1895), and Edvard Munch, The Dead Mother and Child (1897-99).

Sarah Boxer, “Why Are All Cartoon Mothers Dead?” Atlantic Magazine 313/6 (July-Aug. 2014): 96ff.

Carolyn Dever, Death and the Mother from Dickens to Freud: Victorian Fiction and the Anxiety of Origins (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998).

Terri Sabatos, “Father as Mother: The Image of the Widower with Children in Victorian Art,” Gender and Fatherhood in the Nineteenth Century, ed. Trev Lynn Broughton, Helen Rogers (New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2007), 71-84.

For recent statistics on maternal death rates, which vary according to the race and the age of the mother, see this report.

Irvine Loudon, “Maternal Mortality in the Past and Its Relevance to Developing Countries Today,” The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 72/1, July 2000: 241S-46S

Jacqueline H. Wolf, “Saving Babies and Mothers: Pioneering Efforts to Decrease Infant and Maternal Mortality,” Silent Victories: The History and Practice of Public Health in Twentieth Century America, ed. John W. Ward, Christian Warren (New York, Oxford University Press, 2006), 135-60.

Tamara Estes Savage, “Maternal Mortality and the Progressive Era: A Critical Examination of the Past to Inform the Present,” Open Journal of Social Sciences 8 (2020): 193-206.